We’ll state right up front that flying IFR these days without even a portable GPS is just foolish. No matter how good your VOR skills might be, if you get that kind of situational awareness and backup in a used GPS for the cost of two tanks of avgas in a Cessna 172, why wouldn’t you fly with one?

That said, neither our GPS-and-WAAS satellite constellation, nor a $16,000 IFR-GPS navigator, is bulletproof. And even when you happily supplement your /U or /A status with a portable GPS, batteries die, screens fail and sometimes it’s easier to employ a few knob-twisting tricks rather than struggle to input the name of an unanticipated fix while trying to keep it all upright in turbulence.

So (maybe for the last time in the run of this magazine) here are some of those VOR tips and techniques you may have forgotten. You never know when they might come in handy.

No HSI Here

The beauty of an HSI is that it gives you a top-down representation of where the aircraft is relative to the selected course. The downside is that the thing costs a bundle to install and repair, so it’s not a common feature in traditional, light-GA, six packs.

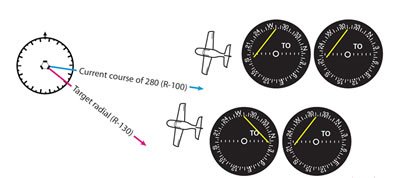

You can do the same trick in your head if you mentally superimpose the aircraft symbol from your heading indicator onto the OBS compass rose with the nose of the airplane symbol pointing to your current heading. Double-check that your heading is synced with your magnetic compass before you do this, as a bad heading will seriously complicate matters.

Step two is to make sure that heading corresponds to a number in the top half of the OBS. That is, when you superimpose the airplane symbol, it should be flying generally forward. If it is, you have what I’ll call “heading-OBS agreement,” and should have correct sensing and a correct To/From flag. If the airplane symbol is pointing backwards, then your CDI sensing and flag are also backwards—classic reverse sensing.

Assuming you don’t have reverse sensing, you now have that coveted HSI-perspective, and you can see if the aircraft is likely to intercept the course and by how much of an angle.

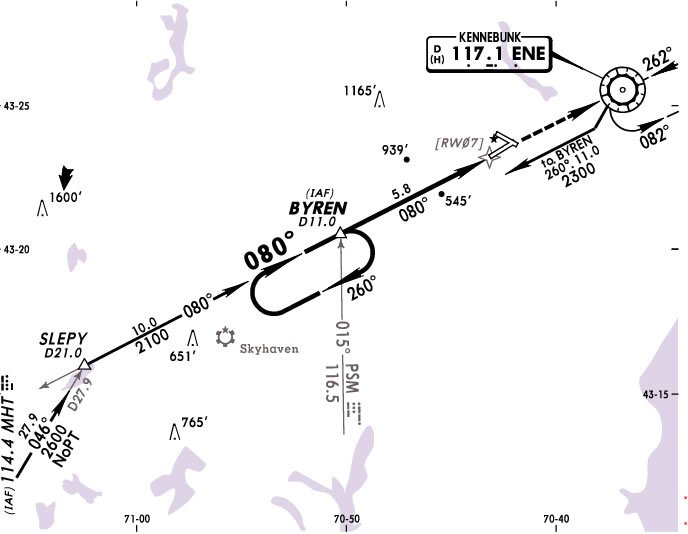

A perfect application of this is when you get an ATC instruction like “Join Victor 23 then proceed on course.” Some of the more advanced portable GPSs have victor airways, but many don’t. The nearly-ubiquitous Garmin GNS 430 doesn’t have them, either. A quick tune of the VOR to the radial for V23 and the visual superimposition of the airplane symbol gives you the picture you need of relative position and intercept angle, even if the GPS doesn’t.

Remember this doesn’t adjust for wind. If you want to step it up to expert usage, take the actual track over the ground shown on your GPS and use that as the “heading” for the airplane symbol when you superimpose on the OBS. That’s your actual intercept angle with wind effects taken into account.

Another time this might come up is for an approach with stepdowns marked by crossing radials. Suppose you tuned the crossing radial and then got busy with cockpit tasks. You scan again and see full-scale deflection but can’t remember if that’s what you saw before—or if the needle swung and you missed it. Superimpose the airplane symbol and check for heading-OBS agreement. If the course line is ahead of the symbolic aircraft nose, you haven’t crossed yet.

A variant on this technique tells you if you’ll intercept a given radial to a VOR before you pass the station or not. Dial up the radial on Nav 1 (actually, the inverse of the radial, since you’re heading to the station) and then dial your current heading on Nav 2. Nav 2 shows your position relative to a radial parallel to your heading, which is a radial you will never cross (assuming no wind here). If that radial and your intercept show opposite fly-left/fly-right indications, you’re good. If they match, you’ll blow past the station without intercepting anything. Use your portable GPS track in lieu of heading in this technique and you’ll have wind correction as well.

Direct Without RNAV

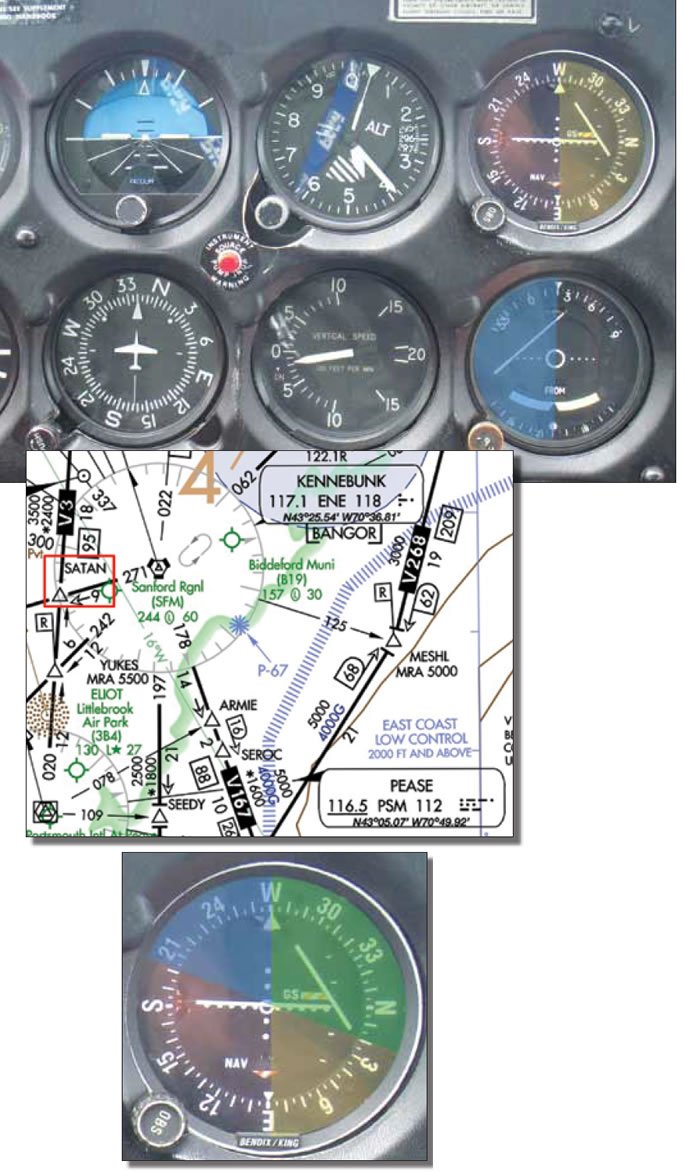

Direct to any intersection is a wonderful GPS trick—except you don’t need GPS to do it. What you need is a way to get going in the right general direction and a way to “trap” and course errors, so you won’t miss the intersection entirely.

Step one is to dial the two radials that define the fix. Now look at the OBS/CDI for Nav 1. The half of the OBS on the same side as the CDI needle are the range of headings that could take you toward that radial. For example, if you have R-270 dialed in the OBS and the needle is fly left—that is, it’s deflected next to the 180 mark on the OBS compass rose—then the heading you want is somewhere to the south between 090 and 270.

Do the same for Nav 2. Suppose that was the 360 radial and you had a fly left indication (CDI needle parked near 270). That means the heading you want is also somewhere to your west between a heading of 180 and 360.

Since both of these cases must be true for the heading to the fix, you can combine them by superimposing one range of possible headings on the other. The only remaining possibilities are where they overlap: a southwest heading somewhere between 180 and 270 in this case.

In a pinch, you could just fly southwest (assuming ATC approval and adequate off-route terrain clearance) and you’d be going generally the right way. Applying a bias to that for your estimated position and winds is even better. You’ll almost certainly hit one of the two radials first, but you can track it until the other CDI centers. This technique is best when combined with a corroborating vector from ATC or heading from your portable GPS.

It’s a totally-legal direct-to without an IFR GPS for those who need it (you know, like Eclipse 500 pilots). It can also be used to go relatively direct to any position you can define by two crossing radials. Getting over an airport in an emergency when all you have is two VORs comes to mind. If you get a zone-of-ambiguity reading for one VOR, you’re at a 90-degree position to that course. Set a 45-degree intercept until you get past that position, and then refigure.

Ain’t Dead, Yet

The VOR system will, eventually, go the way of restaurant smoking sections. But that’s still years off. Until our NextGen nirvana arrives, it’s worth keeping up at least basic competency with the elder equipment still in our cockpits.

Besides, it’s fun to peer into the crystal ball of multiple compass roses and cryptic needles to extract a navigation solution that actually works. Any poor sap can read a moving map.

As he feels more and more like a museum piece himself, Jeff Van West’s Luddite streak gets stronger.