It was a pleasant evening. Four miles from my tower cab, an air-ambulance helicopter was speeding back to his hospital with a critical patient on board. I saw his nav lights in the distance.

Suddenly, his radio clicked, followed by a surprised, “What the—?” I sat up in my chair. He keyed up again. “Hey, Tower, we just got hit by a laser. We’re maneuvering.” I didn’t have any traffic in the vicinity and told him to maneuver as necessary, then asked if he needed assistance. “My night vision’s shot,” he replied, frustration seeping into his normally professional tone, “but we’re good.”

Some idiot had nearly blinded that helicopter pilot and threatened the lives of his crew and patient. Here is where the controller job description goes beyond vectors and clearances. We play middle man, maintaining vigilance, identifying and distributing information on flight hazards so pilots can take action and mitigate risk. Most of the time, it’s standard weather, NOTAMs, and traffic.

However, when we encounter dangerous situations like this—where there is a direct, immediate threat to flight safety beyond the explicit control of the controllers or pilots involved—we must do two things: ensure everyone affected gets informed, and tell someone who can do something about it.

Seeing Green

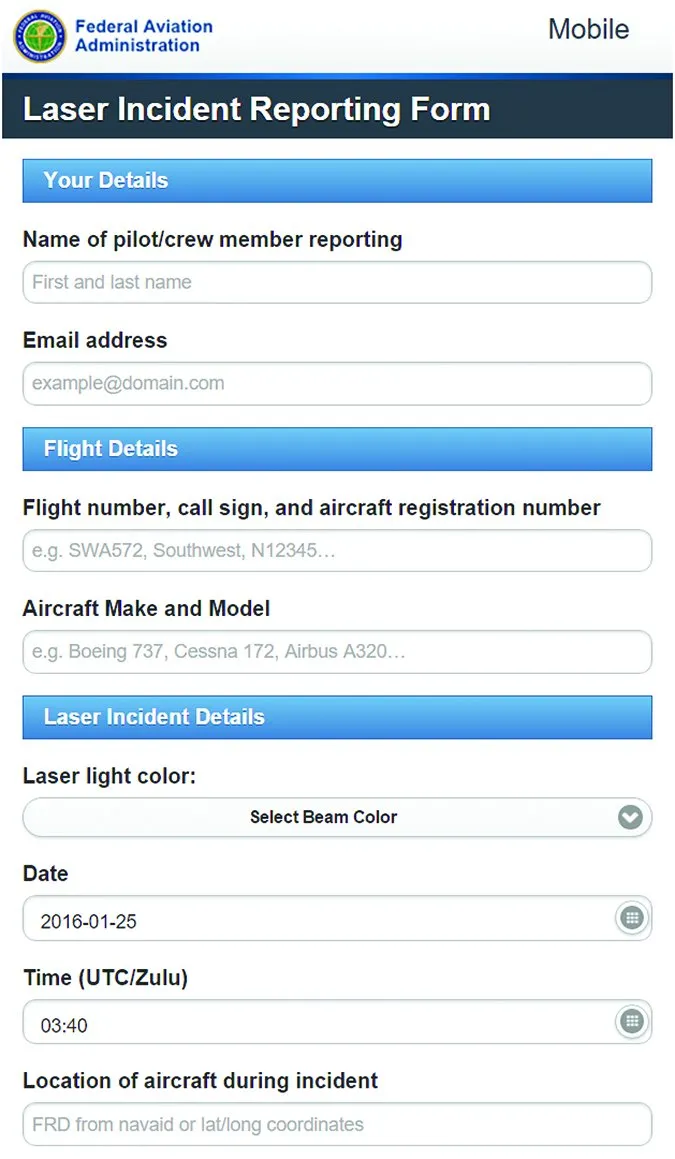

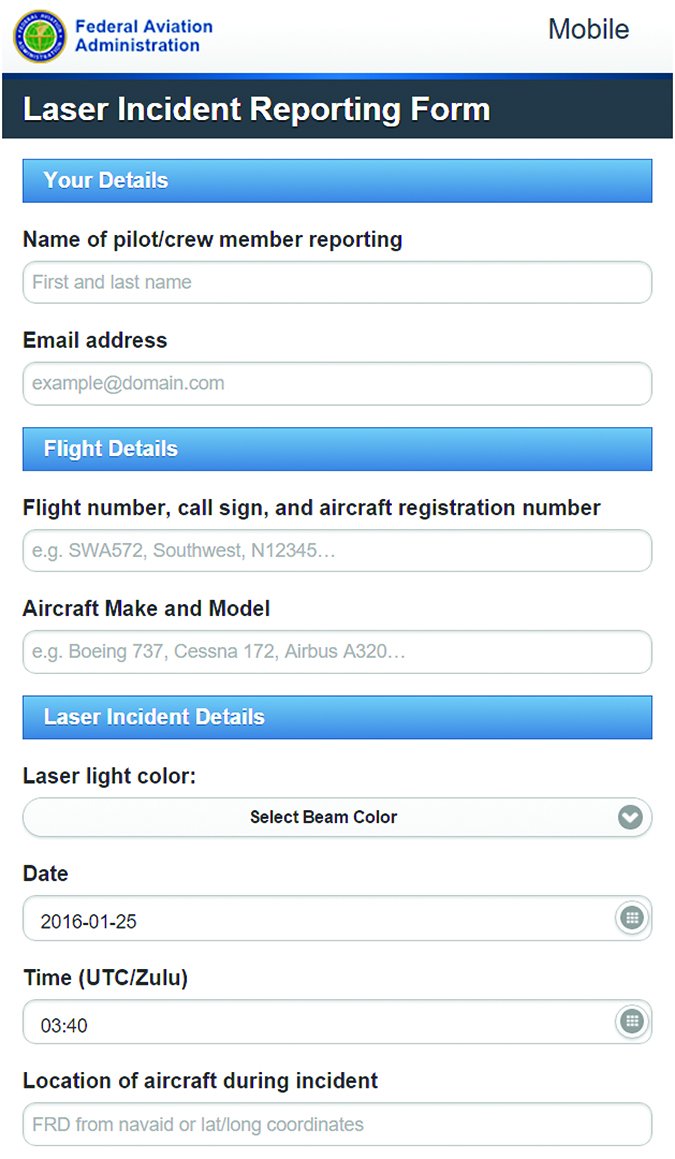

As a pilot you most certainly know that just about everything in aviation has a checklist. We controllers have our own checklists for a multitude of hazardous situations, unauthorized laser illumination included. I pulled up the appropriate checklist while the helo maneuvered.

The first thing listed was warning anyone else in the vicinity. Per FAA Order 7110.65 10-2-14, “When a laser event is reported to an air traffic facility, broadcast on all appropriate frequencies a general caution warning every five minutes for 20 minutes following the last report.” We also need to include it on the ATIS for an hour after the incident. “Include the time, location, altitude, color, and direction of the laser as reported by the pilot.”

Once the helicopter had resumed normal flight, I asked him for details. I then recorded a new ATIS with the following message: “Unauthorized laser illumination event, at 2300Z, 4 miles north of the airport at 1500 feet, green laser from the west.” I then broadcast the information on my standard frequencies and advised my buddies in Approach. I would also have to fill out a Mandatory Occurrence Report for our records.

However, the paperwork could wait. Just warning other aircraft and controllers wasn’t enough. The priority was finding whoever was responsible for the incident. Laser-illuminating an aircraft is a federal offense that endangers both whoever’s aboard, and—in the event of a resulting crash—people and property on the ground. Per 18 U.S. Code 39A: “Whoever knowingly aims the beam of a laser pointer at an aircraft in the special aircraft jurisdiction of the United States, or at the flight path of such an aircraft, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than 5 years, or both.”

As the helicopter landed safely, I grabbed the phone. The first recipient on the list? Local law enforcement. With our procedures, we have to call our airport management with the details and they’ll call the police. Other facilities may call law enforcement directly. Either way, the cops get told where to look, and hopefully they’ll track down the perpetrator.

The next call? The Domestic Events Network (DEN). Created after the 9/11 attacks, it’s a 24/7 FAA hotline including all Air Traffic Centers and various government agencies throughout the United States. Its purpose is “to provide timely notification to the appropriate authority that there is an emerging air-related problem or incident.” These are serious, no-nonsense people who track incidents throughout the country.

Not the Brightest Bulbs

Thanks to information provided by pilots and ATC, law enforcement has made arrests in a number of cases. A quick perusal of the sentencing records on LaserPointerSafety.com indicates many perpetrators really know how to pick the wrong target. Popular ones included Sheriff’s Department, Homeland Security, and public safety helicopters, often equipped with infrared or low-light cameras that easily found the laser’s source.

Many of those individuals arrested were just bored or drunk, or simply trying to see how far their laser would shine. In November 2015, a New York cook was arrested for shining a laser at two news helicopters—who caught him on camera—because “he thought it was funny.” While these folks deliberately aimed their lasers at aircraft, many simply weren’t aware of the threat they were posing. Their ignorance cost many of them greatly in fines and prison time.

Of course, not all laser events are intentional. For example, over the holidays, I saw some homeowners setting up laser projectors casting a field of stars or patterns over their houses. While most pointed them at a wall or fence, some were placed underneath trees, shooting straight up. It illuminated the tree, yes, but every beam that didn’t hit a branch or leaf was lasing nothing but sky—or an unsuspecting aircraft that happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Those lasers can reach a lot further than people think. This past December, an American Airlines Boeing 737 was lased at 13,000 feet, on its descent into the Dallas-Fort Worth, TX airport. A police helicopter tracked it down to a holiday light display in a home 22 miles west of the airport.

One evening, I had a Cessna practicing some night touch and goes. On one downwind pass, he reported, “Hey, I think someone just lased us.” I asked him for more detail as I went through my checklist. Apparently, one of the residents bordering the airport property was having a big party and set up a backyard light show—one of those automated devices with colored lights and, apparently, lasers that move in time with music.

In those unintentional instances, the authorities would likely start by simply asking the offending party to shut down the lasers, or point them in a safe direction. If they persist, then the charges come out.

Bees Swarming

Lasers aren’t the only growing threat out there. Unmanned Aircraft Systems—commonly called drones—are everywhere. I can walk into seemingly any store and pick a UAS off the shelf. Every day they’re getting more capable, with increased flight duration and payloads, including high-definition camera systems for aerial cinematography. However, to quote Marvel Comics genius Stan Lee, “With great power comes great responsibility.”

In November 2014, the National Transportation Safety Board ruled that UAS meet the legal definition of “aircraft.” The FAA can therefore take enforcement action against anyone who operates them in a reckless manner, and requires all UAS between 0.55 and 55 pounds to be registered. The FAA’s got a comprehensive FAQ here.

Just speaking from an ATC standpoint, these tiny aircraft can endanger aviation safety when operated carelessly in the vicinity of other aircraft. First off, they’re hard to spot. We’re not talking about massive military MQ-9 Reaper drones the size of a corporate jet. Even on the heavier end of the weight range—55 pounds—these UAS would be difficult to see and avoid in flight.

To keep them separate from manned aircraft, per the regs, UAS are supposed to remain below 400 feet, in sight of the operator, and not fly within five miles of an airport without notifying ATC. The reality is that operators are busting those rules left and right. In July 2015, a Palo Alto, CA Cessna 172 training flight had to take evasive action around a UAS at 1200 feet. That same month, a Jet Blue A320 passed a drone at 550 feet on a 2 mile final into La Guardia airport. One month prior, a Delta Airlines MD-88 reported a six-foot wide UAS at 9000 feet over Atlanta. That’s right… 9000 feet!

A Bard College report detailed 927 UAS-related incidents between December 2013 and September 2015. Of those, 327—over a third—were flagged as a proximity danger. In April 2015, the first-ever reported drone strike occurred near California’s Livermore airport. Another was being investigated in Chicago in September 2015. Thankfully, no major damage or injury was reported in either incident.

If you see a UAS, advise ATC. Even if the drone doesn’t affect your flight, it could ruin someone else’s day. UAS reports are handled similarly to laser incidents, with law enforcement getting involved to locate the operator. To aid the investigation, the controller will need whatever details you can offer, such as the aircraft’s shape, color, location, altitude, direction of flight, and type (such as a rotary or winged design). A little bit of info can go a long way to ensuring safety.

Verdicts

So, you’re probably wondering what happened to those involved in all of these drone, laser, and balloon (see sidebar) incidents? I wish I knew. That’s the problem being a middle man. We often don’t know the outcome, since we’re neither a plaintiff nor defendant in these cases. We’re just witnesses providing information that was, in turn, given to us by pilots.

The authorities act on that data, track down the offending party, and decide the level of punishment (if any). Cases can take weeks, months, or even years to get resolved. And the more reckless the action, the greater the likelihood is that serious consequences will result. If it was something significant, it can result in procedure changes to better handle a potential similar event, and we might get a briefing on those changes. Most often, though, we find out the results on the news, just like the rest of the world.

While there’s a natural curiosity over the outcome, my coworkers and I aren’t trying to get anyone in trouble. But, if someone’s intentionally or inadvertently endangering flight safety, it’s ATC’s job to get the issue resolved using the resources available. Without you and other pilots speaking up, we often wouldn’t know there was a problem at all. When you encounter the unexpected up in the sky, keep us informed.

Tarrance Kramer prefers quiet nights without blinded pilots, lengthy phone calls, and piles of paperwork.