I am tired of the rant: These technologically advanced cockpits—these GPS toys—are making us lazy idiots, slave to the magenta line. Next comes the “back in the day” bit about how we used to fly full-procedure NDB approaches in the rain with quartering tailwinds—both ways. If these computer kids would just turn off those screens and fly VOR needles and a mental map, they’d be such better pilots.

Gimme a break. That’s like saying nobody drives a stick any more, so we ought to manually shift our automatic transmissions to be better drivers. Given that in some cases now the only possible navigation is by GPS, it’s like saying manual shifting would make better Prius drivers when they don’t even have 3, 2, and L to select.

Good Old Days? Not.

First off, let’s dispel a myth with a thought experiment. You’re flying along in 1975, proceeding VOR to VOR with a good estimate to your next fix—and notice oil pressure is 15 PSI. Now you scan the chart around your position, find the nearest airport in green ink is behind you, turn roughly in that direction, ask ATC for a vector to the best approach there and for the latest weather. You then fumble in your book for a chart, find out that airport only has a VOR-A approach just as ATC says it’s below minimums. They suggest a new heading…

OK, now you’re behind modern avionics following a magenta line. An oil pressure warning light flashes. After losing several seconds because you were thinking about the Mets game (Seconds! Oh, horrors.) you punch nearest and scan the top three airports, see the second one reports MVFR, has an ILS, and is a bearing of 324 degrees. You’re on your way before even declaring the emergency. Next the chart is up for you to review.

Who had better situational awareness (SA) for this emergency? Even a distracted Mets fan can leap to the head of the line on SA if they understand their equipment and use it well.

Like any good rant, there is a nugget of truth: While GPS isn’t the death of SA, the secure, comfortable feeling you get from a moving map and an autopilot can erode your engagement. When we had to maintain a picture of our positions in our heads, the consequences of lost SA were significant. You could get off course or overshoot a turn without seeing it immediately. It could take several minutes to find yourself again, unless ATC saw it first. Now regaining SA requires about a second of looking at a screen, so there’s less natural motivation (read: fear) to stay engaged at all times.

Turning off your MFD and killing GPS position on your iPad will force a certain kind of engagement, and makes for a fun academic exercise. Yet it does almost nothing to change your regular flying regimen.

There is a better way.

Systems for Smarter

When people haul out tales of accidents or ASRS reports fueled by lack of SA, it’s usually not during an emergency. Adrenaline has a certain focusing effect on the mind. The breakdown happens during a simple departure, the mundane drone of cruise, or a routine approach. So the question is, “How do you stay engaged when everything is monotonously normal, but trouble might be brewing that you could stave off if you caught it in time?”

The techniques you find motivational may not be the same as mine. However, here are a few engagement-enhancing techniques that work for me, and I’ve seen work for others.

Sniff Test Everything

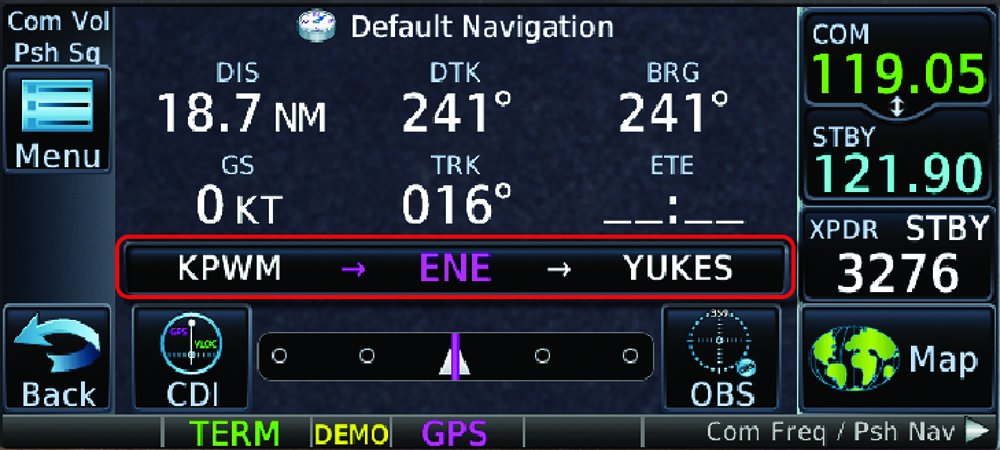

It’s simple to load a route, sometimes with the box decoding victor airways, and then move on. It takes only seconds to quickly scroll through and verify that it looks reasonable. The gain is two-fold. It both protects against the unlikely event of a mis-entered waypoint, and it’s like a quick pre-fly of your route.

It gets the whole picture in your head. If you have an iPad, all the better to quickly compare the shape of both routes on the map. They should match.

The same is true for pilot-nav departures or approaches. Load it and then scroll the waypoints to ensure they match the chart. You might have loaded the wrong one, or maybe one is out of date. Even if all is well, the act puts the waypoints in your mind. Make this part of your briefing.

Hand-fly the Boring Parts

Autopilots are great. While it’s a truism that you should be able to hand-fly approaches in case George takes a holiday, the autopilot flies a safer approach to minimums than most technically “current” (as opposed to “proficient”) GA pilots.

So, let George fly the tough approaches, but hand fly cruise, and even routine departures and arrivals to stay engaged and maintain your hand-flying skills when the stakes aren’t so high.

Of course, cruise is where we like to kick back and let the autopilot fly while we fiddle with our play lists. Instead, turn George off when things get easy. Hand-flying requires a pervasive awareness of the flight instruments while attending to other tasks. It forces engagement that may be lacking under routine autopilot operations. However, most of us remain well engaged during high-load, high-stress procedures, even using the autopilot.

Perhaps you’re asking, “What’s the difference between turning off the autopilot and turning off the moving map? You’re disabling technology to stay engaged.”

The difference is engagement in your normal system of flight. Just like turning off cruise control in the car when driving in the snow, hand flying while using all the toys puts you more in tune with your normal flight routines, without artificially limiting what you see or do. Turn it back on if you need to focus completely on something else for a while.

If nothing else, when the autopilot is flying, keep the heading bug synced up and monitor the wind vector for a continuing picture of the condition of the air in which you fly.

Hone Your Accuracy

While hand flying, see how precisely you can fly. Back in the day of flying a KLN 94 GPS coupled with a KAP 140 autopilot, one of my pre-takeoff items was to change the full-scale CDI sensitivity from 5 NM to 1 NM. The autopilot flew better, and it turned out so did I. Most GPS units have this option. For fun, sometimes I’d crank full scale down to 0.3 NM, so I had to fly enroute with approach sensitivity. Try it. It’s fun, and you do stay a lot more engaged.

You can’t fly with that kind of precision off a map, so you must use the CDI or GPS data. Make sure you see your track, desired track and cross-track error (XTE). The last one is how far laterally you’re off course. Even if you don’t mess with the CDI sensitivity, you can keep checking back to XTE and strive for accuracy to the second decimal place.

Make Fix-Crossing Reports

Back in the day just using VORs, even if you achieved the perfect Zen of scan and needle bracketing, you could only zone out until the next turn or change-over point. You were forced to remain engaged.

When the airplane does it all automatically, you can snooze until ATC wakes you up to contact the next sector. Stay engaged by making a little fix-crossing report to yourself. That’s really what all these “magenta-line” naysayers are talking about.

Every time you cross a fix, do a flow check through the airplane. Fuel and engine controls where you want them? Gauges all still in the green? Fuel and ETA at destination, and in-flight winds still what you expect? Instruments all reporting reasonable data? What’s the next fix and ETA? Finally, how’s your destination weather? Has it changed?

To sum it up, that flow is “systems, times, destination data.” If all’s well, you’re done. If something is anomalous, you investigate further. Either way, you cultivate useful engagement.

Here’s a tip to help make that happen: Set a flight timer to go off when you expect to cross the next fix. (Yes, you can read the time off the GPS.) The timer is just a reminder to do the self-report.

Map with Meaning

I was talking to a DE recently about common issues on checkrides. One that’s on the rise is inability to read aeronautical charts. Really? When tablets make sectional and enroute charts easier to use that ever before? All I can figure is that with so much pop-up airport data, the map underneath has become aviation-themed wallpaper.

Play a game with yourself in cruise. Pull up the AWOS from airports along your route just from the enroute chart—don’t use the GPS nearest function. Read off the altitude and estimate if it’s in gliding range for landing. What’s the runway length?

Too often we know our position on the map relative to, well, the edge of the map. That’s a waste. What do you show on your map? Airways? Terrain? Traffic? We’re great about where we are relative to NEXRAD returns, but often little else.

Consciously configure your screens for maximum information utility. I usually like a standard map range for an at-a-glance estimate of distance to the next fix or nearby airports. I fly approaches with a specific map zoom on the MFD because I get an intuitive feel for how long it’ll be to a waypoint visually without even needing to look at a readout.

I love airports weather conditions as color code on the tablet. It’s a quick visual on weather along and beside my route at all times. I can also see where at least some airports are at almost any zoom level.

Nothing gives as much instant SA as a map, but only if you know your place in the context of the other data.

Improve Screen Management

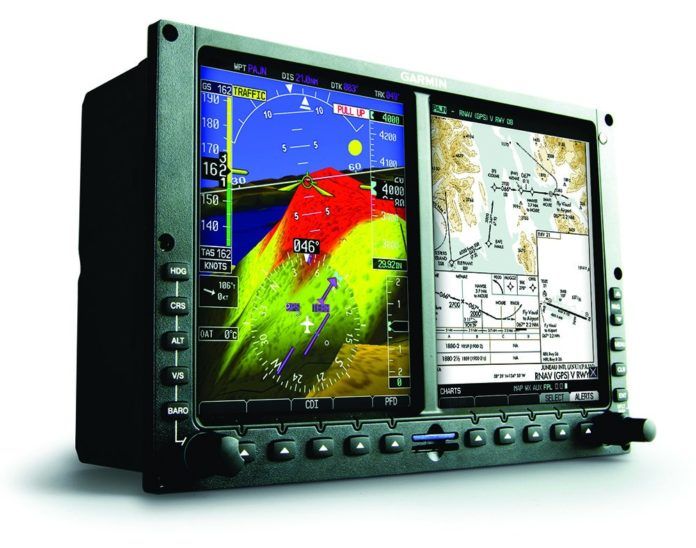

If you fly a glass cockpit, you have at least two or three screens—perhaps four with a tablet. Play a game with yourself to organize the information as efficiently as possible. Do you need multiple screens showing the same thing? Or is a screen better used for flight plan data? Which items in the data blocks aren’t duplicated on your PFD? What layers of data are best on or off?

For example, when flying with dual GNS 430s in VFR, it’s common to have the traffic page up on the number two screen. But in IMC, that’s a wasted screen. What else could you put there? The exercise not only improves your facility with your avionics, it keeps you engaged with useful data. Back to that traffic screen, the GTN 650 has the same screen, but you can use the more versatile map screen instead and configure it to show traffic. The benefit is that you can then also layer on other data, like terrain. Now the traffic screen doubles as a terrain warning screen.

Do you fly approaches with a terrain screen in view, or synthetic vision? How about a profile view? You probably have these options available, but they do nothing for you if you don’t make them an intentional, routine part of your cockpit organization.

This may get you digging deeper and uncovering useful features as well. The GTN 650s were driving me nuts for switching between screens. SOP is to push “Home” and drill down. (The thing needs a “recall” button to swap between favorite screens, like a TV remote.) But then I found out tapping the waypoint on the default nav page will call up the flight plan page. Now I can toggle from default nav to map or flight plan and back in one tap.

If Nothing Else, Nearest

I was recently flying VFR with a pilot who routinely verbalized his best nearest airport throughout the flight. That’s a good idea for both safety and engagement. When you feel your mind wandering, play The Nearest Game. Don’t just say, “My nearest airport is Cowtown, over there.” Go so far as to verbalize the bearing and then brief the airport.

Really. Punch up the runway information and frequencies. Check the weather and decide which approach or pattern entry you’d use. Scan the A/FD or other info as if you were actually diverting. Not only does it keep your head in the game, it standardizes your airport briefings. Then as you approach your destination, you do it one more time, but this one counts.

And come the day when you actually divert, for just an unplanned burger stop or because you actually went missed and need a real alternate, the effort is quick and effective. You do it all the time.

It’s Not a Crutch

Let’s stop saying, “Don’t use GPS as a crutch.” A crutch is something to temporarily empower you until you no longer need it. We don’t temporarily use GPS to power moving maps or fly approaches to 200 feet. GPS is a permanent tool you can wield like a master—or swing like a hack.

The core issue is engagement. If turning off your GPS gets you to check your engine gauges more often, fine, turn off your GPS. Practice with one of your many screens disabled, for sure. You should even practice a diversion and approach without GPS now and again. (There are such things as GPS outages.)

But don’t just randomly invoke oddball situations and delude yourself that leads to better SA on a flight next month. Instead, institute practices that leverage the technology to improve your SA and capabilities more than the 1975 pilot could dream. Rather than turn off your avionics, use them better, smarter.

Jeff Van West admits he’s the kind of gadget geek that, the first time he ever drove a Prius, he had to immediately pull out the manual to see what “B” meant.