Preflight briefings are a must. It’s not only common sense; obtaining basic information related to an IFR flight is required under 14 CFR 91.103, including “weather reports and forecasts, fuel requirements, (and) alternatives available if the planned flight cannot be completed.” This by no means covers everything, and thanks to popular demand (and recent adjustments in the rules), it’s largely up to us to get what we need.

Online self-briefings and in-flight weather have become the primary method for many pilots. With all the electronic resources available, we seldom have to deal with Flight Service directly. If you choose not to, however, you’ll need to keep track of what you’ve read, and what you take with you.

Here’s What You Get

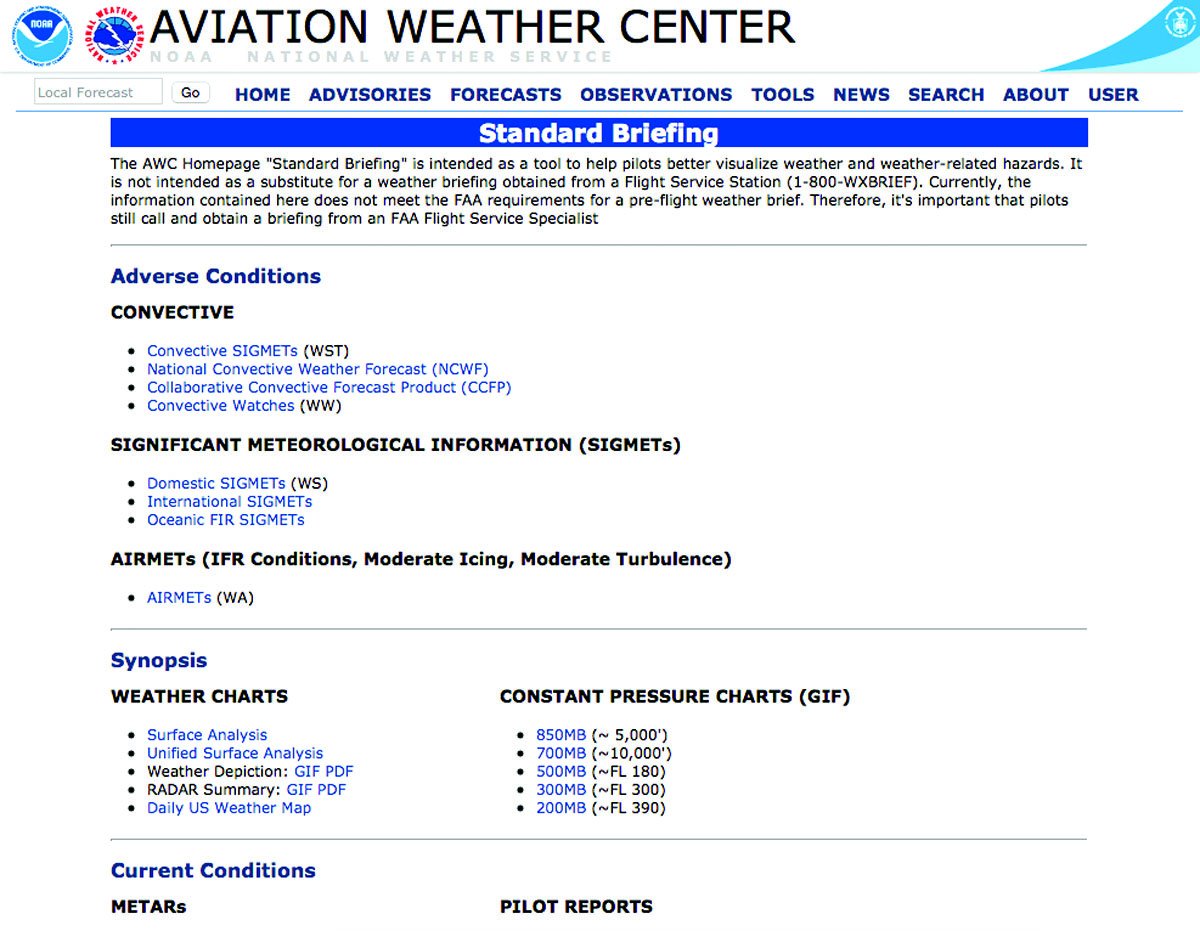

Whether you get a live briefing interactively with a human or an automated online briefing from Flight Service, you’re getting the same information: weather reports and advisories, pilot reports, forecasts, enroute advisories and NOTAMs. You’re even getting it in the same order every time. For purposes of our discussion, we’ll assume standard briefings.

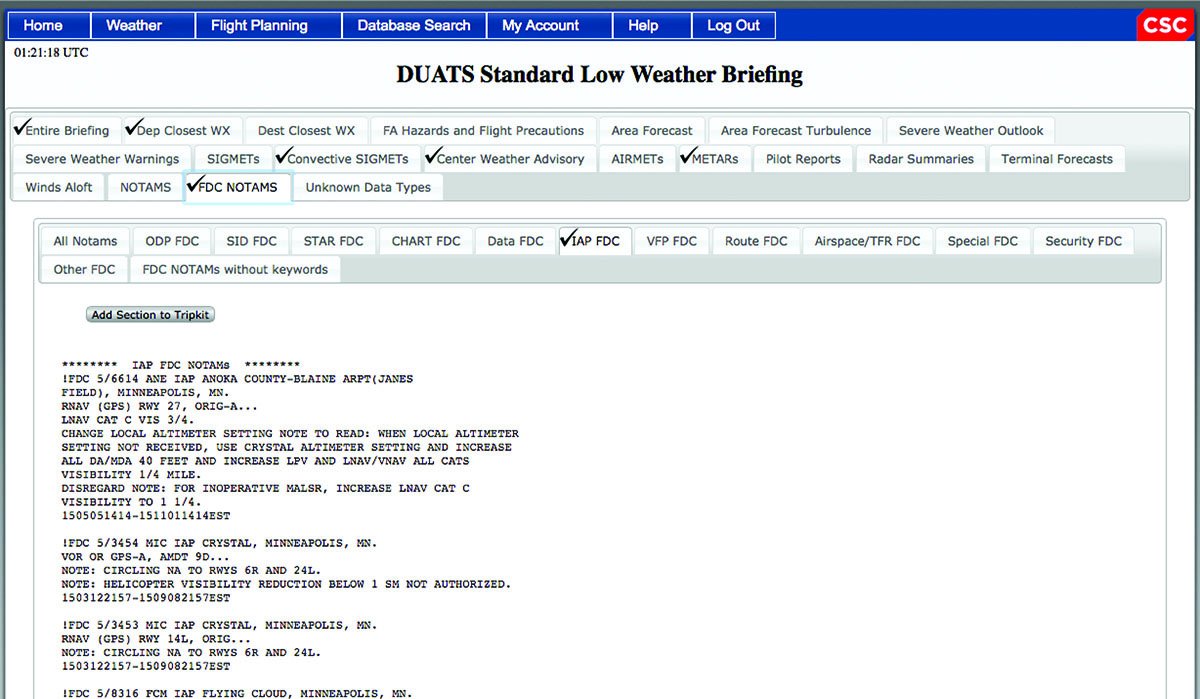

Whichever method you choose, this is consistent when you brief and file with the FAA’s Flight Service, now run under contract by Lockheed Martin. There’s a second FAA contractor, CSC DUATS, who provides online briefing and flight planning services only. You get the same briefing format from either company, and doing it self-serve online adds some neat features such as ready-made trip calculations, personalized navigation logs, and text alerts regarding your flight plan. (Earlier this year, a third FAA vendor, DTC DUAT, did not get renewed for the current contract cycle.)

What’s Official?

Before we go any further, we should delve into briefing legalities. The Web-based briefings from Flight Service and outside parties known until recently as “qualified” providers were designated by the FAA as meeting certain standards for reliability and the use of FAA data. Most operate with individual user accounts and logins and include all the standard items. Such resources include the National Weather Service, Fltplan.com and WSI, a briefing service used with individual accounts and available on computers found at many FBOs.

Briefings with such providers have long been synonymous with the more commonly used term “official briefing,” but there really isn’t such a thing as far as meeting 91.103 requirements for an IFR flight. Part 121 and 135 operations did require briefings from Flight Service or “qualified” sources, but in case you missed it, the FAA cancelled this designation about two years ago. This left the self-briefing process open as far as choosing the source.

It does help from another legal standpoint to have an online account for briefing and filing—proving you obtained one. Every once in a while, including after an accident, incident, or a regulatory violation, someone wants to verify that a flight briefing took place. That’s one advantage of calling Flight Service or using a provider that requires an online account and login for your briefing functions.

Phone calls to 1-800-WX-BRIEF are recorded (and briefers are friendly people who like to hear from you). Online FSS sources track your activity too, although one can’t tell specifically what you looked at or how closely you read those FDC NOTAMs. Being able to prove you got a briefing, and what you know from the briefing, is still relevant. This is one cautionary note if you’re “briefing” just by looking at some Web sites that don’t require logins.

Take Your Pick

Now, we get to the fun stuff—the apps. Applications like Garmin Pilot, ForeFlight and WingX Pro that connect to a Lockheed Martin or DUATS online account, all let you brief and file, but they include conveniences like weather and TFR overlays on the charts. By now, most pilots want an all-in-one app with briefing and filing, flight calculations, a moving map, etc.

What about all the other apps out there? For the most part, they connect to the same FAA data, as well as the National Weather Service for weather information. So if you don’t have a Flight Service online account or haven’t talked to a briefer for several years, you really don’t have to unless you’re in a pinch.

The only time a phone call to Flight Service comes into play with any regularity is when you’re on the ground wanting a clearance from a non-towered airport with no radio frequencies in range. (For those of you who forgot, that number is 888-766-8267.)

One caveat of using some third-party providers is that it isn’t always 100 percent seamless to file online and know that everyone down the line sees it. Unless it’s filed on an app that works via Lockheed Martin or DUATS, Flight Service briefers might not have seen your plan because it went directly to Center and did not go through Flight Service.

As you might have learned from experience, this would only be an issue if you called Flight Service to change or ask about something on that plan you filed and the specialist couldn’t find your flight plan. Not the end of the world, but naturally, that’s the time you really needed a person to get a hold of it.

In-Flight Self-Service

Just as live interaction with Flight Service briefers has dropped off in recent years, calling up a Flight Service specialist enroute is secondary to self-serve functions. (All Flight Service communications via radio are operated by Lockheed Martin.) Instead of telling Center you’re going off-frequency to call for a weather update or make an inquiry about your destination, you’re looking at your EFB for the radar overlay or checking an approach NOTAM loaded onto your chart. If so equipped, you can get MFD displays of updated radar and METAR/TAF data at airports.

The combination of self-briefings, EFBs and in-cockpit weather data have all but replaced the need for a mid-flight chat with FSS on the radio. The FAA is responding accordingly. For starters, Hazardous In-Flight Weather Advisory Service broadcasts via enroute VORs are getting decommissioned along with the VORs themselves. And this is why the FAA in October cut the dedicated Flight Watch frequencies (including the universal 122.0) and consolidated its in-flight weather services into the enroute Flight Service frequencies.

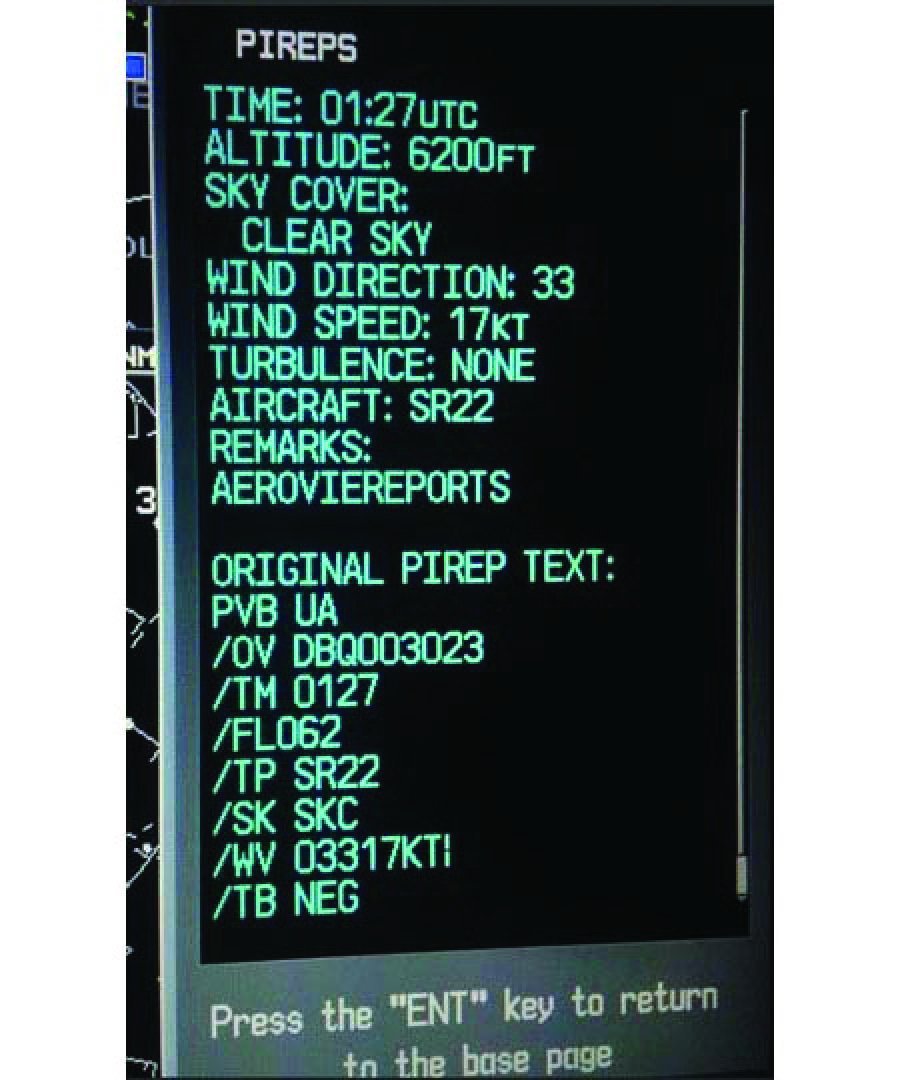

Recall that Flight Watch (formally called EFAS, Enroute Flight Advisory Service) was only for enroute weather updates and PIREPS. Not that the enroute resources via radio are going away, but the number of frequencies by which you can reach Flight Service for those resources is being reduced. Most of us won’t miss this at all. When was the last time you told ATC, “I’ll be back,” and went over to FSS to chat with them? When it comes to in-flight information, Flight Service now plays a supporting role, as does ATC for some inquiries.

The same goes for pilot reports. You can file them online, and even send them electronically in flight when so equipped—another feature advertised by Lockheed Martin. It’s still convenient and a good idea to tell ATC about brief or timely weather observations, such as turbulence or icing conditions, but the full PIREP has other means of delivery. The FAA also is encouraging pilots to submit them via the NWS Web site, although in-flight Internet access for the piston crowd is unlikely to become common anytime soon.

LIFR Briefing

Whichever app you pick, an important aspect of self-service is to make sure you’re consistent, starting with the standard briefing. Amid rumblings that Flight Service will further consolidate its operations, you’ll want to get used to this if you haven’t already. Take along that briefing information you looked up and have the tools you need in flight to check things as you go.

Departing on a 300-mile flight with 300-foot ceilings much of the way? Pull up a standard briefing based on the route you’re planning and make sure you cover each segment. The order can be your preference, as long as you don’t forget a section. Some providers, such as DUATS, have a checkoff feature where you can click each section to remind you what you’ve looked at in what’s usually a lengthy roll of text.

For instance, in a November briefing from St. Paul, Minnesota to St. Louis at 9000 feet, you’ll likely check freezing levels and icing before you see the surface conditions. NOTAMs for localizer outages or runway closures will be priorities over MEA changes enroute, although you will review these at some point. If it’s a clear day in June, ice and ILS approaches won’t be at the top of your list, so the sequence will shift.

In either case, start with the national weather maps so you know what general conditions you’re dealing with and what weather might be headed your way. Or, if you want a method that works year-round, begin every briefing with weather checks from point A to B, then move back to the departure airport to start checking non-FDC NOTAMs, then FDC NOTAMs. NOTAMS are now listed by category, such as SIDs, STARs, and Airspace/TFRs. Better yet, just download everything to your portable.

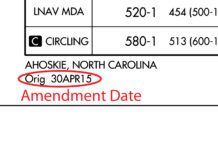

Notices are the most tedious part of any briefing, and it’s easy to miss things. While the FAA has improved the cumbersome NOTAM format, it’s still not easy to find information pertinent to the flight in question. At any rate, there will always be countless NOTAMs moving in and out of the system and it takes time to check out what you’ll want to know, like changes in obstacles or approach procedures. It pays to be thorough.

Next are RAIM and ADS-B checks. The normal briefings might not include a reminder to look at predicted outages around the country, so depending on the equipment you have on board, you’ll want to put this on your checklist. Checking RAIM for predicted outages before firing up your GPS isn’t a bad idea, as they can pop up with plenty of notice. The official Web site is http://sapt.faa.gov/default.php.

Whatever technique you use to brief, file and update, use your resources consistently on the ground and in the cockpit. Flight Service is still around with real people to assist, but such one-on-one help could become increasingly scarce in the future.