ATC has myriad restrictions and rules, all of which are designed to maximize safety and, believe it or not, also maximize overall efficiency. But, sometimes that overall view of things just doesn’t work out for you. You’ve got three choices: 1) Comply with the instruction, 2) Tell ‘em you’re unable, and 3) Work out an alternative to meet your needs and the controller’s.

Each option has its time and place, and in any given flight you might use each of the three at different times. The trick is knowing what you can do, what you can’t, and how to tell the difference (to paraphrase a well-known saying).

First, define what you are looking for and why. Typically it is a change in the route or a change in altitude. The reasons may be economy (shorter or more efficient routing), weather, terrain or even just personal preference because you like the view over there a bit better.

Just Go VFR

The first and perhaps most obvious but limiting trick in your arsenal is to convert from IFR to VFR. It’s limiting because you need VMC, you lose the airspace protection offered by IFR and you’re limited to 17,500 MSL. If it works for your situation, though, it can be as simple as cancelling your IFR clearance. You might consider this when an IFR clearance is required to reach an altitude where there is VMC, and the flight can be safely continued in VMC.

There are two ways to do this. One is to request a specific clearance— IFR to VFR-on-top, for instance—before takeoff. You then inform ATC when you are more than 1000 feet above the cloud deck. You cancel, and proceed normally under VFR. If you do not reach VMC, the flight plan continues with an IFR clearance. (See “On Top of the World” in August 2013, for a full discussion of VFR-on-top.)

If your departure can be conducted in VMC and you want to avoid a complex departure procedure or bypass some traffic, you can request a VFR climb as part of your IFR clearance. If granted, you will be given a VFR limit of an altitude or a fix. You’ll be responsible for your own traffic and terrain separation until reaching that limit.

Another option is to simply depart VFR and pick up a clearance while still in VMC. As was discussed in December’s “Pop-Up Clearances,” this can be done as a pop-up where the first time ATC knows about you is when you make radio contact. This has risks. ATC may be too busy to comply with your request. So you must have a Plan B—such as filing through Flight Service—if a clearance isn’t available.

If ATC can’t accommodate your request for an IFR clearance, a fallback position is to tell ATC you will continue to monitor the frequency. This often results in de facto VFR flight following, and in some cases ATC will ultimately issue the requested instrument clearance. “Aircraft that was calling several minutes ago for an IFR clearance, say position and request.” This works best if you were given a transponder code, because once you’re in the system, a request to convert to an IFR clearance is a lot quicker and easier for the controller than if he has to start from scratch.

A safer option than the pop-up clearance is to file and pick up your clearance in the air, after you launch. You might start your clearance over a nearby VOR. Depart and climb in VMC, pick up the clearance, and continue your flight, presumably into IMC. This option is not foolproof, though, as it still requires a controller with enough time to work you into the system.

There is also the reverse option, converting from an IFR clearance to VFR. A typical scenario is where ATC clears you to a lower altitude than you would prefer, or conversely, keeps you higher than you need for a comfortable descent. Once you’re in VMC with required cloud clearance, you can cancel IFR. If you do, request flight following. This most likely will be granted, as you are already established in the system.

Perhaps the altitude ATC needs from you is simply for conflicting traffic. If so and if you can spot the traffic, consider requesting visual separation. This might work with TRACON, seldom with Center, and never in Class A airspace.

Telling ATC you are proceeding direct can straighten some arrival procedures, but be careful not to violate any airspace. Remember, while VFR you’re ultimately responsible for airspace, traffic and terrain, even if you’re on flight following.

On descent, VFR-on-top might again be an option. This has worked for me when descending out of cruise and ATC clears me lower than I want at that point. When granted, VFR-on-top allows flight as high as 17,500 along the previously cleared route at VFR hemispheric altitudes.

ATC might place a restriction on your altitudes, such as, “Cleared VFR-on-top at or above 7500.” Or, they might remind you to “Advise of any change in altitude,” which is a requirement anyway. As this is still an IFR clearance, if you again encounter IMC, you can just request an IFR altitude, which ATC is required to accommodate. VFR-on-top clearances are most often declined near major airline hubs where ATC tightly controls aircraft altitudes.

VFR-on-top isn’t all that common. I once had a controller mistakenly think I was cancelling IFR when I requested VFR-on-top, so a little careful communication might be in order.

With Discretion

There are times on arrival when ATC assigns you lower but you prefer to remain at altitude longer—maximizing economy, taking advantage of a strong tailwind or minimizing exposure to turbulence or icing—and you need to remain IFR. I’ll acknowledge the assignment then ask, “Any chance that descent can be at pilot’s discretion?”

Pilot’s discretion is a wonderful tool for altitude optimization. It allows you to fly the descent profile you want. If it’s declined and I consider the descent to be a problem, I’ll start down—I don’t want to argue—but I might explain why I don’t want to descend that early or to that particular altitude. “Roger, descending 8000. I’d like to avoid possible icing between 9000 and 7000.” When I do that, it’s more likely I’ll get something better.

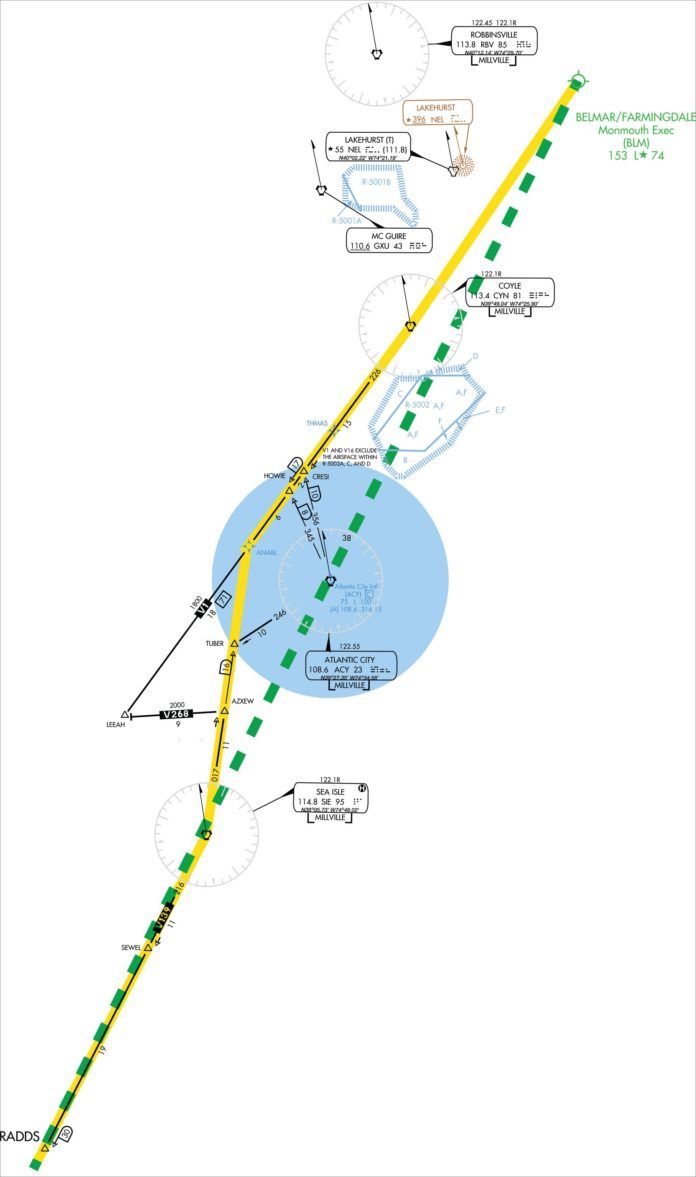

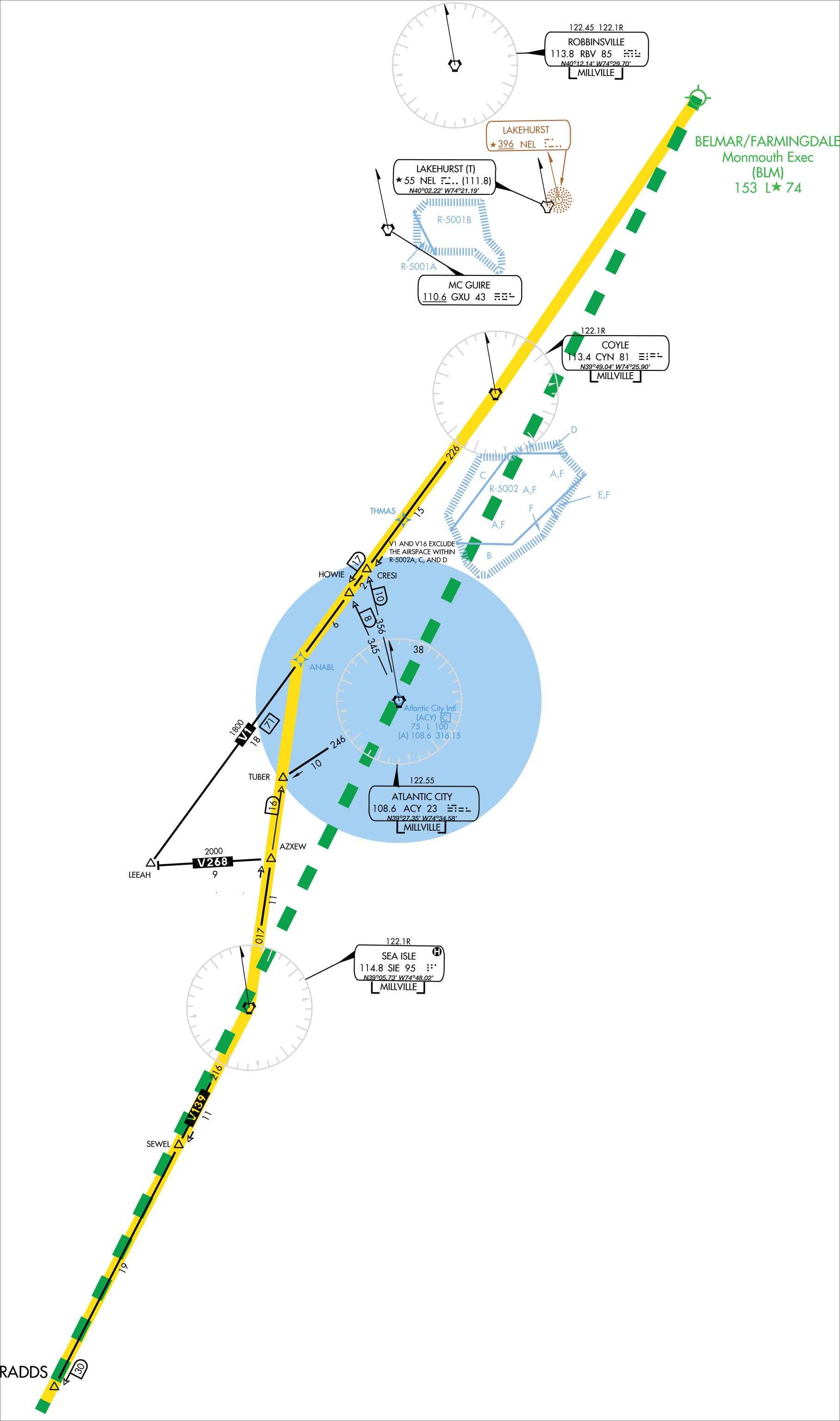

A crossing restriction is another form of a pilot discretion altitude change. Asking for a crossing restriction rather than just a lower assignment can work well if the controller just needs you at an altitude by a fix due to an agreement with another ATC facility. If you can get, “Cross RADDS at 11,000,” you can start your descent any time you wish as long as you meet the restriction. Vertical GPS profiles greatly simplify making the restriction. A word of caution is in order, here. NASA ASRS and similar reports show that missing altitude crossing restrictions is one of the most common errors. If you get a restriction, make sure you don’t forget it and find you need to lose 5000 feet in the next two miles.

If you fly a turbine or turbocharged recip in the flight levels, it can be economical to delay a descent for as long as practical. I often fly my turboprop TBM 850 into Monmouth Executive (BLM) in New Jersey. See the chart for my typical clearance. Occasionally, they’ll give me a 7000 crossing restriction at RADDS—over 100 miles from the airport. There’s no way I want to burn all that fuel down that low for that long, so if it’s VMC, I’ll just start a slow descent. Once I am through FL180, I cancel IFR, and level at 17,500 VFR.

Maybe Later?

“On request” is a very powerful phrase. As operationally appropriate I request an altitude, route, approach, runway, etc. ATC may respond in several ways, and all but one are advantageous. I seldom receive “unable,” unless the frequency is jammed, in which case I avoid requests unless there’s an operational imperative.

Consider the last possibility of “unable” in more detail. Flying south along the U.S. east coast, I was cleared direct to the Charleston, South Carolina VOR (CHS). The NEXRAD images were ugly, showing a level 4 to 5 thunderstorm directly over the VOR, and bad weather extended from there far to the west. The only clear area was over the ocean east of CHS. I requested a deviation to the east, which ATC declined, citing military operations in the warning area over the water. I replied I really needed a deviation to the left due to weather over Charleston. ATC asked, “Are you declaring an emergency?” I politely replied, “No, but if the clearance requires direct CHS, I may have to declare an emergency and make a 180.” (Note, I did not declare an emergency). This was shortly followed by a clearance through the warning area to the east of the weather.

There are times like this where there is not yet an emergency, but ATC needs to know the possible seriousness of the situation.

When the controller can’t grant your request then, but might be able to later, he’ll often reply, “On request.” I do not pester the controller further, and often the request is granted in due time. If not, upon hand off to the next controller my first communication is “N4MD Flight Level 300, direct destination on request.” The “on request” gently reminds the controller of the outstanding request, whether it was passed on to him or not.

The “request” option is helpful in other situations. It allows a controller to grant a request at any future time when reasonable, and might set up a relay of the request to the next controller. I may request a specific instrument approach procedure, visual approach, or a specific runway if these are options that would not normally be expected. ATC does not know where I park on the airport, perhaps I want to fly an approach I have not flown before or perhaps unexpectedly the airport becomes visible. The request is worth making early, though it may not be with the controller who can grant the request. The request allows the controller to set up a more efficient handoff, and often I do not have to repeat the request to an approach or tower controller.

The most powerful tool enroute is the request for direct. The ability of a controller to grant direct depends upon many factors: altitude, airspace, traffic flow to major hubs, Letters of Agreement with other facilities, etc. However, a “Request direct SNABS” or “Request direct destination” indicates you can navigate direct to a point. These will often be granted. The latter request often provokes the response, “say proposed heading (to destination).” So be prepared to answer. In my aircraft, I center the heading bug if necessary and briefly place the autopilot in heading mode. I then enter direct to the requested point to obtain the required course.

A seeming detour in a route clearance may be to keep you clear of special use airspace. While GPS can guide a plane to avoid airspace within feet, ATC radar needs to place you 3 to 5 miles outside airspace borders to insure you are safe. Nevertheless, when you see you are clear, a request for direct will often be granted.

You often hear the pros asking, “Any chance for a short cut?” This is a simple, polite way to ask to cut a few corners and is almost always accommodated.

You often can get a direct routing off shore, but you may have to ask for it as few GA aircraft are suitably equipped for over-water flight. If you’re comfortable with that routing, just ask for it.

Of course, not all unfavorable clearances can be rectified. I have not been able to escape commanded IFR descents to very low altitudes beneath Class B airspace and have navigated St. Louis, and Chicago at 2000 feet AGL IFR when landing at satellite airports. I am still dragged across Philadelphia at 6,000 until well west, though requesting FL 300.

The exercise is to think through what your operation requires or would benefit from, and then provide ATC with an alternative. ATC typically will not offer such options, but in most cases grants reasonable requests.

Ian Blair Fries, M.D. is a Senior HIMS AME, ATP, CFII. He flies a TBM850 for business, and has more than 5000 hours in the air. A frequent aviation speaker and freelance writer, he collaborates with the AOPA on medical and regulatory issues.