There are three ways to arrive at an airport when operating under IFR: a standard instrument approach procedure (IAP), a visual approach and a contact approach. A great way to bring hangar flying to a screeching halt is to ask about a contact approach. A lot of IFR pilots know that it is some sort of visually-flown maneuver, but when asked how it differs from a visual approach, blank stares often ensue. Let’s fix that.

Contact vs. Visual

A visual approach is conducted to an airport that is legally in VMC. “Reported weather at the airport must have a ceiling at or above 1000 feet and visibility 3 miles or greater,” says AIM 5-4-23. When the visual approach is to an airport without an operating control tower and has no weather reporting service, ATC can initiate a visual approach provided there is “reasonable assurance” that the weather at the airport meets the 1000 and 3 VMC minimums. This is where a PIREP can help grease the wheels for those behind you.

If the field is VFR, your other option is to cancel the IFR flight plan with ATC and land under VFR. This has both pros and cons. The first advantage is that you won’t be the one who forgets to tell ATC that you landed safely and that your IFR flight plan can be closed if there’s no tower to do it for you. Another advantage is that ATC separation standards are reduced for VFR aircraft, and if you’re operating in some busier airspace, it may provide ATC with a little more flexibility and utility to help the system run more smoothly.

The biggest disadvantage is that as soon as you cancel, you’re bound by the VFR cloud clearance and visibility requirements of 14 CFR 91.155. On a visual approach, your only restriction is that you remain clear of clouds. (Some certificated operators have more stringent requirements.) If canceling IFR and still in Class E airspace, you need to remain 500 feet below the clouds with 3 miles of visibility until reaching Class G airspace, if any. With Class E surface or extension areas, you may have to wait until you are below 700 feet AGL or even landing before you’re in VMC.

Of course, you’re also no longer IFR. If the weather changes, or things aren’t quite as visual as you expected, you are no longer ATC’s IFR priority and you’re hoping for a “pop-up” IFR clearance—all while trying to stay in VMC. All of this, of course, is dependent on the destination airport being VMC.

Contact Approach Defined

The best way to think of a contact approach is as a visual maneuver to an airport reporting IMC. Since the airport is in IMC your only other choice is an actual instrument approach. This means you should prepare for that approach while hoping it’s good enough for a contact approach. So, a contact approach is a way of arriving visually at an airport that is reporting less than 1000-3, provided certain criteria are met.

AIM 5-4-25 tells us what we’ll need to pull this off. First, we’ll need to be operating clear of clouds with one-mile flight visibility—you forfeit your authorization to punch through clouds and you must have and maintain one mile of flight visibility all the way to landing. If you meet that requirement, you are free to request the contact approach. You have an out, though, if you find that the conditions aren’t cooperating. You’re still on an IFR flight plan and you can cancel the contact approach and request vectors for an instrument approach.

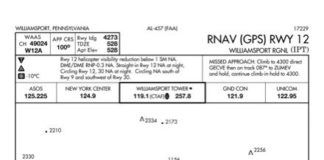

ATC has its own requirements to issue a contact approach clearance. First of all, the airport (not necessarily the runway) must have an IAP. Therefore, the contact approach won’t be a cheesy way to sneak IFR into an airport that doesn’t have an approach. The FAA specifically thought of that. AIM 5-4-25 says that the contact approach isn’t to be tacked on to a standard IAP for the purposes of getting below the clouds at one airport, only to sneak over to a nearby airport that lacks an IAP.

Another requirement is that the reported ground visibility at the destination airport must be at least one statute mile. This is in addition to the one mile flight visibility that you need throughout the contact approach. If your airport is only reporting RVR for the active runway, then it pays to know your RVR/SM equivalencies. (Hint: 5000 RVR = 1 SM.) The AIM and the Air Traffic Control Handbook (FAA Order 7110.65) both say that approved separation is applied between the contact approach aircraft and any other IFR or Special VFR aircraft. In practice, this means that it’s extremely unlikely that you will be cleared for a contact approach if there’s another aircraft preparing for the IAP.

The controller handbook even says “Unless otherwise restricted, the pilot may find it necessary to descend, climb, and/or fly a circuitous route to the airport to maintain cloud clearance and/or terrain/obstruction clearance.” This is fair warning to the controller that standard separation may be difficult to predictably maintain.

How the Pros Do It

Many commercial operators put additional restrictions on the contact approaches—if permitted at all—through their operations specifications. In doing so, they generally divide contact approaches into two categories: Runway in Sight and Airport Not in Sight. The Runway-in-Sight category would be for those instances where perhaps the airport is reporting, say, 400 overcast and 10 miles visibility, and the overcast which is making the field IFR is located at the far side of the airport where the ASOS is located—leaving the first half of the runway in the clear and the second half covered. This is common at coastal airports, or other locales where fog or similar low cloud layer may advance and retreat based on wind and/or solar energy.

The Airport-Not-in-Sight category is a little fishier. It’s reserved for circumstances where the ceiling is not so much a factor but the visibility is down to not less than one mile, typically in haze or mist, or sometimes smoke from nearby fires.

With decent familiarity, some might fly the contact approach by following the interstate to the big box store to the hamburger joint and turning north to find the threshold. Since the pilot is responsible for his or her own terrain and obstruction clearance during a contact approach, familiarity with the area and particularly the obstacles is crucial. Even knowing the area, there is still a large element of risk.

Common ops specs restrictions reflect the hazards of these two scenarios. With the runway in sight, the primary restriction is usually the admonition not to descend when above a broken or overcast cloud layer—the “Sucker Hole Prevention Clause.”

The Airport-Not-in-Sight scenario naturally comes with additional restrictions. It’s not uncommon for commercial operators to require positive course guidance to the intended landing runway in order to descend, usually from the FAF altitude or perhaps MVA, when the runway is not in sight. This gets us into the realm of “why bother doing this?” That does give some insight into what the FAA truly thinks of the “feeling your way” contact approach. Bear that in mind next time you’re tempted to forgo the IAP for the local landmark-based, I-think-it-should-be-safe-to-descend-here contact approach.

Contact approaches cannot be suggested or offered by ATC; the pilot must request them. Think about that. The FAA lawyers did, and created a way to disavow any responsibility. You should make sure you can conduct the contact approach safely and that it’s really a better solution than a normal IAP.

Like pilots, not all controllers are familiar with the requirements of a contact approach. I once was denied a contact approach because there was no tower at the airport, which isn’t a requirement. I later delivered an appropriately highlighted section of the 7110.65 to the controller and subsequently got a contact approach to the same airport from the same controller.

Responsibilities

AIM 5-5-3 contains the pilot and controller responsibilities for the contact approach. Much of it is restatement of 5-4-25, with a couple of additions. First, it’s the pilot’s responsibility to inform ATC immediately if it’s not possible to continue the contact approach, presumably due to clouds or visibility. The controller’s responsibility is to ascertain that the destination airport has the required one mile of ground visibility, as should the pilot.

Additionally, the controller shouldn’t assign a fixed altitude for vertical separation; however, they should ensure that there is at least 1000 feet of separation below any other IFR traffic, consistent with the minimum safe altitudes outlined in 14 CFR 91.119. Lastly, it is the controller’s prerogative to issue alternative instructions if they judge that the weather conditions make completion of the contact approach impracticable. But then, you shouldn’t have requested it in the first place.

Evan Cushing is a former regional airline training captain who now works in a collegiate flight program, where his contact approaches usually amount to finding his way to the door at quitting time.