Flight is a study in contrasts, well beyond the obvious “thrust versus drag” equation. A brilliant blue sky rife with possibilities and adventure can quickly turn woefully lonely when your aircraft or the people in it are in distress.

No good pilot intends for an emergency to happen. Each item on an aircraft checklist, every scan of an instrument and every word of a briefing is one more brick in the wall fending off a potential crisis. Still, even if you followed every procedure perfectly, basic human error, mechanical failure or plain bad luck can plunk you in the deep end of the pool.

When you’re in the midst of a devolving situation, perhaps you’ll hear mental echoes of your flight instructor’s voice. Rely on your training. Go through your checklists. Keep a cool head and resolve the problem to the best of your ability.

What’s the most important thing after flying the airplane? Remembering you’re not alone up there. Air traffic control has resources at its disposal that can help you put it down safely, and they’re just a radio call away.

Reaching Out

Perhaps you recall 90’s sitcom character Dr. Frasier Crane, the psychologist who answered every caller on his radio show with his catchphrase: “I’m listening.” While air traffic controllers might not be neurotic psychologists, we are indeed on frequency and listening. ATC facilities are supposed to monitor both 121.5 VHF and 243.0 UHF “Guard” frequencies during operating hours. With a push of a button, we can also transmit on them.

Many aircraft, such as airliners and military flights, also regularly monitor Guard to meet either regulatory or company requirements. It’s actually encouraged for every pilot to do so, per AIM 6-2-4 (d). This dramatically expands the network of those who are listening to the emergency frequency. Chances are, if you call out on a Guard frequency, someone’s going to hear you. Even if you’re outside ATC’s radio coverage, helpful pilots already in contact with ATC can inform controllers of your situation.

Here’s a perfect illustration of this kind of ATC-pilot teamwork. Years ago, there was a Cirrus crossing the expanse of the Gulf of Mexico, from Florida to Texas. Flying far over water, outside of radar and radio coverage, he was supposed to reestablish contact with Center at a certain fix, but couldn’t reach them.

I heard him calling out for help on Guard, but when I replied, he couldn’t hear my transmissions. He was probably below my transmitter’s horizon. Fortunately, a United Airlines aircraft cruising in the flight levels overheard the exchange on Guard and established two-way communications with him.

Using the United crew to relay a few questions, I figured out the Cirrus’ position. I informed my supervisor. A few phone calls later, we had a good Center frequency for the frightened Cirrus driver. As I switched him to the new frequency, I told him to re-contact us on Guard if he got no joy on it. He never came back to me. A while later, I checked the FlightAware plot for the call sign, and was relieved to find he’d arrived safely at his destination.

Of course, if you’re already in contact with ATC on a standard frequency, there’s no need to change to Guard. Just advise your controller what’s going on. He’ll likely keep you on that same frequency unless absolutely necessary. When handling aircraft in distress, controllers are urged to minimize frequency changes. The last thing anyone needs is for a pilot in a critical situation to get lost in the wild forests of Frequencyland.

Start Talking

How do you get ATC’s attention on a busy frequency? The highly effective, shut-everyone-else-up method is beginning your transmission with “Mayday.” The phrase “Pan-Pan-Pan” can also be used for not-quite emergency situations, but ATC rules don’t make a distinction between the two. A controller hearing either of those terms understands one thing: A pilot needs help.

To provide that assistance, a controller requires the aircraft’s call sign, the nature of the emergency and the pilot’s desires. Put bluntly, answer these three questions: “Who are you? What’s wrong? What do you need?”

There’s no such thing as a “standard” emergency, and therefore no standard phraseology for getting across this information. Just speak plain English. “Mayday! Mayday! Mayday! Cherokee Six Three Bravo has smoke in the cockpit. What’s the nearest airport?” One single transmission like that can convey all the important data.

In my somewhat limited experience, pilots in distress often forget to use “Mayday” or “Pan” or even “emergency.” Don’t worry. By their very nature, emergencies have no standard format. Those words aren’t required for priority handling.

Section 10-1-1 (c) of FAA Order 7110.65—the ATC handbook—tells controllers: “If the words ‘Mayday’ or ‘Pan-Pan’ are not used and you are in doubt that a situation constitutes an emergency or potential emergency, handle it as though it were an emergency.” If it looks, sounds or feels like an emergency, we treat it like one.

Usually, we can fill in the blanks pretty well, especially when we hear certain terms. Any variation of “smoke” or “fire,” hydraulic, vacuum or electrical failure, uncertain landing gear status or loss of an engine will get a controller’s attention. If it’s not clear, ATC may straight-up ask, “Are you declaring an emergency?”

There’s also a fourth, very important question: “What’s your position?” If you were already in contact with, and identified by, ATC prior to the emergency, your location should be known. If not, squawk 7700, which will make your target light up on ATC radar scopes, triggering aural alarms and draw each controller’s attention. Once you’ve established radio contact, tell ATC your last known distance and bearing from a major fix, like an airport or navaid. This confirms the radar identification so we know for certain which one is you.

Your Move

Once ATC gets your identity, predicament and current position, you still need to answer the most critical question: What do you need? This is not something ATC can answer for you. Our lives aren’t on the line. We are here to provide information, support and coordination, but it’s all based on your request.

Even the relatively few pilot-trained controllers are strongly encouraged to “stay out of the cockpit” for liability reasons. I may have 10,000 flight hours in the exact same type of aircraft that’s in distress, but I’m not in the front seat, experiencing the same conditions as the pilot. It’d be like me trying to cure a perfect stranger’s undiagnosed, serious illness over the phone using WebMD.com and a gut feeling. I could inadvertently make things worse. If things ended badly, the victim’s attorneys would pave the road to hell with my good intentions.

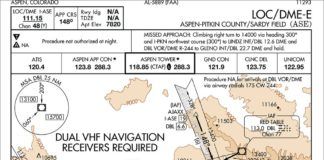

Use good judgment and make a decision. The sooner you tell us what you want, the sooner we can help. Did a vulture attack your windshield? We’ll vector you to the nearest suitable airport and provide you with its distance, runway dimensions, and local weather if available. Is your landing gear not showing down and locked? We’ll check it visually and have the rescue trucks standing by. Running dangerously low on fuel in IMC and don’t have local approach charts? We can read the fixes, headings and frequency to you, and call out the IAF and FAF as you cross them.

There are certainly times when a pilot’s needs are obvious. I once had a Cessna Skyhawk on downwind in my touch-and-go pattern, sequenced to follow a regional jet. The Skyhawk pilot reported a sudden, severe drop in engine power. The situation had only one reasonable outcome—get the Skyhawk on the ground, fast. Without hesitation, I sent the regional jet around and cleared the Skyhawk to land on any runway he wanted. He set it down without incident.

Emergencies can happen so fast that you don’t even get a chance to call ATC. AIM 6-1-1 and 14 CFR 91.3 make it clear that a pilot can—rightfully so—deviate from ATC instructions to save his own skin. We don’t know what you’re experiencing and you may not have time to tell us, so act first and talk later. Rule number one is always “fly the airplane.”

Here’s one wild example. One of my buddies at another facility cleared a single-engine turboprop for takeoff, followed by a business jet. As the prop began his climb, the engine popped an oil line and peed most of its lubricant all over the field the below. The pilot hooked it back around towards the same runway he’d just departed, opposite direction, just as the jet was rotating. The turboprop jinked right, missed the jet, and landed safely on the remaining runway. The tower crew was still in disbelief as they called the rescue vehicles. That’s AIM 6-1-1 at work, right there.

Someone Ate the Fish

We’ve discussed mechanical issues that befall aircraft themselves, but let’s not forget human factors. With so many people zipping across the nation’s skies daily, it’s inevitable that illness will befall a certain percentage of them. There’s a possibility the next medical emergency could happen in your aircraft.

Airliners naturally get the lion’s share of medical emergencies since they carry the highest volume of people. I’ve personally encountered more than a few of them. Some were unplanned diversions to our main airport, like a 737 with a cardiac arrest situation, or an MD-83 with an unconscious passenger. General aviation and the military get their licks in too. Students pass out during flight maneuvers and stay unconscious. Turbulence bangs up light twins.

What most of these instances share is that the pilots advised ATC of the situation with plenty of time for us to act accordingly. It can take a few minutes for paramedics to arrive at the airport and get escorted inside the security fence. Waiting until you land to speak up is not in your best interest. Case in point? The center had informed us about the 737 cardiac situation when it was still fifty miles away. A ambulance was already waiting at the gate when the airliner landed.

Each of the hundreds of ATC tower and radar facilities nationwide has different procedures for coordinating emergency medical services. They vary because, well, every facility, airport, city, and hospital infrastructure is different.

Tower controllers at larger airports will notify their airport operations staff of the aircraft’s estimated arrival time and the sick person’s condition. Operations then summons the paramedics and, if there isn’t an on-site team already, escorts them onto the airport property. Other towers may coordinate with local FBOs or dial 911 directly. At non-towered airports, the overlying radar facilities have contact numbers for the airports underneath their purview.

Emergencies of all types happen every single day, and most of them have happy endings. While ATC can certainly have a role in those outcomes by providing a helping hand and a calm voice, it’s your decision-making and timely actions that ultimately save the day.

Tarrance Kramer’s experienced no shortage of weird situations while working traffic in the Midwest. His favorite words when filling out paperwork on emergencies? “Landed Without Incident.”