NextGen is such a simple word, yet it implies so much. This FAA effort to redesign the entire National Airspace System’s underlying technology and procedures has been underway for years and will continue for many more. Billions of dollars and millions of hours have been dedicated to new systems, new airspace design and new user training.

The FAA has promised the sky—or at least a change to how we fly through it—through neatly packaged talking points: Increased safety, decreased costs, better communications, reduced delays.

With bureaucracy as its father and the FAA as its mother, you may be surprised to know that the NextGen baby is developing nicely.

ADS-B

If you haven’t heard of the FAA’s 2020 ADS-B mandate, it might be time to leave your cave. Do you fly in Class A, B, or C airspace? Operate within the Mode C veil of a Class B airport? Fly above 10,000 feet MSL over the 48 contiguous United States? Well, your airplane’s going to need ADS-B Out by January 1st, 2020.

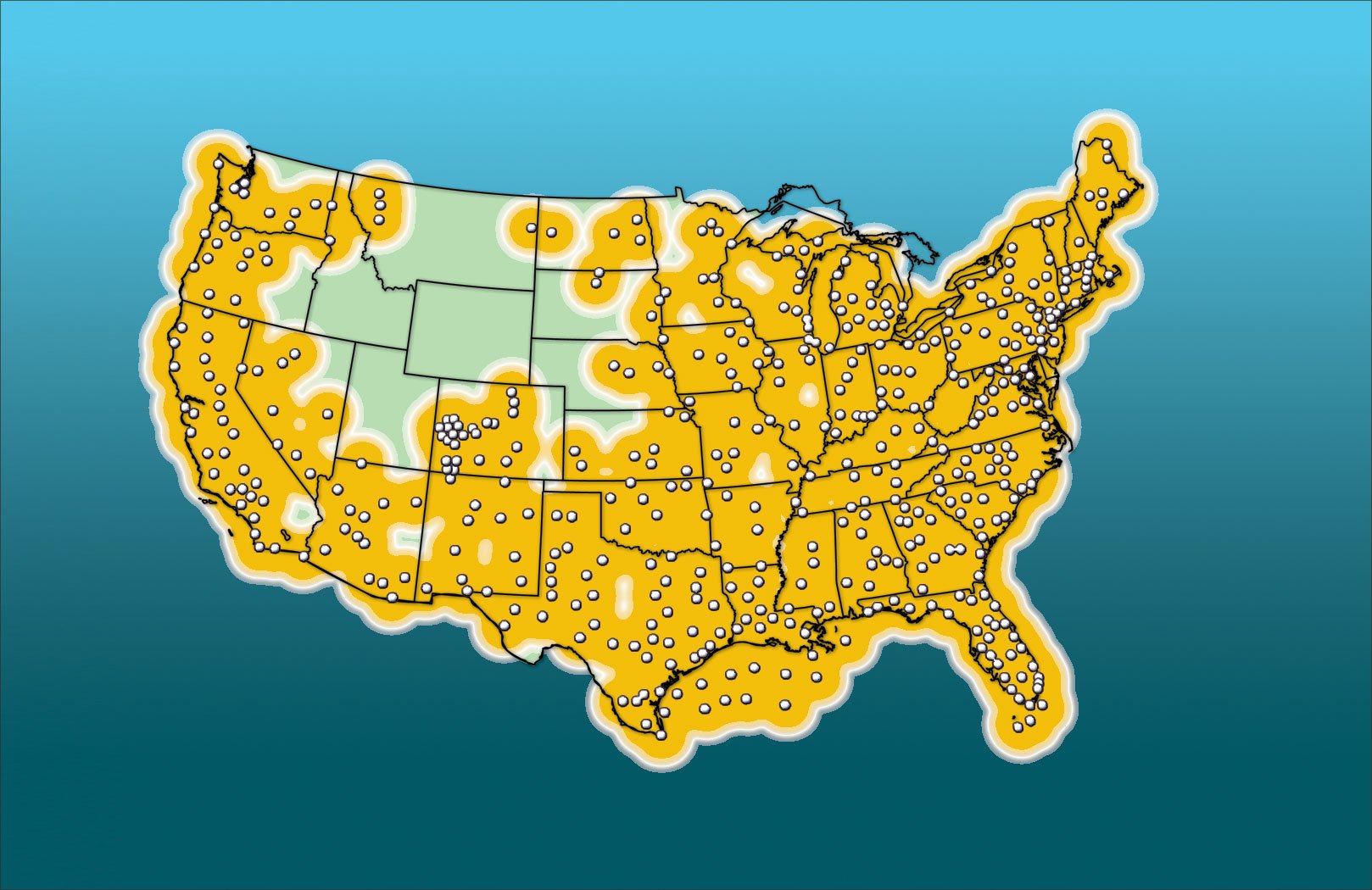

The FAA is doing its part to get the ADS-B sensor network fully operational by that day. Six years out, nearly three quarters of the U.S. already has ADS-B coverage. As of May 2013, the largest area without coverage is the Rocky Mountains, between Nevada and Kansas, stretching north to Montana.

Early adopters are already taking advantage of the existing system. Weather and traffic services like FIS-B and TIS-B (Flight Information Service-Broadcast and Traffic Information Service-Broadcast) are becoming available in new areas every month, offering more pilots live traffic data, NEXRAD radar imagery, weather reports and other data transmitted via ADS-B to cockpit displays.

The FAA is making the transition pretty seamless for ATC. Before ADS-B, all of the scopes at our approach control relied on a single radar antenna. It spun every six seconds, meaning our traffic would update only ten times a minute. We played catch-up with fast movers.

We recently had six ADS-B sensors installed nearby. They continuously search for transponders in all directions. The signal from those sensors is paired with radar data in what’s called Fusion mode. Traffic movement on our scopes now updates every second, creating a real time traffic picture. Targets also now indicate if the aircraft is ADS-B equipped or still using legacy transponders.

Down to Minimums

As a byproduct of ADS-B and the aviation community’s increasing reliance on GPS, the FAA is reducing the number of ground-based NAVAIDs. Over 80 percent of VORs are approaching an expensive age of 30 years. In 2012, the FAA announced its plan to eliminate half of all VORs to reach what it calls the Minimum Operating Network (MON).

The MON isn’t as skeletal as it sounds. The FAA plans to keep VORs in service at 30 large airports and in mountainous areas like the Rockies and Appalachians. Even beyond those key areas, no aircraft above 5000 feet will be more than 100 miles from VOR signal coverage within the contiguous 48 states.

When a VOR goes, so do the elements built on it—instrument approaches, Victor routes, and Jet routes. Therefore, if a VOR is targeted for shut down, the FAA ensures each decommissioning proposal includes a call for public input.

The FAA does seem to be listening. The Bridgeport, Connecticut VOR (BDR) needed over $8 million in repairs for water damage and structural cracks. In December 2012, the FAA proposed decommissioning. This one NAVAID served approaches at 14 airports, so affected pilots and the AOPA took up the fight. In May 2013, the FAA cancelled the decommissioning. Too many users would have been affected and there were no other local NAVAIDs to take up the slack.

Nonetheless, expect VORs to drop like flies through 2020. When a VOR gets marked for decommissioning—such as Portland’s PDX NAVAID—its airspace elements are restructured. New GPS fixes may be created, forming the foundation for possible GPS-based T-Routes and Q-Routes that are supplanting and replacing NAVAID-based Victor and Jet routes.

Taking a SWIM

NextGen isn’t just about rerouting airplanes. It’s about simplifying the way FAA processes and stores information relevant to those airplanes. Let’s face it, the older architecture is a mess.

When you get a preflight briefing, Flight Service or your favorite app presents all of the relevant weather, NOTAM, TFR, and other info in a tidy, easy-to-digest format. What’s not apparent is that the raw source data for all of that is scattered throughout multiple, independent computer systems that have no common language. Programmers worked hard to make it accessible for you.

Enter the FAA’s System-Wide Information Management (SWIM) effort. Flight-related data pulled from multiple sources will be fed into SWIM’s unified “cloud” computing system. Developers who want to distribute that data to pilots, airline operations departments, and other end-users now just need to pull from that one SWIM source, instead of interfacing with multiple disparate systems.

In time, most aviation data will be processed via SWIM. Whether you’re getting a briefing, filing a flight plan, submitting a PIREP, getting live traffic updates, checking a NEXRAD feed via ADS-B—all of it, everywhere, will likely go through SWIM. The goal is a consistent system that provides the same standardized services to all users instantly and automatically.

This will improve ATC connectivity. For example, our TRACON and tower both have Information Status Displays showing local METARs, SPECIs, and NOTAMs from relevant airports. We manually type that data into the system every time a report comes out. At the end of 2013, the FAA began rolling out a new system that features SWIM connectivity. By 2016, the system will be automatically populating weather and other relevant data from the SWIM connection.

Operational Advantage

Processing basic flight and briefing information is just one piece of SWIM. It’s actively changing how the FAA manages traffic flow, and allows users to take advantage of its monitoring capabilities.

By the end of this year, the FAA will have installed the SWIM Terminal Data Distribution System in 39 TRACONs, feeding data from over a hundred control towers under their jurisdiction. It takes local airport conditions—such as runway visual range updates and aircraft ground movement tracking via ASDE-X ground radar—and transmits them to SWIM. Subscribers, like airlines and the military, can access this data through a secure gateway to better track their planes and weather conditions.

Such was the case with JetBlue. For several years now, Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International airport has been undergoing a major runway construction project. In August 2013, JetBlue, which has a hub at KFLL, requested access to the KFLL ADSE-X ground radar data collected by SWIM and STDDS. By analyzing to-the-second aircraft taxi movements captured by STDDS, JBU was able to modify its operation around the construction, which in turn saved time and costs.

SWIM’s integration with the Corridor Integrated Weather System and Integrated Terminal Weather Systems provides a current and forecast weather picture in congested Class B airspace and predicts how it will impact ATC’s traffic flow. When weather does hit, the Reroute Data Exchange component generates rerouting options based on an airline’s preferences and presents those to controllers.

By 2015, the Flight Data Publication Service is estimated to be in operation, allowing rapid flight plan changes, predictive reroutes based on traffic flow, and 12-second active flight track updates for users—all in a global-standard data language. This allows the FAA’s NextGen systems to better communicate with other international aviation authorities.

ERAMming it Through

The National Airspace System is built around the HOST computer system. Each HOST computer—one at every ARTCC (Center)—stores and transmits flight plan data between other ARTCCs, processes radar data, and enables aircraft hand-off from one controller to another.

This is 1980’s vintage tech that’s been continually upgraded. At some point, however, patches just don’t cut it.

Enter ERAM, the En Route Automation Management system. This all-new system promises major capacity and performance enhancements that will enable controllers to coordinate more quickly, manage more flights with greater efficiency, and offer full integration with ADS-B and other new technologies.

It sounds great. Unfortunately, ERAM is four years behind schedule and hundreds of millions of dollars over budget. Originally slated for deployment in 2010, only sixteen of the twenty centers will have it running in 2014, even at reduced capability.

Part of the problem is the unique nature of every ATC facility’s airspace and traffic needs. Right now, newer ERAM installations are a buggy mess. Facilities are reporting issues as they adapt the core framework to their airspace. I’ve personally experienced aircraft not handing off to adjacent controllers, and two aircraft getting the same squawk code. To make matters worse, ADS-B, SWIM, and other new systems rely on ERAM to reach their full potential.

All in Time

Problems now don’t mean things won’t get better. NextGen’s growing pains will make the next several years rather complicated. Never a simple upgrade, it’s a full-on paradigm shift in how all air traffic information and routing is handled in the United States. All pilots, controllers, and aviation administrators will be affected in some fashion.

The 2020 target is still six years out, a generation in terms of technology. Will the FAA have everything fully in place by then? Ask again in six years. Nonetheless, visible strides are being made in all areas—ADS-B coverage, SWIM, airspace redesign, ERAM stability. With programs this complex, it’s difficult to predict just when they’ll be safely completed, but progress is real and encouraging.

Tarrance Kramer awaits NextGen with skeptical optimism while still working LastGen air traffic at a TRACON somewhere in the southeastern U.S.