Visual area penetrations have become a challenging problem for the FAA, airports and pilots. First, keeping track of them can be a moving target. Then there’s the conflict between the hazard of visual area obstacles and the safety benefit of using an advisory glidepath. Although we’ve covered various aspects of this topic in the April and July 2013 issues of IFR, recent changes could affect approaches you fly.

As evidenced by the Learjet that clipped trees at Saratoga Springs, N.Y. in 2008, penetrations of the visual area are a very real problem. Although it’s a bit unsettling to know that you’re responsible for your own obstacle clearance once you descend below minimums on a non-precision approach, that’s the way the game is played. Therefore, the more you know, the safer you’ll be.

What’s Below MDA?

The visual area consists of two TERPS surfaces stacked on top of each other. One surface has a shallow 34:1 slope, which is the height of the surface the FAA evaluates for obstacles on precision approaches. The other has a steeper 20:1 slope, equivalent to a standard three-degree glidepath or vertical descent angle. Since these are obstacle identification surfaces, not obstacle clearance surfaces, penetrations by obstructions are permitted, but result in penalties to the procedure.

Not surprisingly, aircraft are expected to be able to visually avoid obstacles in the visual area following an instrument approach, so penalties for visual area penetrations naturally involve improving visibility. If the 34:1 surface is penetrated, approach visibility is limited to no lower than 3/4 statute mile. If the 20:1 surface is penetrated, visibility is limited to no lower than one statute mile and a visual descent point will not be published. Additionally, if the penetrating objects are unlit, the procedure will not be authorized at night, although this may be waived if the runway has a visual glideslope indicator.

A problem arises when pilots—under the mistaken assumption that the derived glidepath on a non-precision approach will keep them clear of obstacles all the way to the runway—continue using that advisory glidepath below the MDA when there are 20:1 visual area penetrations. Although ILS, LPV, or LNAV/VNAV procedures do provide obstacle clearance on glidepath below minimums, non-precision approaches don’t.

Advisory glidepath guidance can be generated by some avionics systems based on the vertical descent angle (VDA) published for the procedure, which is the angle between the final approach fix at its crossing altitude and the runway at its threshold crossing height. This type of vertical guidance allows pilots to descend at a constant angle, such as with LNAV+V approaches, and provides a more stabilized approach than the traditional dive-n-drive method.

Airports Don’t Like Surprises

Airports with instrument approach procedures are typically surveyed every five years. In the interim, it’s up to the local airport management to manage tree growth. In the past, if any penetrations of the 20:1 visual area were found during periodic review of approach procedures, the procedure would immediately be restricted from night operations by NOTAM. Airports would then need to scramble to address the problem, while pilots lost the utility of the approach.

With the increased emphasis on the hazard of 20:1 visual area penetrations, more and more penetrations are being found. This is a good thing. Clipping a tree on approach will ruin your day just the same regardless of whether the airport and FAA knew it was there or not. Unfortunately, it’s also resulted in more and more surprise procedure restrictions. If you’ve ever come across a procedure suddenly NOTAMed as “NA at night,” or inexplicably annotated as such, this is probably the reason.

Early this year, the FAA implemented a new policy on what happens when it becomes aware of 20:1 visual area penetrations. The new policy provides a time frame for airport notification, response, and obstruction mitigation when penetrations are found. The time frame varies based on a risk model, with only the worst penetrations requiring immediate procedure restriction. Smaller penetrations of the 20:1 slope in the visual area still require some attention, but the response will be less severe than an immediate restriction on the approach. See the diagram to the left.

Mitigation Options

So far we’ve focused on the potential for obstacles in the 20:1 visual area, but protection can be provided by the visual glideslope indicator (VGSI). Unlike the visual areas, the obstacle clearance surface for the VGSI should not be penetrated. The VGSI surface begins at the VGSI box (about 1000 feet down the runway), while the visual area surface begins 200 feet before the runway. Thus the visual area might be penetrated by obstacles that don’t penetrate the VGSI surface.

Waivers for 20:1 visual area penetrations existing below the VGSI obstacle clearance surface have been authorized for a long time. However, they require that the VGSI be flight checked, among other requirements. Recently, the FAA has authorized temporary waivers based on VGSI with fewer requirements including not being flight checked. Additional temporary waivers exist for 20:1 visual area penetrations existing beyond full-scale lateral deflection on LPV, LP, ILS or localizer procedures. Under these waivers, procedures do not need to have penalties applied.

Another mitigation option involves evaluating multiple visual areas based on approach category. TERPS describes a wider visual area for approach categories C and D than for A and B. Previously, the visual area for the highest authorized category was used for all categories. A recent change allows the visual area for each approach category to be evaluated individually. This means we will soon see some night restrictions apply only to categories C and D, if the 20:1 visual area penetrations exist outside the category A and B visual area, but within the category C and D visual area.

You might question how waivers for 20:1 visual area penetrations could possibly constitute a safety improvement. The major step in the right direction is creating a framework for knowing that the penetrations are there in the first place. The updated visual area policy parallels recent guidance to airports for a proactive system to manage tree growth and obstructions affecting procedures. Meanwhile, the problem has been getting much-needed attention.

Trust, but Verify

A few months ago, I saw first-hand the result of misunderstanding visual area penetrations. Returning to my home airport on a rainy night, I was assigned an approach that had a note “Straight-in and Circling NA at night.” Knowing this note means there are unlit 20:1 visual area penetrations, and not wanting to stumble into them in the dark, I notified ATC that the approach was not authorized at night. To my surprise, the controller responded that there were neither chart notes nor NOTAMS indicating that.

I told the controller that the restriction is on the approach chart notes. The supervisor came on frequency and told me that the note only applied when the remote altimeter was in use (the note that followed, and was unrelated). I knew that not to be the case, so I declined the approach, and requested a procedure to a different runway.

Afterward, several local pilots recalled flying the procedure at night, never noticing the restriction. The moral is twofold. First, remember that every detail on your approach charts is there for a reason. Second, as always, trust but verify when dealing with ATC. Like the saying goes, when the pilot messes up, the pilot dies, but when the controller messes up, the pilot dies.

Lee Smith, ATP/CFII, is an aviation consultant and charter pilot in Northern Va. For more IFR nerdiness follow @LeeSmithFlies.

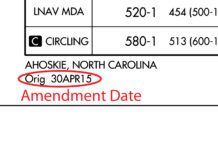

The first step taken by the FAA to mitigate the risk of following an advisory glidepath into an area with particularly hazardous visual area obstacles along the vertical descent angle was to simply remove the vertical descent angle. This is done by deleting the vertical descent angle from the approach chart and coding it as zero in the navigation database. Without a VDA, there can be no advisory glidepath indication to follow below the MDA, but this also negates the safety benefit of following it above the MDA. This has already occurred at many airports.

The presence of vertical descent angles had previously been considered an unambiguous safety benefit, and tightly integrated into procedure coding and publication. Therefore, the removal of some VDAs has caused unintended consequences. It turned out that many Garmin WAAS navigators, including the G1000 and GNS 400W/500W series, could not process an approach when the LP line of minima has a VDA coded as zero.

This resulted in approaches with a zero VDA being completely unusable at any service level, even LNAV. Garmin has since fixed this problem for the GNS 400W/500W series with the release of main software version 5.1 in February. In a related note, this update also adds support for depicting an advisory glidepath on LP approaches with a valid vertical angle (LP+V). Updates for other navigators were still outstanding as this was written. —LS