Many young aspiring pilots think that being an airline pilot is the pinnacle of the aviation profession. Maybe it is; maybe it isn’t.

But, if airline pilots are different, why are they different? Are they better pilots? No. Can they hold altitude in a steep turn better? No. Can they peg an ILS to minimums in gusty winds? No. So what is it?

Well, besides having more experience and particularly a lot of recent experience, it might boil down to airline pilots having far more resources available to them than most of us. So, the difference might just come down to effective resource management, something we all can do.

Defining Terms

The Oxford on-line dictionary defines resource as: “A stock or supply of money, materials, staff, and other assets that can be drawn on by a person or organization in order to function effectively.”

So a resource is anything that a person can use to do a job. For pilots, that can be just about anything from the aircraft itself down to the paper and pen we use to take in-flight notes. Recognize and manage those disparate resources to our maximum advantage, especially when things get challenging, and life is better.

The FAA requires that pilots who fly in Part 121 and 135 receive training in crew resource management (CRM). CRM, as a study—although originally not called that—came into existence after several airline disasters were precipitated by the captain ignoring the council of the other crewmembers.

In general aviation, few pilots have a copilot and often there isn’t even a passenger. But that doesn’t mean we have no resources to use to maximum benefit.

In general aviation, perhaps cockpit should replace crew—cockpit resource management is more accurate. That begs the question, “What resources do you, as a pilot of a general aviation aircraft, have at your disposal?” Good question.

What Are Your Resources?

You have your training and experience, and those certainly form the basis from which you manage your resources. However, in the context here, we’re talking mostly about tangible resources or outside assistance that can be employed effectively to reach a desired outcome.

The airplane systems are resources. For example, a backup vacuum pump and/or generator can be a useful resource. The airplane flight manual, checklist and weight and balance documents may be added to the list, assuming they are kept current and within reach when needed.

All of the navigation and communication avionics—whether built-in or portable—are resources you use every time you fly. Modern navigators are resource-rich, but only if you know how to use them.

Nearly anything can be a resource, but nothing is a resource until you recognize it as a such. Some items that may appear to be useless to a flight—the rubber band you have around your charts, for example—may become helpful tools if you realize that it’s a resource you might be able to employ when needed.

Here is an example of just such a situation. I was flying a Luscombe, VFR through the edge of the Dallas Class B airspace. I was in contact with DFW approach control and had been assigned an altitude, which I was carefully holding.

I was surprised when the controller called me and told me that I was two hundred feet high and requested that I maintain my assigned altitude. He gave me the current altimeter setting. I then discovered that the aircraft vibration was causing the altimeter adjustment to drift.

I was holding the altimeter knob while flying, trying to figure some way to stop the knob from moving. I noticed a rubber band around a bunch of charts. I wound the rubber band around the knob and it stopped moving. It was a crude but effective use of an unlikely resource.

As cockpit resource managers, pilots must first recognize the resources that are available. Then, it is up to you to effectively manage those resources, putting them to use to help for a successful flight.

Spot the Resources

So, let’s take a flight of fancy and see what resources are available to you. I’ll simply emphasize the resources. Your job is to see if you can recognize each item as a potential resource and in so doing, imagine a circumstance in which it might help you through a jam.

How do you plan your flight? Do you use paper charts, or maybe some automated tools.

Assume that you do your flight planning on the computer and print a hard copy of the flight plan. And as long as you are printing, you print the latest weather forecast. Be sure to check the GPS RAIM forecast for your route.

When you arrive at the aircraft, you use your flashlight to look into all of the dark recesses as you do your preflight. Of course, you’ve got spare batteries.

You’ve invited a non-pilot passenger along on the flight. You brief her on the seat belt and shoulder harness and how to open the door. As part of your pre-departure briefing, you tell her that in the event of an unscheduled off-airport arrival (Please avoid the use of the term “crash landing.”) you will need her to open the door just prior to landing and that you will tell her when to do that. Continuing the safety briefing, you show her where the fire extinguisher and first aid kit are located.

Some of you might think I’ve focused too much on a passenger safety briefing. Nope, it’s just enough. A passenger who doesn’t know what to expect or to do in an emergency can become a negative resource that contributes to the problem instead of helping with the solution.

To save the aircraft battery, you can listen to the ATIS or ASOS on your handheld radio (also with spare batteries). Since you are departing from an uncontrolled airport, you may use your cell phone to get the ATC clearance.

You write the clearance on a note pad with your pen and tune the departure frequency in the standby spot on your #1 comm radio and use the active spot for the common traffic advisory frequency. You make one last check of the enroute weather using your tablet.

Once you are in flight, you use the #2 comm radio to monitor the guard frequency and you use weather on your tablet to monitor the flight conditions along your route. To help you remain fully engaged with the flight, you also use your VHF navigation radios to cross check your GPS position.

Air Traffic Control is able to provide you with traffic and weather advisories and even ride reports.

Enroute, you might have the passenger hold the chart and follow along keeping track of where you are or use the portable GPS that’s plugged into the accessory power socket.

By now you’ve certainly gotten the idea. Those are just some of the vast array of resources available to you. The key is that you have to realize the extent of your resources and that a lot of what you take for granted can, indeed, be an important resource when you might need it.

Don’t Take Them for Granted

It’s up to you to recognize the available resources and to use those resources to help complete the flight safely. You might even find something you wouldn’t normally think of as a resource may be just what you need to help with a problem.

All of the emphasized items were resources that you probably use on every flight. Perhaps you didn’t recognize them as resources, but they are. Go back through the emphasized items and imagine how you might use that item in a pinch. Go ahead, I’ll wait…

Now that you’re trying to recognize the resources available to you, we’ve got to look at how to manage those resources. In many cases, “manage” simply means “deploy” and the simple step of recognizing something as a resource means you probably know how to deploy it, but there are other unlikely situations where a “resource” really does need managing.

Manage Those Resources

One resource we haven’t mentioned is time. Managing the use of time is probably one of the most important tasks a pilot has to undertake.

With regard to managing time, there is one prime directive. Never get in a hurry, because if you get in a hurry, you are going to make a mistake. In fact, it’s often best to slow down to get more done, more quickly and more effectively.

So, if you feel someone or something trying to make you rush, and especially if you’re starting to feel the stress of that time pressure, deliberately slow down. Methodically complete all of your tasks, checklists, and procedures, carefully using your other resources. It is a lot easier to take your time and complete all of the required procedures than it is to try to explain why you made a mistake to an examiner—or an accident investigator.

Use your time wisely. For example, when do you load the route in the GPS navigator? If you are fairly certain that ATC will assign you the requested route, you may want to program the navigator as soon as the engine is providing electrical power.

However if your departure or route is changed by ATC, pull over to the side of the taxiway, stop the aircraft, set the brake, and reload the cleared route. Do not go ahead and take off, thinking you can make the changes in the air. Ask yourself, “How would that sound at the hearing?”

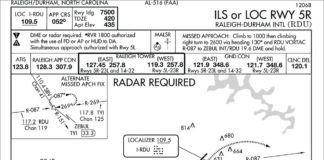

If the departure is RNAV, are there back up VOR/DME fixes available? If so, tune the frequency and set the CDI to show the radial. Countless reports have been filed by pilots who thought a departure was properly programmed into the navigator, only shortly after takeoff to wonder why they weren’t getting a turn. It is very reassuring to have VOR cross checks set up prior to departure.

On departure, you manage the navigation resources by keeping close track of your position and making sure that you fly the clearance, and not the flight plan, in case of a route change by ATC.

ATC is a resource that often needs managing. Hold the snide comments, please, I’m not trying to make a joke. Consider descents for approach. If you don’t get the descent at a time you need for proper aircraft management, ask. If denied, simply tell the controller you’ll need a specific amount of time for your descent “for operational requirements.” You’ll get it, either with a descent clearance or a delay vector.

Another example of managing the ATC resource is any time you have even momentary navigation glitches. Say you were just cleared for a different approach than what you expected. Simply ask for further vectors while you get things set up. Or, say you’re given an uncharted hold with little notice. You could simply ask for vectors to enter the hold as you figure it out.

If you have a passenger, the passenger can be of help by simply listening for your call sign on the radio. How many times have you heard ATC making repeated calls to an aircraft and when the aircraft finally answers, it is apparent that the pilot was either not paying attention or was distracted by some other task.

Managing your navigation resources might include an accuracy check of the GPS, by using the VOR receiver to fly directly over a VOR and confirming that the published coordinates match those displayed on the GPS navigator.

You can manage your fuel resources by proper leaning and monitoring fuel flow for best speed, range or endurance, depending on the needs of your flight. Don’t be afraid to switch from one to another at a moment’s notice, too, especially if you’ve been blasting toward your destination, assuming safe fuel when you get there, and suddenly find that it’s closed due to an accident. Slow to best range immediately so you can make an alternate with ease. Manage your resources.

Just Do It

You don’t have to be an airline pilot to take advantage of good CRM. All you have to do is recognize your resources and use them to your benefit.

So, the next time you fly, take a good look at the things that you have in your aircraft. Then be prepared to think “outside the box” if you find yourself in a situation that requires creative problem solutions.

And if you do that, you can take satisfaction in the knowledge that you are practicing good CRM, just like the crewmembers in the airliners above you.

George Shanks retired from a major U.S. airline and now teaches for a corporate pilot training center in Dallas, Texas. He always has a supply of rubber bands at hand.