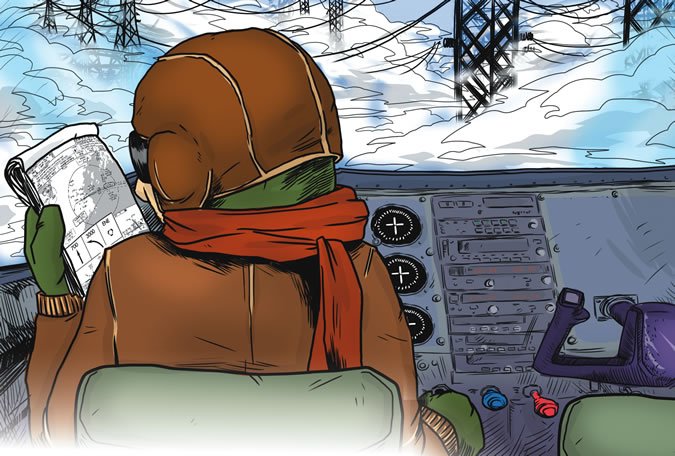

Art by Ben Bishop

As an instructor for GLASS Simulator Center in Sugar Grove, Ill., I see a lot of pilots execute missed-approaches. They’re all instrument-rated and flying the sims for type-specific aircraft training. Most have considerable IFR experience.

Here’s the shocker: More than 80 percent of these pilots make potentially fatal errors while executing their missed-approaches. I remember watching one pilot make random, 360-degree turns after pulling up. Another continued straight (when the missed-approach procedure called for a climbing turn), climbed to a random altitude and just drove around the sky. Neither pilot had a clue as to what he should be doing.

When I asked them what went wrong, they both gave approximately the same answer: “I didn’t know what the missed-approach procedure was and I got disoriented and confused.”

Commonplace Catastrophes

A common theme is pilots not immediately getting the aircraft moving away from terra firma in a positive and purposeful manner. Components of this error include not applying go-around power, not pitching up to go-around attitude, pitching up way beyond go-around attitude, not properly configuring the aircraft for the go-around and not climbing out at the recommended airspeed. I have even observed a few pilots lose control of the aircraft and freeze the sim as they stall and spin in.

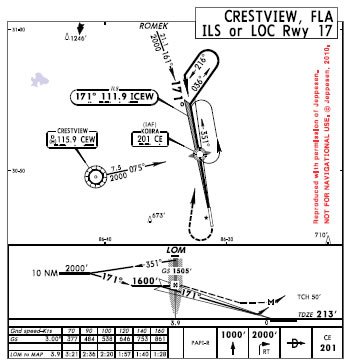

I’ve seen many pilots descend well below DA on an ILS approach or stay at the MDA way past the MAP before executing a missed approach. Many, many pilots misuse the GPS moving map on missed approaches by simply following the direct line from the airport to the missed-approach-holding point (MAHP) instead of flying the required climbs and turns before heading to the MAHP as published.

Another disturbing habit that most pilots seem to have is looking down at the approach plate when approaching minimums or while trying to execute the first steps in the missed-approach procedure. They inevitably depart the missed-approach profile, sometimes disastrously so.

Some tell me they didn’t expect to fly the missed approach and weren’t prepared. Others tell me that they never have to make missed approaches in the real world, and if they did, ATC would give them a straight-out climb. A few even claim that they performed poorly because I unfairly made them go around when they weren’t expecting it.

Digging in the AOPA Air Safety Foundation stats, I found that from 2003 through 2007, 20 accidents in fixed-wing aircraft of 12,500 pounds or less occurred either during missed approaches or because the pilot failed to execute a missed approach after passing the MAP in actual IMC. Of those, 17 out of 20 (85 percent) were fatal, killing a total of 39.

In my opinion, an instrument-rated pilot who cannot consistently and proficiently execute a published missed-approach procedure should not be flying in IMC conditions. Yet, the FARs allow a pilot to do so: Missed approaches are not required to be logged to maintain instrument currency. But you can do better than so many of the pilots I see by following three simple steps: preparation, anticipation and execution.

Your Ducks in Rows

Preparation for a missed approach should be done well before beginning the approach, as part of the approach briefing. You can’t simply glance at the missed-approach icons in the profile view. Critical missed-approach information may be in the details provided in the textual description or clarity may be found by walking through the visuals of the missed on the plan view.

Set up your primary and back-up navigation equipment for the missed approach as much as possible. Don’t rely on the GPS moving map for the course to be flown from the missed-approach point to the holding fix. In many cases you must fly to the holding fix on a particular heading combined with a VOR radial or other non-GPS course, for obstacle clearance or other reasons. Also, by setting up back-up navigation equipment, you will be prepared in case you lose GPS capability or somehow program it incorrectly.

You might also consider that GPS failure or integrity errors on a GPS approach require you to start your missed approach but simultaneously mean you can’t use the GPS for that missed. Sometimes there is a holding fix that can be identified using conventional navigation. At least it’s worth considering.

This touches on a larger concept of having an “A” and “B” plan for flying the missed. For example, your “A” plan may be to fly the missed approach using your GPS and your “B” plan may be to use your backup navigational equipment. Or your “A” plan may be to request an alternate missed-approach procedure from ATC before you start the approach that better sets you up for heading to an alternate airport, and your “B” plan may be to fly the published missed-approach procedure.

This is even more important with a circle-to-land, where you may be starting a missed from a point a mile or two off the published procedure and heading in a different direction. You must have a plan for this missed approach ready to go, including which way to turn and how high you must climb to get back onto a published procedure of some kind.

Continuing that thread, you want a plan before you start the approach for what you are going to do after a missed approach has been executed: Go to an alternate, try another approach or hold and wait for weather to improve. Make sure you know what you’re going to do before you start the approach and take all pertinent factors into account (for example, current and trend weather, fuel on board, fuel required to execute your plan, traffic, fatigue, etc.).

Memorize (or better yet post near the attitude indicator on a sticky note) the first critical MAP steps. You must be able to execute the missed-approach steps as depicted by those missed approach icons without looking down at the approach plate on short final or at the moment you decide to go missed.

Spring-Loaded

Anticipation is the second key to successfully executing a safe and compliant missed-approach. It’s the easiest element to master. Simply always assume that you are going to have to fly the published missed. Think of your prepared missed approach being armed and ready on every instrument approach no matter the weather or traffic situation. If you break out and land, that’s a bonus.

There are many things that can cause you to make a missed approach, reaching minimums with no runway in sight is only one of them. A disabled aircraft or wildlife on the runway could be another. How about flying an ILS you know will be right to mins and you get a message from your Garmin GNS 430 that says, “G/S not responding”? Does G/S mean glideslope? It seems to be working as you follow it downhill, but is it really OK? Are you going to pull out your Garmin manual and look up that error message as you descend for DA?

Make it So

Execution is the final, key element. When you make the decision to miss the approach, there are five steps to make it happen: Power-up, pitch-up, clean-up, navigate and communicate.

Step one is to smoothly apply takeoff power. Most pilots seem to do this one OK. While applying takeoff power, you should simultaneously pitch up to the proper go-around attitude for the aircraft and keep it there. Failure to pitch up, or initially pitching up but then letting the attitude decay, is a common error. Don’t let the nose rotate skyward into an attitude that will result in a stall, either.

“Cleaning up” means reconfiguring the aircraft. This could include raising the gear and flaps, and opening cowl flaps. “Navigating” is flying the published procedure, which includes reconfiguring your navigation radios/GPS (see sidebar on page 7). “Communicating” is announcing your missed approach to Tower/CTAF and checking back on with Approach or Center. Give ATC the reason for missing the approach and your intentions.

The only way to stay proficient at missed approaches is to practice. This means that you must fly, in my opinion, at least four missed-approach procedures (and not just the straight-out type) every six months.

We all know that’s unlikely in any real-world situation. You could fly for a year and not fly one missed approach out of necessity. You could do these missed approaches with a safety pilot, but this is expensive and in the real world ATC may not be able to let you fly the complete published missed-approach procedure.

In my opinion, the absolutely best way to maintain your IFR proficiency in general, and your ability to make safe and compliant missed approaches in particular, is by using a good flight training device or other simulator. A half-day session will fulfill the requirements for instrument currency prescribed in FAR 61.57, and you’ll be able to practice far more involved (or sinister) emergencies and abnormal situations with a full missed-approach procedure each time. I think it’s the most effective (in terms of time, money, safety and efficacy) approach to maintaining your IFR proficiency.

A Missed Opportunity

Maintaining your status as a safe, competent and proficient IFR pilot is your responsibility. It cannot be accomplished through wishful thinking, overconfidence or a false sense of security. You must put in the requisite work to keep you and your passengers safe. Do you want to be part of the unfortunate majority I see who do fine until they get hit with an unexpected missed, or do you want the reward of turning a surprise in demanding weather be just another part of instrument flying? It’s up to you.

David C. Koch has been an instructor since 1965 and holds an ATP with over 18,000 hours.