Dave strolls into the FBO carrying a travel bag and a pizza box. I let out a sigh. “Well, look who showed up. Dave, you’re 45 minutes late.”

“Well, I needed gas, and there was a pizza place next door and, well, that smell hit me. I got some for everybody.”

“We’re already late and we need to get going. Let’s eat in the air.”

You, Dave and I head outside into the muggy Florida air to our Mooney. We stow our bags and I begin the preflight. Dave piles into the back. After the preflight you follow me in and close the door as I grab the checklist.

“Do you mind calling for our clearance?” I ask, reaching for the master.

“You got it,” you reply. You have our XM Weather system set up. We’ll need it today. You grab our paperwork and get our clearance. We’ll be flying from Orlando Executive up to the Panhandle, then west across Pensacola to the New Orleans area. We’ll land at Slidell—we heard good things about the FBO and the fuel is cheap. We’ll also get the scenic half-hour drive to New Orleans.

The engine roars to life and we’re soon headed to the runup area. Since about 40 miles of our flight is over the ocean, I’m careful with the runup.

We call the tower for takeoff clearance, amble into position and open the throttle. The takeoff is smooth and we climb westward into a hazy sky. Orlando Departure turns us toward the Florida Panhandle. The smell of pizza is tantalizing and I’m looking forward to cruise.

Weather Ahead

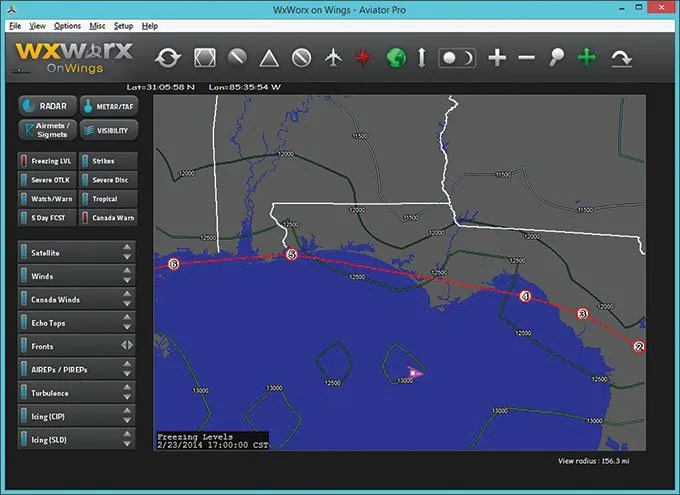

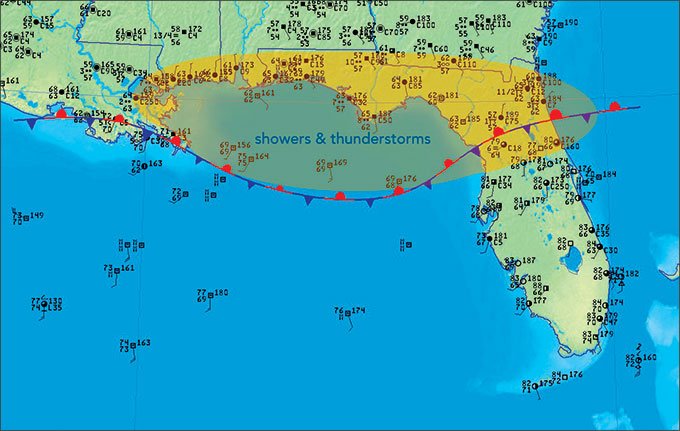

During our weather briefing, we saw an area of showers and thunderstorms in the western Panhandle. It extends north into Alabama and Georgia, so we can’t really go around it. The freezing level (Figure 1) is quite high, at about 12,000 feet. Ice shouldn’t be a factor at our 6000-foot cruise. We’re most concerned about the storms and widespread IMC. Plus, it’s February, so the atmosphere might have a few surprises we’ll watch for.

Though looking at SIGMETs and getting a weather briefing gives us the basics information we need, there’s not a lot of deptch. What if the forecast is wrong? We can get an extra safety margin by taking in the big picture. By understanding the underlying workings of the atmosphere today, we’ll have a comprehensive picture of the patterns.

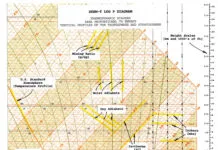

The surface map (Figure 2) shows observed conditions over the Gulf Coast. The pressure field is too weak for a meaningful isobar chart, but observing the temperature field and hand-drawing the front (as shown) reveals the definite presence of a quasi-stationary front extending from northern Florida to Louisiana.

What does this front mean? If we look at conditions in the warm sector to the south, we see there is a component that crosses the front from south to north. Forecasters will conclude that the isentropic (potential temperature) surface distorts upward in the cold air mass and parcels must ascend along these surfaces since potential temperature is a conserved property. But it’s simpler to think that this air tends to rise as it “overruns” a warm front toward cooler air.

The south-to-north component will also cause the front to drift northward as a warm front, but this is often offset if there is an opposing north-to-south component in the cold air mass or extensive cold outflow from thunderstorms. There are widespread storms all along the front, so we can’t really be sure which way the front is moving. It will be difficult to know what changes will be occurring at a terminal near the front, so we have to depend entirely on the TAF.

The air mass in the Gulf Coast region is unstable and it doesn’t take much lift to produce showers and thunderstorms. Frontal lift is significant, yielding widespread IFR conditions and an outbreak of showers and thunderstorms. We can expect conditions south of the front to remain good if it is a stagnant tropical air mass with VMC and cumulus at 2000 to 4000 feet. If this air mass is modifying, shallow stratus and fog might develop.

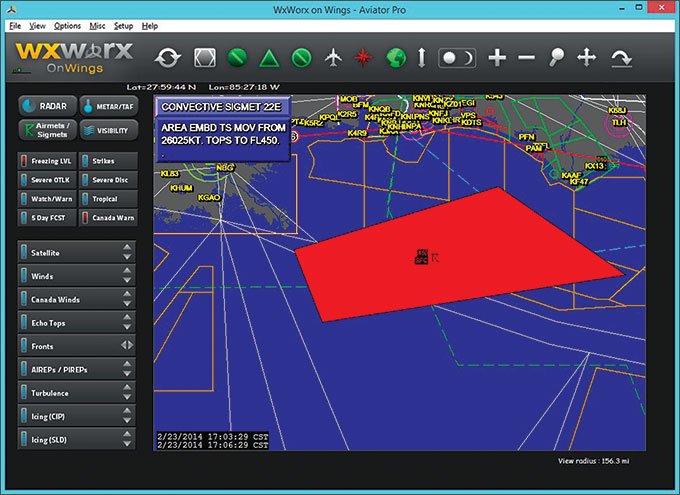

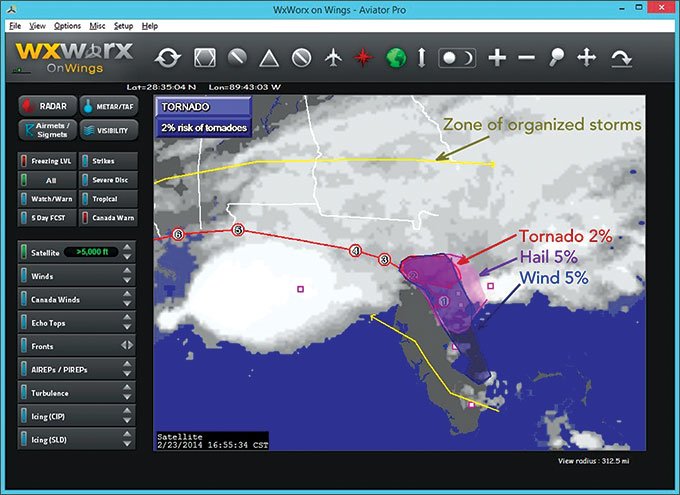

SIGMET and AIRMET products (Figure 3) are definitive for weather hazards of concern to pilots. These are produced by the Aviation Weather Center. The only downside is that they don’t provide any indication of severity. The Severe product (Figure 4) is a nice supplement that gives an accurate overview of the hazards. This data originates directly from the Storm Prediction Center convective outlooks. Although the SIGMETs and AIRMETs are already part of your preflight planning, checking all these products during a cross-country flight will help alert you to any changes in forecast thinking.

Cruising Along

I engage the autopilot as we level off at cruise. The view is occasionally obscured by clouds, but I can see Lake Apopka off to our left and endless subdivisions, probably Orlando’s bedroom communities. I strain to look toward the southwest, but Disneyworld is too far away and there are too many clouds. It’s a little bumpy.

The smell of pizza is overwhelming. I turn back to Dave. “Let’s open that pizza.”

“Yeah,” Dave says. “It’s right here.”

He opens the box. Something isn’t right. I take a close look at the pizza.

“Anchovies? Pineapple? Daaaave?”

“Hey man, don’t knock it. I like anchovies with pineapple.”

This must be payback for last week when I actually got him with the old prop wash prank.

I grab a shop towel and take a slice of the pizza. I pick off the anchovies. The pineapple I can deal with.

You pass on the pizza and settle back into the seat, watching for traffic and enjoying the view. You notice that things are getting a bit dark up ahead. “I think I’d like to take a look at the weather.”

“I was thinking the same thing.”

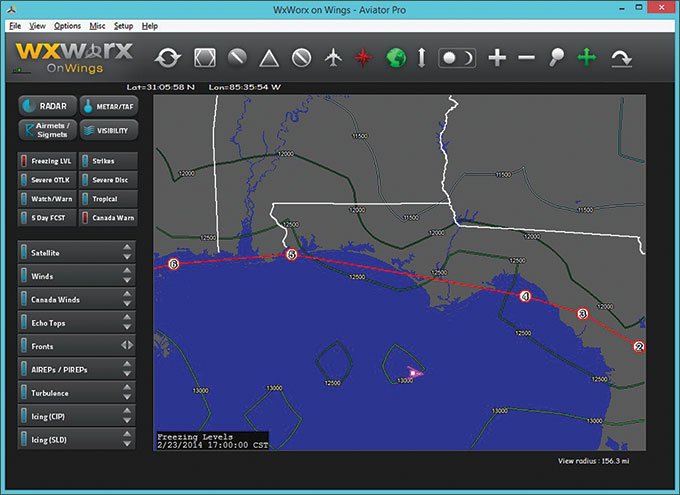

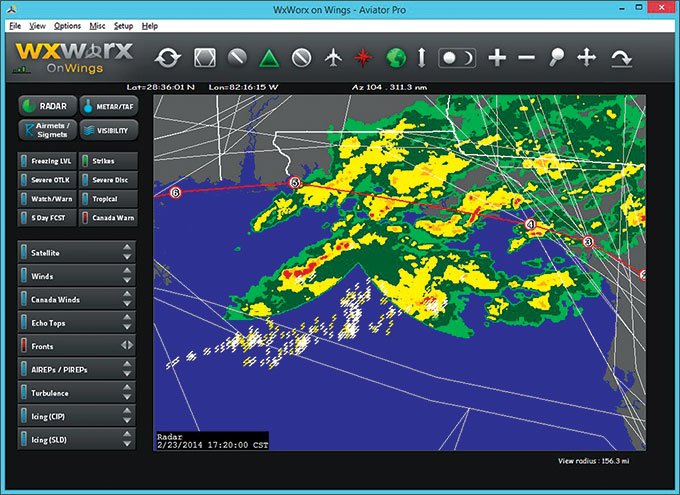

You select the METAR, Radar, and Strike products (Figure 5). We see an area of showers ahead. The Strike product shows no lightning activity ahead. The image is built from a radio sferics network, covering the United States and reaching far offshore, and it accurately detects cloud-to-ground lightning.

The bad stuff is well off the coast, where the Strike product shows clusters of lightning. Radar doesn’t reach that far. This shows the value of the Strike product deep into the Gulf of Mexico or off the Pacific or Atlantic coasts. The U.S. has four other areas out of radar range: central Nevada, the Four Corners, southeast Montana, and south-central Oregon where the Strike product proves invaluable, especially during the summer.

As we hit the showers we get bounced around a bit. A few small areas show red, and we deviate well around them. Over Apalachee Bay I open the vent window and pitch the anchovies. While I’m at it, a little rain blows in and hits Dave. I smile.

We bounce in and out of showers, break into VMC and enter another mass of clouds and showers. We reach land and count down the miles to Pensacola.

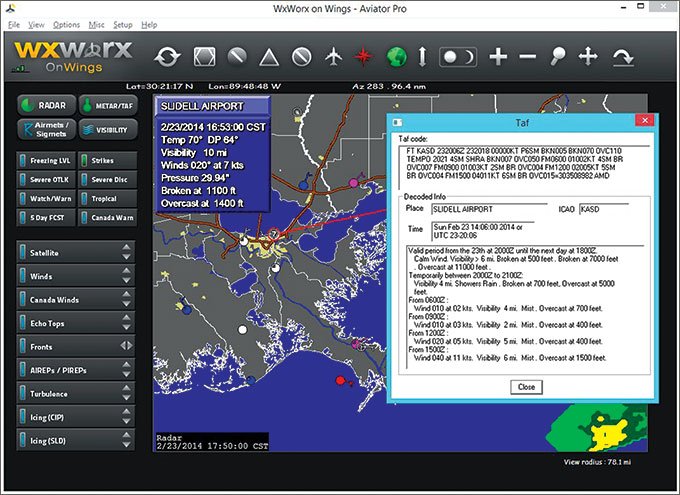

“How is the weather looking at Slidell?” You switch back to the Metar display and pull up Slidell METAR and TAF reports (Figure 6).

“Still IFR,” you say. “It’s 1100 broken, but 10 miles, not bad. Looks like 500 broken and 6 miles forecast. We’ll be getting there after that TEMPO group.”

Gentleman’s IMC

The rain clears up but it remains cloudy. Daylight fades and the overcast darkens into night. Starting down past Gulfport, we descend through several cloud layers created by the gentle lift over the frontal surface, condensing humid air from the Gulf waters and producing extensive stratus. We fly the GPS Runway 36 approach and break out of the clouds at 800 feet. We have the runway in sight almost immediately. We land in light winds.

We park, close our flight plan and shut everything down. I notice the sweep of the airport beacon against the clouds. That’s the tropical air mass just overhead. The temperature is a mild 67 degrees with a light north wind; down here we are in a shallow, stagnant polar air mass.

“Time for some real food,” you say.

“Yeah.” I look at Dave. “We’re going to the Crescent Pie. We shall crack open some Sessions and feast on jambalaya, reveling in New Orleans. Maybe we’ll hit the French Quarter later. Anchovies and pineapple will not be part of this night.”

Dave sheepishly nods. “You think they have any hot wings there?”

We laugh as we get our rental car and pitch the remaining pizza.

Tim Vasquez is a professional meteorologist in Norman, Oklahoma. XMWX satellite weather is available on many devices and apps, and each adds their own interpretation. For this series, Tim uses WxWorx on Wings, a PC application from the data provider for XMWX. See his website at weathergraphics.com