Every airport with an instrument approach must have some blessed IFR departure. But that doesn’t mean you can fly it, and the problem might not be climb rate.

On a fine spring day, you trundled off to Driggs, Idaho, to meet your buddy and sneak off to the best-kept-secret fishing spot in the west Tetons. Your buddy made a killing because he was an Apple geek in the ’80s and bought no stock but theirs. He chartered a plane to Driggs. You invested heavily in the DeLorean Motor Company—and arrived in your dad’s old 172H.

Your mind was on cutthroat rather than prog charts when you flew in. On departure day, you’re under 800-foot ceilings with visibilities of a mile in light rain. This is no problem for a proficient IFR flier like yourself. Driggs may be nestled between two mountain ranges, but it’s got a published instrument approach. Given that those mountains rise from 3000 to 6000 feet higher than Driggs in all directions but northwest, there’s bound to be a published obstacle departure procedure.

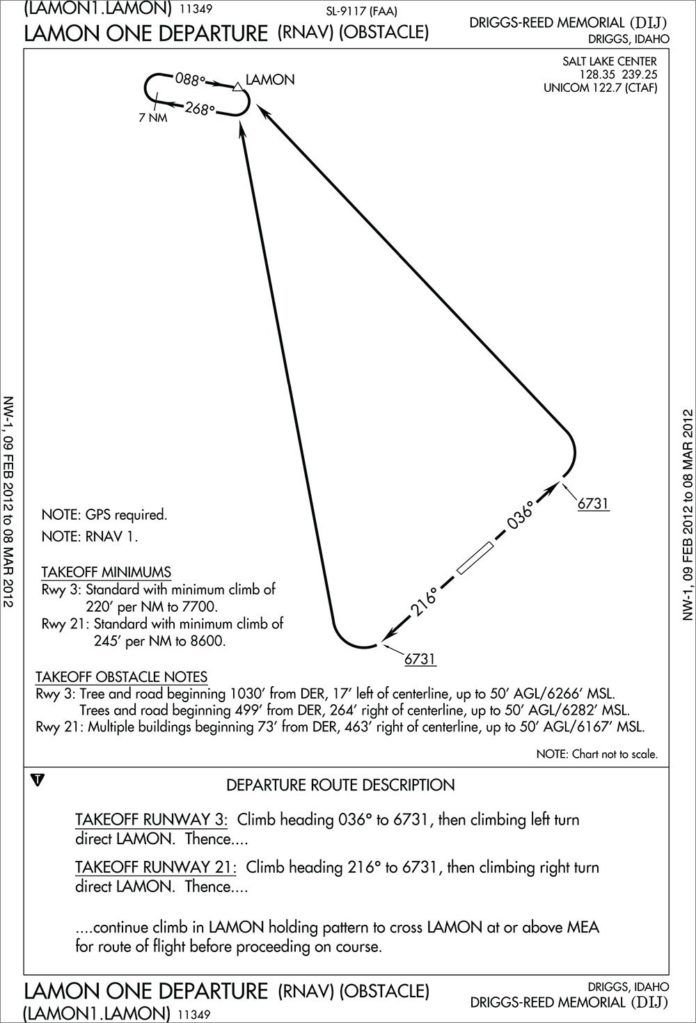

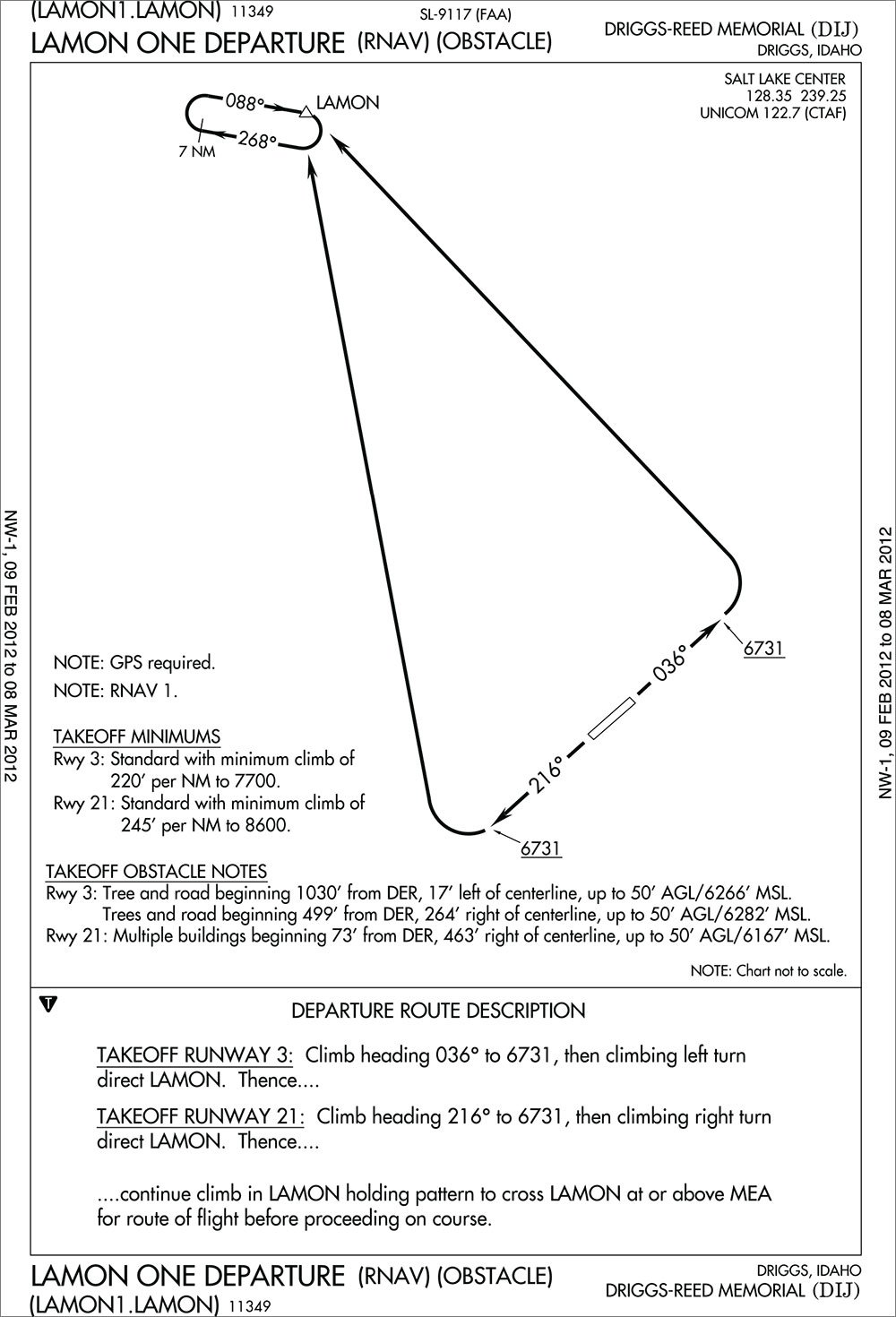

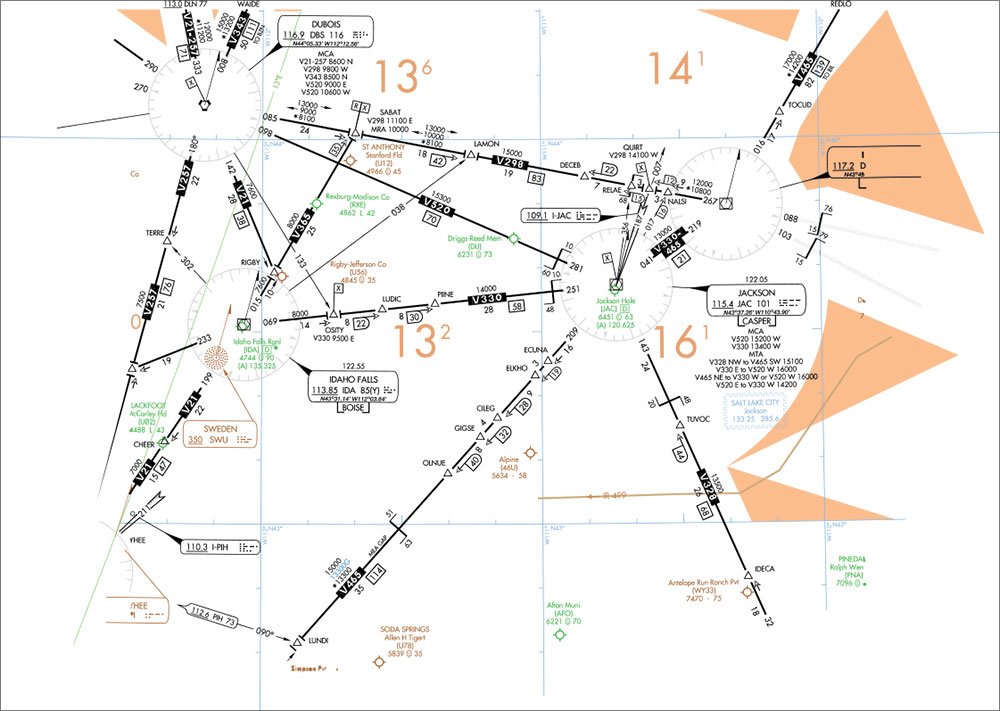

Sure enough, there is, but—surprise—it says to fly the LAMON ONE departure, and that procedure requires RNAV. The vintage Cessna has equally vintage nav/coms and a Garmin 196 monochrome unit duct-taped to the yoke. Now what? Can you leave, or are you stuck fishing until the weather clears? (Hey, this could be the most fun no-go decision ever …)

Here’s where legal is mildly murky and smart is a matter of strong opinions. On the legal side, there’s no obligation under Part 91 to fly any published departure procedure when launching from an airport into the murk. It’s a really good idea, but not mandatory. So the fact that you don’t have RNAV doesn’t preclude you from departing Driggs IFR.

If you don’t fly the published procedure, you’re on your own to figure out a way to get from the pavement up to your cleared route, which we’ll say starts at the same LAMON intersection on V298. That’s going to be tough without GPS. You’re out of the service volume for any nearby VOR and can’t even guarantee reception of LAMON until 10,000 feet. You’ll be climbing for almost 4000 feet northwest-bound in the blind, hoping your estimates on wind drift were good enough, and you get reception of the Dubois VOR before you pass north of V298.

Except that you have the 196 portable—and a conundrum. What happens if you officially decline the LAMON ONE as part of your clearance, but then fly it with your portable “as verification that you’re staying clear of terrain”?

ou could legally attempt to dead-reckon the course of the LAMON ONE and break no reg other than common sense (or maybe FAR 91.13 Careless and Reckless). Or you could fly the course of the LAMON ONE with your portable, but find yourself in the legal miasma of flying a GPS route with improper equipment. But if it’s legal without it, how could the unquestionably safer flying of the route with the portable not be legal?

Perhaps there’s some clarity in the “what-if” game, such as what if your GPS reception, or that device, Murphys out 30 seconds after you’re in the soup? The only approach back into Driggs is also an RNAV approach. GPS failure necessitates dead reckoning to V298 again. How does that feel?

If it feels OK, then we can’t think of a legal barrier to your departure. This presumes that you’ve got sufficient climb to make the 220 feet/mile to 7700 feet and cross LAMON at 10,000. If you drank all the beer while you caught and released and the only weight in your Cessna is a fly rod and a sleeping bag, that might be true. And if the GPS is golden but you can’t make it to 10,000, you could use the GPS to get you along the airways at 8100 feet until you get on V365. But now you’re squarely in violation for using your portable GPS for IFR navigation. There was a time when the FAA was a bit lax about that sort of thing. Now they are quite clear that if you get caught, there will be consequences.

Consequences, actually, is probably the watchword for this entire scenario. If hacking the departure, with or without a portable, works and you survive the trip to LAMON, no one will know or care. (In other words, you can be reckless so long as you’re wreckless.) If you don’t reach LAMON as planned, they can mail the certificate-action letter to your next of kin.

Your buddy who still has a commemorative shrine to Steve Jobs doesn’t get the same choice, however. His chartered King Air came in the night before and also doesn’t have GPS. They could easily climb northwestbound and top even the mountains. But they’re under Part 135 and without some FAA-blessed agreement otherwise, can’t skip the official LAMON ONE.

Maybe it’s time to just go back to the creek.