Different Spins on TAAs

Your editorial in the May issue, “Looking for Eight More Lives,” quoting from the Air Safety Institute’s 2012 TAA Special Report, provides an example of how easily summary statistics can lead us astray. Different reports use different methodologies.

By grouping Cirrus and Columbia together, the ASI report implies that Columbia aircraft suffer from a relatively high rate of stall/spin accidents, yet in the entire history of the Columbia fleet, there has been only one documented stall/spin accident. Since the Cirrus fleet is larger and started shipping earlier, the ASI grouping is biased almost 10 to 1 by the Cirrus accident history.

A January 2012 Aviation Consumer article looks at the numbers from a different angle. It reports that Columbia aircraft have lower total and fatal accident rates than GA overall. Moreover, the percentage of Columbia accidents that are fatal (26 percent) is dramatically lower than for Cirrus (48 percent).

Instead of lumping the two fleets together and assuming they have the same problems, I think it is much more instructive to ask why their accident histories are so different, given the aircraft are so similar.

Between Cirrus and Columbia, there are numerous differences in procedure, training and performance. For example, we are taught to fly a Cirrus downwind at Vy—the edge of the region of reverse command, whereas the Columbia procedure is to fly downwind at roughly Vy+15, which allows for better altitude control in the pattern. We practice a standard complement of power on/off stall recoveries during a Cirrus transition, whereas the Columbia transition requires no fewer than 15 full-break stall recoveries in all configurations and attitudes.

Perhaps most relevant to the stall/spin statistics, a number of Cirrus accidents occurred during training when pilots were practicing the “impossible turn,” a 45-degree banked return-to-field at best glide. In an SR22, that puts you only seven knots above stalling speed, whereas in a Columbia, it’s 27 knots above stalling speed. In response to a spate of these accidents, COPA is now actively promoting the “CAPS NOW/CONSIDER CAPS” safety briefing prior to takeoff.

Any or all of these factors may have impacted the accident history, and I think it behooves us not to paint “TAA” with too broad of a brush. Instead, let’s look more closely at each fleet and keep working to improve how pilots fly—as your magazine does so well. Better procedures and training can be just as effective as additional bells and whistles, if not more so.

Thank you for another great edition of IFR.

Peter King

Bend, Ore.

FSS Agreement

I am writing to compliment you on “Where is FS21?” (May 2012 IFR), which I just finished reading. It is spot on. The problems reported with getting clearances at remote airports, specialists bogged down in disseminating unneeded information especially when the pilot needs to be doing something other than listening to it, and rarely providing PIREPs so as not to get bogged down in the process mirror my own experience. I also agree that there are some great folks in FSS. If I experience ambiguities or concerns, there is a good chance they will be resolved by contacting a specialist. But that doesn’t mean there need not be changes.

I assume you’ve had your meeting with LM and the FAA by now. I hope they agree that at the least some paradigm tweaking is necessary, if not a complete paradigm shift.

Please keep up the great work.

Gabe Buntzman

Bowling Green, Ky.

Their reply is on page nine. It explains a few things, but offers little hope for these particular problems.

On VASI and Into the Weeds

Always love your magazine. With regard to your article, “The Right Time to Descend” (March 2012 IFR): If you are on the VASI glideslope and have the VASI in sight, how can terrain bite you?

Adam Carney

Middletown, N.J.

Many people don’t realize it, but the VASI only guarantees obstacle clearance four miles from the runway. Past that point, you could be on the glidepath looking at the VASI between the wires of a cable crossing or the branches of trees. It would be obvious in the daytime; not so much at night.

Dueling Localizers

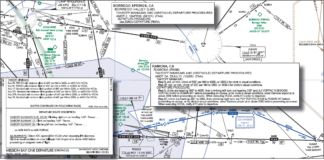

Because I often fly into Boeing Field (KBFI), I recently practiced the ILS Rwy 13R on my On Top computer-based simulator. Using its HSI configuration, I found that when I was on the missed on the southeast course, as published, there was reversed sensing with the HSI still set on the front course of 130 degrees. Resetting HSI to 310 produced the correct sensing.

This is confusing to me. Then I noted that there is an ILS 31L to Boeing on the same frequency, but with a different identifier. Obviously being on the missed-approach course, you are at the same time on the front course for the ILS Runway 31L.

How would you know this flying in, unless as part of the briefing, you looked at all the approaches to the airport?

Charles Tannenbaum

Springfield, Ore.

This is an artifact (error) of the simulator, where it treats ILSs to opposing runways as simultaneously active. Many airports have opposing ILSs on the same frequency, but only one is on at a time. In the real world, you’d leave your HSI set for the front course right through the missed and have correct sensing throughout.

Reading Someone Else’s Bible

I get a lot out of your publication and I enjoyed the very informative article on the fact that ATC and pilots are not always operating from the same rules book (“Straight to the Middle.” May 2012 IFR). This is not the first time ATC has had a different concept of procedures compared to what we follow from the FARs and AIM. Although it is constantly stated that the AIM is not regulatory, from the FAA perspective it is often interpreted that the AIM is regulatory in certain cases.

But many of us who learned all the FARs and AIM advice concerning IFR operations were never introduced nor encouraged to read the ATC bible, the 7110.65.

I was taught that was “only for controllers.” Given the fact that this is the second article now in the past few issues that depict controllers having a different view of things, it probably behooves all of us pilots to read that manual so we at least know what the controllers are expecting.

Looking forward to seeing the FAA get the FARs, AIM and 7110.65 more in tune with each other in the future.

Brian Turrisi

Potomac, Md.

No pilot is obligated to read the 7110.65. It’s not exactly a compelling text. But when there seems to be confusion or misunderstanding, it’s helpful to see how the other side of the mic views the situation. What a controller is required or not required to do is “not your problem,” except for the fact that it’s your hiney barreling through the clouds in that aircraft, not theirs.

Reach us at [email protected].