Until 2004, Flight Service conducted most preflight briefings. Then self-briefing arrived. By 2017, 96 percent of all pilots self-briefed and 83 percent of flight plans were filed online.

But many of us don’t know how to get a thorough self-briefing. Between 2010 and 2013, the NTSB could find not weather briefing records in 32 percent of 5437 accidents. Consequently, the FAA is strongly stressing self-briefing, so it’s time we explored how we might do that.

![NEXTGEN_View_Benefits_[Table]processed](https://s30382.pcdn.co/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/p1dgtsqaetjuq9e01iv44vf15eb6.jpg.optimal.jpg)

What Is a “Legal” Briefing?

There is no such thing. Part 91.103 makes no mention of a weather briefing. It casts a wider net to include “all available information concerning that flight.” This includes, “for an IFR flight or a flight not in the vicinity of the airport, weather reports and forecasts.” This is far from a well-executed standard briefing.

The FAA considers the weather requirement met if the pilot gets a standard briefing within two hours of departure, then an abbreviated briefing thirty minutes before departure if the weather is questionable. Gaining a good idea of the big picture, a feel for trends, and all supporting weather reports is enough to make the go/no-go decision.

But a standard brief alone does not satisfy 91.103. If IFR or flying outside the airport vicinity, we are expected to also know fuel requirements, alternates if the planned flight cannot be completed, and any traffic delays advised by ATC. We must know the runway lengths, including takeoff and landing distance data if an Airplane Flight Manual exists. Else, we are told to make do using “other reliable information appropriate to the aircraft” including aircraft performance.

The reg never contemplated a situation where today’s abundance of information could lead to less knowledge. Be suspicious. When weather reports abound, confirmation bias might sway us toward choosing the rosiest one when the more conservative report is the wiser choice. The more doubtful or contradictory the weather forecast, the more information you need to obtain.

CYA

When pilots ask about a legal briefing, often they are really asking if a record was kept of the brief. If you must log in, there is most likely a record. Briefings at 1800WxBrief.com are retained for 15 days in your account. Calls to FSS are recorded and kept for 45 days.

Prying information from the FAA can be difficult, and retention is short. Save or print your briefings. If the FAA asks, you can prove that you briefed.

No certified weather sources exist other than 1800WxBrief.com since the certification program itself was scrubbed in 2013. Many other services meet the old official performance criteria anyway, and you could make a case that they’re sufficient if not official.

Pre-Brief Preparation

A flow is one way to avoid taking in either too little or too much information. That flow is: lows, fronts, and upper air analysis.

Start with the big picture and work down. Check out weather products from TV and online providers. Develop an overall mental picture of current and forecast weather. Lows come first because they are weather-makers responsible for much of the bad weather. If the low is strengthening, expect worsening weather and vice versa.

Where are the fronts? Fronts show up clearly on prognostic charts and are just beneath lows in terms of weather-making. Fast-moving cold fronts spilling over into warm, moist air trigger thunderstorms. Fronts can move quickly. They may be distant or cross your route by the time you fly.

Upper-air winds drive the weather-makers’ direction. The 500 millibar chart (about 18,000 feet) offers a clear view of where and how fast a weather system is moving. Look for troughs and ridges and how strong a low might be.

The next step is to absorb the information to understand what it means to your proposed flight. Weather affects pilots in three ways: reduced visibility, turbulence, and diminished aircraft performance. Look for anything that will or might adversely affect your flight. Additional tools that might help are surface analysis charts, national forecasts, radar/satellite images (but alone they are insufficient), and local observations. FIS-B does not replace a prefight briefing!

Request an Outlook Briefing when your proposed departure time is six hours or more from the time of the briefing. You will receive forecast data valid solely for planning.

Briefing Basics

There are three types of weather reports: observations, analyses, and forecasts. Know which kind you’re looking at.

Learn cloud types because they hint at the weather. Cumulus clouds imply unstable air. Stratiform clouds imply stable air. Nimbus clouds contain rain. Don’t let these clues escape you.

Only TAFs, METARs and AIRMETs use AGL altitudes. All others such as clouds are MSL. Know the various SIGMET and AIRMET types and the conditions under which they are issued. Just because neither is present does not imply the absence of bad weather. Given the choice, good visibility beats a high ceiling.

Learn the basics of ICAO notation used in weather reporting. Its notation is more precise and often preferred over plain-language translations.

Getting a Standard Briefing

For this article, we’ll use the Leidos Flight Service site, 1800WxBrief.com. It is easy and intuitive. Create a free account to unlock its features. Its Pilot History page saves up to 15 days of pilot history events. It might be helpful to follow along as we walk through the site.

Once logged in, the Pilot Dashboard page shows four charts by default: Weather Depiction, Surface Analysis, the 12-hour Surface Prognostic and the CONUS Radar Summary. Review these to get the big picture of what’s going on. A lot of customization of the presentations is available, so don’t be afraid to experiment.

Note that many of the items available on the top menu bar offer additional variations when you hover over the main item. Most of these options can be explored by selections after you just click on the main item.

On the top menu bar, select “Map & Wx Charts” to view any number of charts for different parts of the world, including Canada, Alaska, South America and the Pacific. Or, choose “Airports” on that menu bar to see an airport’s information similar to AirNav.com.

Choose “Flight Planning & Briefing” from the top bar and it opens a default domestic (ICAO is also supported) flight plan form from which the briefing will be built. We’ll brief the second leg of last month’s trip—KFSM, AR to KTBR, GA (See “Route Planning” in July). Enter the route manually. At the bottom left, select Standard, Outlook, or Abbreviated Brief. Use the latter to update a previous briefing or when you need a few specific items. Click the Standard Brief button to generate your route briefing.

To get a broader picture, you can request an area briefing which gives you any briefing level desired for up to ten locations by selecting “Locations Briefing” from the top menu bar as an option under “Flight Planning & Briefing.” This would best be used for planning.

Briefing Elements

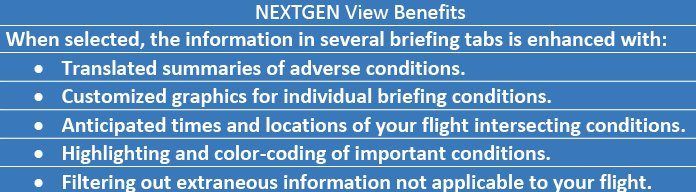

Once you’ve selected your briefing from the flight-plan form, in the upper left corner of the pop-up briefing window, check “NEXTGEN View” if it’s not already checked. NEXTGEN declutters the briefing by eliminating duplicate and unnecessary information. It also adds some valuable features.

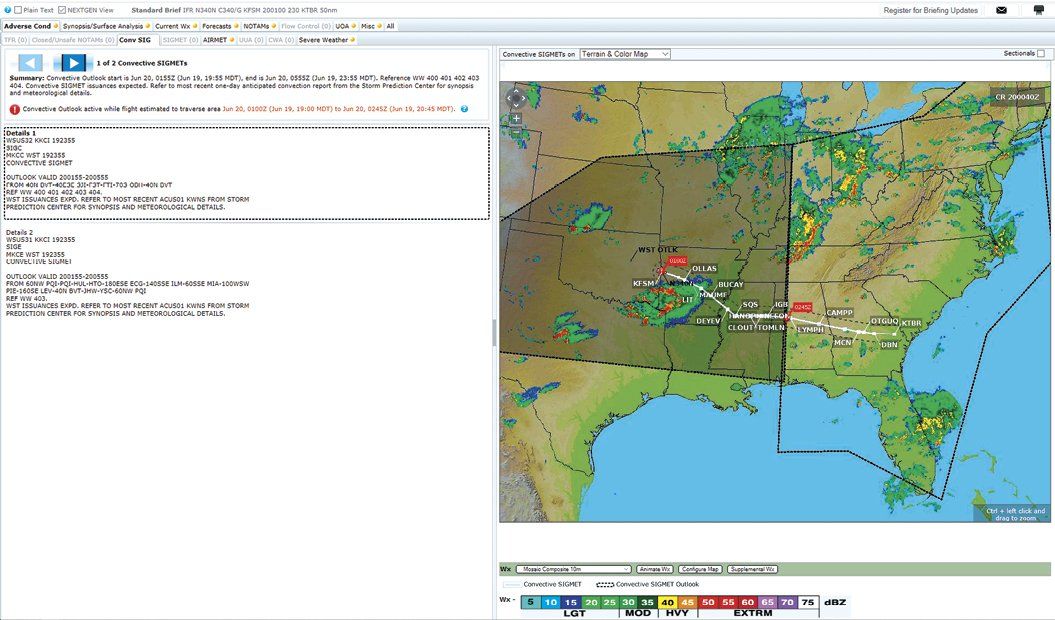

The “Adverse Cond” tab is the main briefing tab. The items on the top menu bar have submenu items as appropriate. Yellow dots highlight unviewed information. Your briefing is complete when all yellow icons have been opened and the yellow dots are cleared.

To understand what each tab offers, click “All” at the far right of the upper tab row. In the upper right corner of the page, you can e-mail or print your briefing and select elements you wish to include, or save your briefing as a pdf on your computer so you can find it at will.

Start with “Adverse Conditions.” It maps your route. Below the map by “Wx” select the weather views you want. Loop the weather by clicking “Animate Wx” after having chosen a view. Click “Configure Map” to select map features you wish to see. Left-click and drag to move the map. The mouse scroll wheel or “+” and “-” buttons at the top zoom in or out. TFRs are automatically shown in text and as blue rectangles on the map including estimated times of entry and exit along your route. This NEXTGEN feature is used in several map displays as for AIRMETs and SIGMETs.

With “Adverse Conditions” still selected, explore the items on the subtab lines. If the AIRMET(s) mention IFR conditions, a third IFR subtab line will be created to address relevant conditions in an AIRMET SIERRA (IFR conditions), AIRMET ZULU (for icing) or AIRMET TANGO (for turbulence).

Select the “TFR” subtab and a Closed/Unsafe NOTAMs yellow dot tells you to check for Adverse Condition NOTAMs at the departure, destination, and alternate airports, specifically closed runways or airports. This could force a diversion to an alternate. The “UUA” subtab shows urgent PIREPS. The “CWA” subtab shows Center Weather Advisories that emphasize weather hazardous to aviation.

The “Synopsis/Surface Analysis” top-bar tab starts with the national Surface Analysis chart. Click on “Supplemental Wx” (lower-right on the chart) to overlay 12-24-36-48-hour Surface Prognosis charts and Radar Summary charts divided into CONUS regions as well as a national CONUS chart. These are pop-up windows, over the briefing window.

The “Current Weather” top-bar tab is based on METARs and PIREPs in the flight plan corridor. Color coding of the stations gives you a quick picture of the route conditions. “Forecasts” from the top bar gives you many options on the second bar. Forecast times are within three hours of the overall flight time. A link (“…click here.”) above the list of charts opens an aviationweather.gov document giving you additional information concerning cloud coverage and graphical area forecast content.

The top-bar “NOTAM” tab shows all current NOTAMs, SUA and FDC NOTAMs. These are presented in a format that’s somewhat easier to navigate than the “sea of words” you’re used to.

Back on the main page top bar, you can use the “Links” tab to access ancillary information including GPS RAIM Data without closing your briefing.

Back on the Briefing window, the main UAS Operating Areas (“UOA”) tab shows these areas in purple. A green dot indicates that the UOA ends before or starts after the flight has reached the area; a red dot indicates that part of the flight will pass through it. Altitude filtering is applied to briefing updates. All UOAs within 10 NM of the departure, destination or alternates are shown; an en-route UOA is only shown where the flight plan altitude is within 2000 feet of the UOA’s altitude range.

The “Misc” tab shows National Hurricane Center bulletins. The “Convective Outlook” subtab maps all issued outlooks in text and map form.

Using AviationWeather.gov

The Graphical Forecasts for Aviation (TAF) chart is at AviationWeather.gov. Select Forecasts, then Area Forecasts. Click GFA TOOL to see the chart.

Under “Forecasts,” select “Aviation Forecast Disc.” (Discussion). It is free text that allows meteorologists to add useful notes that might help you make your go/no-go decision.

End-of-Briefing Summary

Your briefing should answer these questions: Are you expecting IFR, broken navaids, mountain obscuration, or mountain waves, icing or thunderstorms? Where’s the nearest VFR? All this informs your final decision.

Once the “Go” decision is made, return to the Flight Plan browser window. Filing generates a NAVLog. Generally, you cannot amend a flight plan within 46 minutes of your ETD. Your flight plan will be deleted two hours after filed departure time if it’s not activated. You can create a return flight plan as well. Exit the session by logging out in the upper right corner of the Flight Plan page.

On the “Home” page, find the How-to Videos on the lower left. Video 5, Flight Plan Route Briefing, expands on the topics covered in this article. You’ll surely find additional videos of interest.

Surprisingly Helpful

As the author and editor reviewed this material, they were highly impressed with the comprehensive yet easily navigable information this Leidos web site presents. It’s a far cry from the earlier DUATS and Lockheed Martin efforts and is truly an excellent resource.

The only things missing are the MOS/LAMP forecasts that we’ve discussed recently, which are probably missing because they’re not (yet?) recognized by the FAA. Inexplicably, the graphical area forecast is missing, but that’s on AviationWeather.gov. Other than those, this might well turn out to be your go-to briefing resource.

Fred Simonds, CFII has great respect for weather, especially in Florida where thunderstorms can pop up almost any time.