It’s Food Network’s fault. You and your buddies from Jacksonville have a hankering for some Cajun food from New Orleans. Hundred dollar gumbo, here you come.

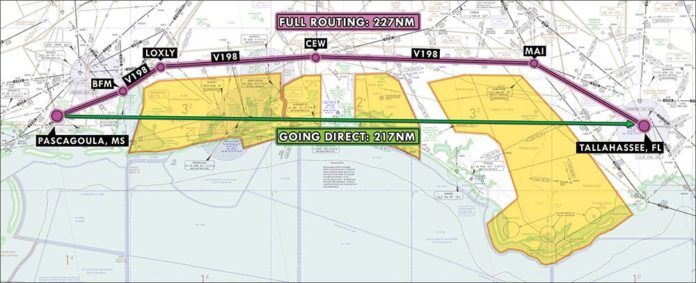

Your Saturday morning flight from Florida’s Atlantic coast to Louisiana traverses two hundred miles of military Special Use Airspace from Tallahassee to Mobile. You file a route inland—KJAX..SZW..MAI..CEW..SJI..KNEW—that takes you north of all that SUA via Victor 198.

Once inside Tyndall Air Force Base’s airspace, though, you get a sweet surprise. The controller asks, “November One Six Charlie, would you like direct KNEW?”

You answer with the approved version of a “Heck yeah!” and sure enough you get direct to New Orleans Lakefront, right through all that SUA.

The weekend was a culinary success and Monday afternoon, with bellies full, you head back to JAX. The route’s a reversed version of your original filed one. An hour or so into the flight, you’re in Mobile Approach’s airspace, thinking about the shortcut you got on the way out. “Mobile Approach, One Six Charlie. Can we get direct JAX?”

“Unable,” the busy controller replies. It worked last time. Why not now? Airspace—like wind and fuel prices—can be fickle. This rapidly changing climate can seriously limit aircraft routing options. Let’s take a look at those limitations and options.

MOA Constrictors

The invisible walls in the sky that mark Special Use Airspace—restricted areas and military operation areas (MOAs)—can go live at any moment, at the military’s discretion with little input from ATC. The military bases adjacent to my facility, for instance, are only required to give us a fifteen minute “heads up” before going active with a mission. That’s just enough time to reroute our existing traffic.

The hours of operation for each of these airspace chunks should factor into your flight planning process. Every sectional chart has a table of the SUAs on that chart, including a “Time of Use” column. Some have times and days of the week, like “0830-1730 MON-FRI”. Others simply state “CONTINUOUS” or “INTERMITTENT”. Either way, that tells you when the SUA may be active.

But an SUA isn’t like the corner grocery store that’s actually open during the hours marked on its front door. Those SUA times only show when the military may use the airspace. The military can pack it with fighters and training flights from opening to closing time, or not launch a single plane, depending on their mission requirements for the day. Of course, when you’re planning a flight during the SUA’s stated Time of Use there’s no way of telling if the SUA will be empty or swarming with afterburning F-16s.

Once you’re en route and getting near it, however, the controllers working in the vicinity of the SUA should be fully aware of its current status. If you ask for direct and the SUA happens to be empty, you might just get cleared right through it. ATC may even offer you the shortcut outright if they see you’ve specifically filed around it.

It’s largely a matter of timing. A case in point: our three local MOAs don’t operate on the weekends or early in the mornings. Our airport’s scheduled air carriers don’t know that and file around them 24/7. All day Saturday and Sunday, or any day before 8am, we’ll chop out a few fixes from their routes and clear them directly through the MOAs.

Finding a Middle Ground

Remember, though, that airspace is three dimensional; a change of altitude may make it possible to also change your route. SUA blocks have upper and lower limits that are marked on the charts. A couple of thousand feet can make the difference between a shortcut and the long way around.

Say the floor of a high altitude MOA is 11,000 feet. If I get a Bonanza filed for 12,000 westbound and she requests a shortcut through the MOA, I can’t approve it. However, I can offer her that shortcut at 10,000 feet. I prefer striking deals than to having to say, “Unable.”

Of course, the altitude change has to make sense. A Gulfstream at FL370 is not going to descend to 10,000 feet to save a few miles.

Border Crossings

SUAs are only one factor in the routing decision chain. There’s also the general traffic flow issue.

Two adjacent air traffic facilities can be likened to a pair of neighboring countries. In an ideal, utopian world where peace prevails, they may open their borders and let anyone cross wherever and whenever they please.

What if the authorities in one of the countries are getting overwhelmed? To maintain control, they may close the border and establish checkpoints for those coming and going. It’s slower-going for the people actually trying to cross the border, but allows the government to monitor the flow and safeguard their own people. Once the trouble is over, they may reopen the borders.

ATC facilities continuously adapt to the complexity of traffic flowing in, out and through their airspace. At low traffic levels, they may use random procedures, leaving the borders wide open for aircraft to cross at any point. But if traffic levels increase, they may institute “gate” procedures. Aircraft need to be routed through specific points—those border checkpoints or gates—so that the receiving facility gets an organized stream of traffic via specific geographic fixes and altitude ranges.

If the traffic continues to pile up, the receiving facility may introduce “flow” procedures. A common flow request is to space the incoming traffic a specific number of miles in trail (MIT). Normally, ATC centers use five miles between aircraft, but with an MIT program the first facility is required to provide increased spacing, up to even 30 miles, for the second facility via those gates. It gives receiving controllers breathing room.

The more intense the traffic flow, the less likely you’ll be getting a shortcut. Radar facilities serving Class B airports, in particular, are extremely structured in their routing. They rely heavily on Standard Terminal Arrivals (STARs) and Standard Instrument Departures (SIDs) to get their traffic in and out of those “gates.”

Points in Space

When you want a shortcut, you should consider how extreme your request might be. There is such a thing as too short.

The FAA’s airspace system is built around twenty Air Route Traffic Control Centers (ARTCCs). Each Center’s HOST computer knows all of the fixes in its own airspace plus those of its adjacent Centers. Beyond that, it only knows a few basic fixes. If your entire route keeps you within the boundaries of one Center or two adjacent Centers, there should be no technological reason you’d be declined.

However, if you’re going across three or more centers’ airspace, it’s ideal to file at least one fix within each center. That way their HOST computers can keep up. Not doing so makes more work for ATC. Controllers may have to manually add fixes in their own airspace to your route so that HOST can both calculate your position properly and hand you off properly to the next facility. That extra effort can be really annoying—and less likely to happen—when things are busy.

So, if you were to fly from Atlanta to Los Angeles, you would fly through Atlanta, Memphis, Dallas, Albuquerque, and Los Angeles Centers. You should therefore have a minimum of five fixes in your route to ensure your flight is processed properly. Don’t forget the fix for your arrival procedure. With the development of HOST’s replacement, ERAM—En Route Automation Modernization—the system may become more robust, intelligent and flexible.

Make Nice

As always, a little courtesy and understanding goes a long way. Controllers are just folks trying to get the job done, and a pilot with a bad attitude won’t be hleping his own cause. I’ve encountered plenty of rude pilots and those are usually the least likely to get what they want. The nicer the pilot, the more I try to help—Human Nature 101.

Don’t nag the controller. Make your request and be patient. Getting any shortcut worth having in the first place will require coordination with other controllers, often in other facilities, and that coordination takes time since each controller may be busy. But before you even make the request, consider what we’ve discussed: Special Use Airspace status, time of day or year, traffic, the complexity of the airspace you’re traversing and the distance. Take all that into account and be realistic.

Not In This Lifetime

There are some areas in the country where shortcuts just don’t happen. I have a friend who flies for Southwest Airlines. “We will ask for direct as much as possible,” he admits. “But we know when to ask and when not to. When flying in the Northeast you would just get laughed at if requesting a more direct route.”

That piece of sky—the bubble around La Guardia, John F. Kennedy and Newark airports—is hopelessly complicated. New York TRACON controllers I know talk (and brag) incessantly about how fouled up it is. The only things keeping it running are the clearly defined inbound and outbound routes. Introducing the wild card of a plane on a strange shortcut through that spider’s web of fixed routes compromises safety, and that simply won’t work.

Overall, there’s no magic solution for getting the shortcut you want. It depends on tact, timing, location, overall traffic complexity, and—sometimes—plain dumb luck. Be patient and work with, not against, ATC. If you’re in the right airspace, at the right time, talking to the right controller, you may just get everything you’re requesting.

Take the long way On Purpose

What if ATC offers you a shortcut and you don’t actually want it?

While I tell my controller trainees to get the aircraft to its destination as quickly as possible, that’s usually tempered with, “You can’t fly the airplane for its pilot.” Despite all of our technology and radars and flight plan systems, we controllers are not clairvoyant or all-seeing. When offering a pilot a shortcut off a perfectly good route, we can’t always be certain of his intentions.

There are many reasons to decline a shortcut. ATC doesn’t know your limitations or desires beyond what’s in your flight plan. What if you’ve filed as a /G, but forgot to update your onboard GPS database and need to use ground-based navaids? What if you’re on a checkride and your flight examiner wants you to fly from VOR to VOR? Perhaps your company requires you fly the route a certain way to save some fuel.

A flight instructor in Miami told me about a recent instrument training flight from Tamiami Airport to Immokalee Airport. He’d filed KTMB..MIAMI1.WINCO..PHK..JIBTO, finishing up with an arcing VOR RWY 18 into KIMM. The JIBTO fix is the VOR approach arc’s initial fix.

On departure, ATC completely ignored his filed route and gave him direct WINCO, direct KIMM. The controller probably thought he was doing them a favor, but the shortcut negated the purpose of the flight: VOR instrument training.

My suggestion to the instructor was to make use of the remarks section of the flight plan by adding something like, “IFR FLIGHT TRAINING: REQ VOR 18.” Approach and tower controllers down the line can see the remarks on a paper flight progress strip, and Center ATC views them electronically. That should tell the controllers that your routing was deliberate. They should at least ask if you want a shortcut before just rerouting you. —TK

What does Tarrance Kramer enjoy more than some fresh NOLA gumbo? Giving pilots shortcuts across his southern US airspace.”