You receive a letter from your family scribe, inviting you to a reunion in Statesboro, GA. It sounds like fun. Even so, Statesboro (KTBR) is a long way from your home in Santa Fe, NM (KSAF).

There’s a Cessna 350 Corvalis in your hangar itching to go anywhere. The 350 is built to travel—170 KTAS, 1300-mile range, Garmin Perspective avionics, and AP, WAAS, ADS-B, the works. The airplane has TKS deicing and a hot prop but is not known-ice (FIKI) qualified. It has supplemental oxygen to reach its service ceiling at 18,000 feet.

Build a Route

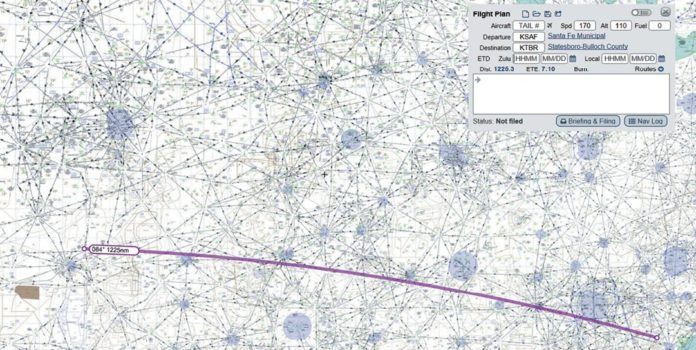

You begin roughing out your trip east. You choose SkyVector because rubber-band route editing is simple and lets you visualize the route. Start with the direct route from KSAF to KTBR. It’s about 1225 NM. Oops; need a fuel stop.

Graphically, you look at that direct route and zoom in to what looks like the halfway point. Next, find a fuel stop with instrument approaches and reasonably-priced fuel. Fort Smith, AR (KFSM), 46 NM short of halfway looks like the right choice. It’s a bit to the north but gets you out of the Hog MOA you’d be going right through.

You now have two legs: KSAF to KFSM, and then KFSM to KTBR. Let’s plan the first leg.

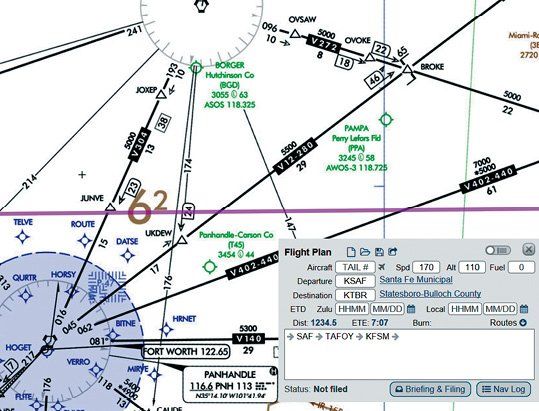

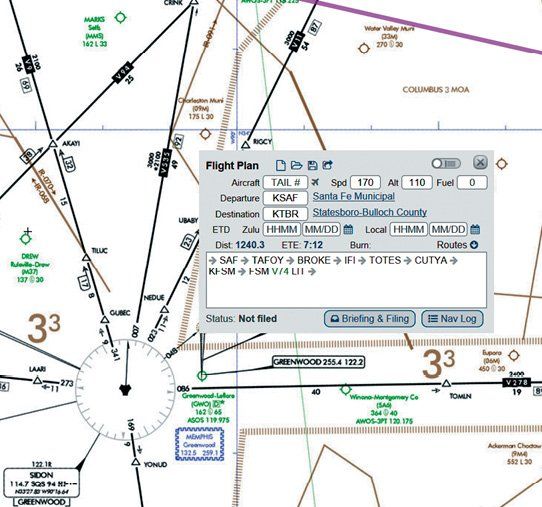

Departing KSAF on the direct route, there’s high terrain right away. You look at the departures and discover that the TAFOY TWO lets you climb to 10,000 feet, the highest MEA along your route. You add TAFOY2.TAFOY to your route.

This is a long flight, so you want to minimize distance and go as direct as possible. You scan the route from TAFOY to KFSM on the chart, and it doesn’t pass through any special use airspace (SUA), so you could go direct. But, you want to comply with the AIM guidance (see below) and pick a fix or two in each center’s airspace. You zoom in on the chart to see TAFOY clearly, then just scroll the chart to the east along your route, looking for fixes on your route that you could add.

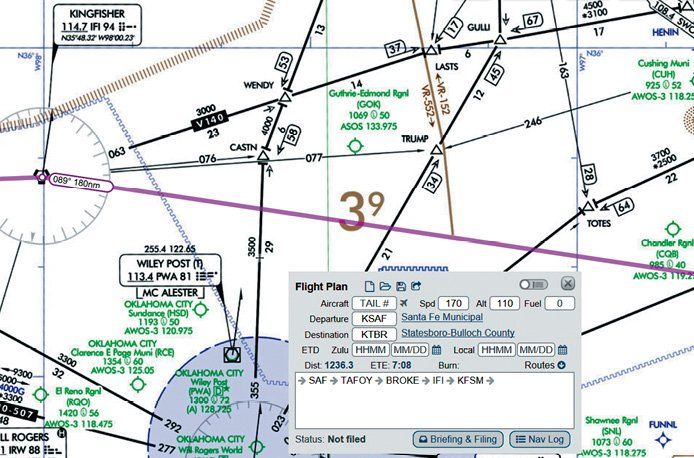

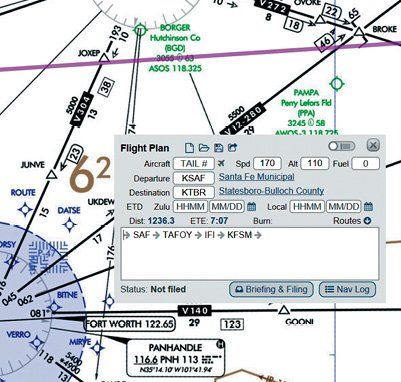

The first is JUNVE, just northeast of the Panhandle VOR and in Albuquerque Center’s airspace a bit before you enter Fort Worth Center. As you scroll east, you notice that your route goes through Oklahoma City’s airspace, which, at 11,000 feet, might be best to avoid. You add the Kingfisher VOR (IFI), northwest of OKC, to get around that airspace. You then go back to JUNVE to see if there’s a fix more in line with IFI. There is. You change JUNVE to BROKE.

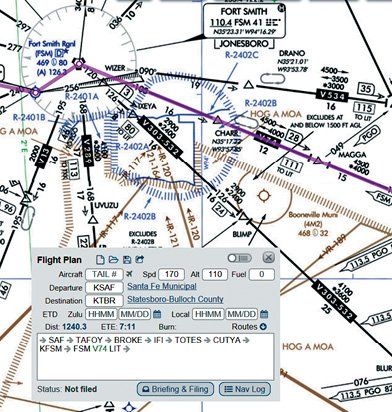

After IFI, you slice through a bit of Kansas City Center and need a fix in that airspace. It’s a few miles north, but you add TOTES. A bit further you re-enter Fort Worth Center airspace and note CUTYA is right under your route, so you add it. KFSM is only 75 miles away, so you’re done with this first leg. You’ve added the departure, avoided OKC, and added several “convenience” fixes, all adding only about 11 miles to your total.

On to KTBR

Departing KFSM, you run into restricted airspace immediately. To stay clear, you go from the airport to the FSM VOR. You file initially for 9000 to remain below the floor of R-2402B and C, then climb to 11,000. Scanning ahead on the direct route from KFSM to KTBR, you note the Columbus MOAs just south of Memphis. You consider adding Holly Springs VOR to your route to avoid the MOAs, but that puts you right through Memphis airspace.

So, you decide to deal with those MOAs first and add the SIDON VOR (SQS) to your route. Now you fill in the blanks back to FSM. You add V74 out of FSM to Little Rock (LIT) as that keeps you out of the HOG MOAs.

East of Sidon V278 runs you through a corridor between the Columbus MOAs to the north and the Meridian MOAs to the south. Exit the corridor on V278 at UYSEF. You nick just a little corner of Alert Area A-440. When active, it extends to 6500 feet MSL, so you will be above it. It’s not illegal but perhaps unwise to fly through it.

You scan ahead along the direct route from UYSEF to your destination and notice that you go through a small slice of the Bulldog MOAs. To avoid that, you add the Dublin VOR (DBN) just 56 miles from KTBR. Then, between DBN back to UYSEF, you look for fixes to add. You see that just after UYSEF you enter Atlanta Center, so you add GOTBY intersection, just south of the Vulcan VOR. That’s 202 direct miles to DBN, but all in Atlanta Center. Nearing KTBR, you enter Jacksonville Center’s airspace, where your fix is your destination. All good. Total distance is now about 1257 miles, about 32 miles or 2.6 percent more than direct while staying out of everyone’s way.

The route was entirely planned on SkyVector, but any chart-based tool—even paper—would work as well with this technique.

MOAs and Airways

Occasionally a Victor airway parallels an MOA. Charts show Victor airways cutting right through the middle of MOAs. Can you really do that? No, there is no airway corridor reserved for civilian aircraft. Yes, you can fly through with ATC permission. Whether you’re on an airway is irrelevant. Plus, the AIM cautions that random impromptu routes should remain three miles from an active MOA.

Restricted airspace regulations are in 91.133 and apply to all aircraft. You can fly through restricted airspace if the controlling agency gives you permission, either directly or via ATC. The only way to know for sure is to ask the controller who owns the sector.

We’ve found that it’s just best to plan to avoid SUAs because there’s no way to predict whether they’ll be active or not, and planning to go through risks a last-minute course adjustment that could add significant distance.

Random Impromptu Routes

A little-known rule applies to pilots seeking to fly GNSS (formerly GPS) direct. Buried in AIM 5-1-8.d.1, the FAA labels such direct flights as random impromptu routes, which can only be approved in a radar environment. ATC will monitor such flights, but navigation is on us. The first leg is such a route. In the second leg, you mix random and structured Victor airways. Random routes are defined by route description waypoints, intersections, and NAVAIDs. Mind that these are not reporting points.

The FAA requires at least one waypoint for each ATC center the route enters. These waypoints must be within 200 NM of the preceding center’s boundary. Measuring this is difficult. Instead, as we did above, define multiple waypoints or intersections that lay on your random routes, figuring that more is better and efficiently meets the rule. These waypoints are aerial breadcrumbs. Any controller can look at the route and see exactly where you are going. If vectored off-route, the controller can conveniently clear you to the next waypoint.

Many flight planning tools offer auto routing or look up previous ATC-cleared routes. We’ve found that the kind of detailed planning we did here gives us a much better understanding of our route and better prepares us to fly it. Simply picking someone else’s route and filing it leaves a lot to discover later.

The Sectional Check

It’s smart to review sectional charts along the route. There are two high mountain ridges over 10,000 feet, just north of your route. If you fly the DP to TAFOY, it takes you south of that and is an orderly way to depart KSAF. The remainder of the route is clear, but it’s good to have the cannulas handy.

Whoa! What’s the black circle around KFSM? It’s one of the few remaining Terminal Radar Service Areas. Dig out your AIM. Operationally, it’s an area within which voluntarily participating pilots can receive additional radar services. The tower is Class D. The remainder of the TRSA usually overlies Class E airspace beginning at 700 or 1200 feet to assist in transitioning from the en-route to the terminal environment and vice versa. It doesn’t affect you.

Your decision to land at Fort Smith was not taken lightly. There are no SIDs or STARs. You check its web page and discover that there are about six airline flights daily.

At KFSM the FBO is attended continuously and offers self-service fuel. A tower, restaurant, rental car, and overnight accommodation are all at hand. There is also top-tier maintenance on the field, but no oxygen service.

Now review the NOTAMs. There are many. None will affect the flight except an FDC NOTAM that raises LNAV MDAs for the RNAV (GPS) 1. A second check is in order shortly before you depart.

Alternates

If the weather is down at Fort Smith, it could be best to land earlier. West of KFSM, several small airports can be alternates including KGZL, KMKO, KVBT, KMLC and F10. KGZL was chosen because it’s nearest KFSM which means it’s the least distance off course. You could also go north to Fayetteville and find any number of airports.

In truth, you select an alternate based on approaches. It gets tricky because one suitable approach at an airport doesn’t mean others are. Many have nonstandard alternate minimums which require scrutiny. For instance, at KASG, the RNAV 18 RNAV cannot be used as an alternate approach at all. Be sure to check for availability of services.

Approaching KTBR, the nearest airport is Savannah, GA. It’s only 35 NM away. But that is mostly a commercial airport with prices to match. You might want to look further.

Many electronic flight bags can automatically suggest alternate airports and optimum cruising altitudes. Whether at 9, 11 or 13,000 feet, the time and fuel burn differences decrease with altitude due to increasing tailwinds. Eastbound, higher is generally faster.

Weight and Balance

The Cessna 350 is touchy about weight and balance. It can easily exceed forward CG if lightly loaded, such as with just the pilot aboard. In this case, all baggage will be stowed as far aft as possible to eliminate the need for ballast.

Since the aircraft has both maximum takeoff and landing weights, compute the weights and CG for both cases. On takeoff, the aircraft weighs 3368 pounds, just under the maximum take-off weight of 3400 pounds and within CG. On landing, if 70 gallons have been used, you’re about in the middle of the envelope.

If you had to land immediately after departure, you should burn off 23 gallons or 138 pounds to get down to maximum landing weight of 3230 pounds.

Summary

Three pilots collaborated on this, and given the number of possible techniques, we were surprised that we all followed essentially the same one. It doesn’t matter whether you use online tools like SkyVector or FltPlan, or EFBs like Foreflight, Garmin Pilot, or WingX, the general process is to look at the full route, then break it into legs if needed, then add waypoints to skirt airspace you want to avoid. This is often an iterative process as you saw here, but the end result will be the shortest route that meets your needs.

Your route is planned. Next month, the wild card—weather.

Fred Simonds, CFII regards airplanes as magic carpets to anywhere. See his web page at www.fredonflying.com.

Re MOA’s and Airways: Since when do you need ATC permission to fly vfr thru an MOA? I do it often, flying from KYKM to KUDD, usually with flight following, no permission asked or answered. I assume your point of reference is strictly ifr (as is the title of your website)

On 9/14/18 I flew from Ada OK (KADH) to Statesboro GA (KTBR) to visit my wife’s family. I filed direct as I almost always do and got direct. The only waypoints I ever put in are an IAF if I am expecting an approach and have a good idea of which one I will be using. On this flight I believe I had a slight deviation for an active MOA but I always ask ATC about them well in advance so I can plan the deviation if needed as far out as possible.

I don’t understand all the “broken field running” between KSAF and KFSM. I have flow in this region for decades and never found it to be the least troublesome. From KSAF D> PNH D> IRW D> KFSM easy peasy. At 11000 you will barely notice either Amarillo or Oklahoma City. There is a brief frequency change which is nothing to get ruffled feathers over. IFR or VFR same-o same-o.

I try to “play nice” and avoid MOAs where it is not too inconvenient. But I also remember the great airspace grab when this formerly pristine airspace was grabbed and made into quasi-controlled airspace. The promise was the government would continue to let us use the airspace as we had been without restriction. That like most government promises has eroded over time. Only once did I have a ZFW controller get excited about an MOA whose floor was 2500 feet above me and I never entered. If this is an IFR flight I would expect the potential for MOA deviations if they were “hot”.

If “as filed” is typical for this region/these ARTCCs, looks like all set.

But this approach to route planning can be less useful (for example, in Northeast) when Clearance/Ground responds “Full route clearance, advise ready to copy.”

The route that was “filed” understood.

What was the actual IFR ‘route clearance’ issued by ATC, and if en-route amended clearances, what was the actual “route flown”.

The issue of filing a fix in every center is one of those archaic “rules” that persists because no one has challenged its legitimacy. The original reason was because center computers lacked the storage capacity to effectively figure out long range direct routes – they did not have the ability to store every fix or airport throughout the country, therefore the computer needed the bread crumbs. I was a Chicago Center controller for 23 years (long retired), and any long range directs the computer didn’t recognize, we simply solicited the lat/longs for the fix/airport for computer entry, which worked fine, although a bit cumbersome.

However, the capacity problem was rectified years ago – center computers have plenty of capacity to recognize all fixes/airports throughout the country. Direct routes through multiple centers are easily handled – I do it all the time. In fact, controllers often issue long range directs on heir own. A fix in every center is an unnecessary burden to flight planning – someone should look into abolishing it.

I do agree with routing around SUA – it’s simple, and if you compare distances, it rarely adds more than a few minutes to a flight.

As a CFII, one thing I recommend is to file a fix within 50 miles of the departure airport before filing direct, especially if the departure airport is a small GA airport or non-towered. Why? If the pilot files KXXX – KYYY, the computer will have no problem with it, but the controller issuing the clearance likely has no idea where the destination is (unless a major airport). Filing a nearby fix gives the controller a hint for what direction you wish to go, so that an appropriate clearance can be issued quickly and accurately.