The comfort level we have while flying in the system comes from the protective layers built within. There’s near-continuous ATC communications and radar coverage. There’s weather assistance when offered or requested, and also traffic advisories. Life can be sweet under IFR.

Among the caveats, though, is the fact that the guaranteed traffic separation works great with IFR aircraft, but not so much with VFR aircraft. On top of that, even those who always fly IFR must be in VFR mode at certain times, e.g. to depart and pick up a clearance, or to cancel IFR at or before the final landing phase. Even if you had those protections all the way in, though, you could be left to your own devices if VFR traffic conflicts occur. And they do.

Into the Mist

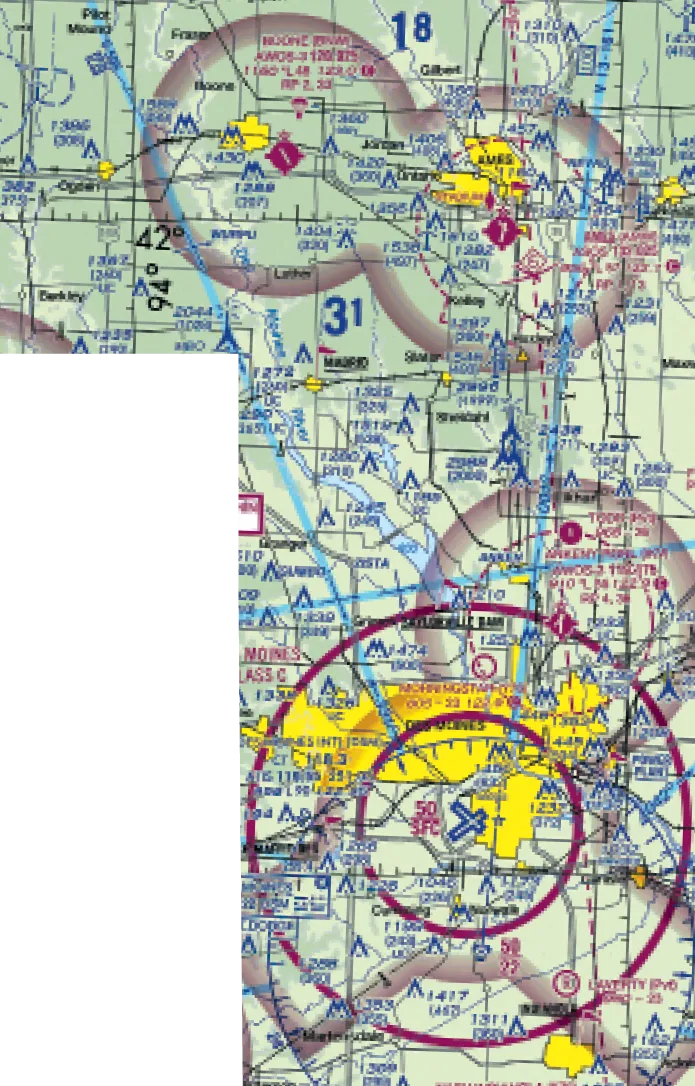

Case in point: You’re departing Hutchinson, Kansas for Boone, Iowa. It’s a two-hour leg in your Mooney, plus an additional 15 minutes to fly an approach into KBNW. The weather’s low—typical for spring—so you’re prepping for a couple of backup destinations should ceilings take a turn for the worse. In fact, Hutchinson’s not all that great, reporting 200 feet and three miles. You’re on the fence, but with multiple precision approach options to 200 feet, you determine it’s just good enough to depart and get back in.

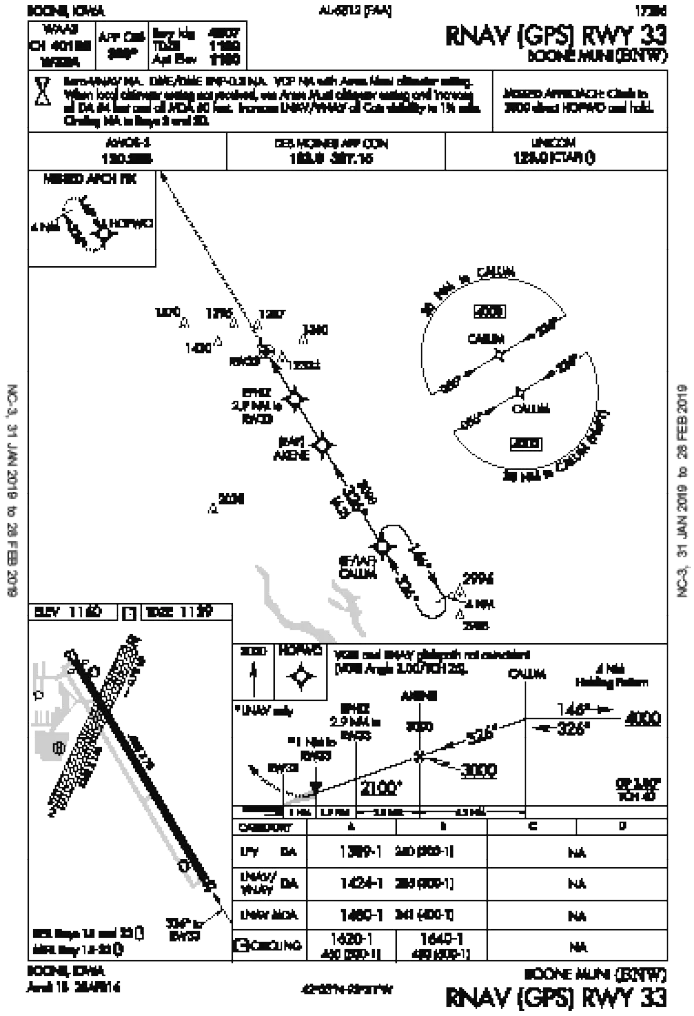

Meanwhile, Boone Muni is 500-5 in mist, and you’ll plan on the RNAV 33 approach. This is an LPV procedure with a DA of 1389 feet, 250 feet above the touchdown zone elevation of 1139. How do you know if the weather will stay put by the time you get there? Well, there’s a TAF at Des Moines 28 miles to the south, calling for 600-foot ceilings over the next several hours. So you don’t expect the weather to get any lower; there’s a decent margin above approach minimums if it does. Carry on.

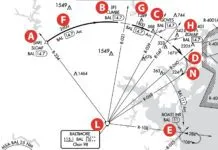

The alternate going on the flight plan is Ames, Iowa, just to the southeast of KBNW. Ames is reporting 600-2. By the regs (91.169), this is just good enough to use as an alternate since Ames has an ILS (and three LPVs); you’re covered for any runway and plan on using 31 based on winds. It’s also near Des Moines, so you use the TAF there just as you did for determining forecast conditions for Boone.

Thirty miles southwest of Boone at 7000 feet, you pick up the AWOS. Good news: Winds are calm and the ceiling has risen to 700 feet. Meanwhile, the visibility has dropped to 4 miles, but you’re still plenty good to make it in. You tell Approach you’ve got the weather and request direct CALUM for the RNAV 33. You get “Cleared as requested,” and five miles from the fix, you get “cleared for RNAV 33 approach.”

You catch a big item requiring clarification with ATC: Are you cleared for the straight-in approach you’re conveniently set up for, or must you fly the hold-in-lieu-of-a-procedure-turn as depicted? You tell approach you’d like to get a clearance for a straight-in approach at CALUM and receive as much: Nobody else is coming or going, so they’d presumed the straight-in. Still, it was a good move on your part to confirm. The final course comes in at CALUM and you descend to 3000 feet. Approach has you switch to the CTAF and you’ve got the option to cancel in the air or on the ground. All standard stuff, and it’ll be a few minutes before you can even consider cancelling. Carry on.

In the Blind

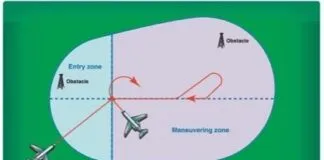

Then another, larger dilemma pops up, one where ATC can do little to help. You hear the controller again: “Before you go, there’s VFR traffic that appears to be in the pattern at Boone.” You reply that you’ll keep watch for traffic and switch to the CTAF on 123.0. Now you’ve got an LPV glideslope coming in at AKENE and announce a 5-1/2-mile final for 33. There’s no reply from the other traffic, which you’re not equipped (yet) to see on either your panel-mounted or portable GPS.

A call in the blind: “Aircraft in the pattern at Boone? Mooney 345 is on a three-mile final for 33.” No response. Three options pop into your head. You could continue the approach until in VMC and look for the traffic, hoping for the best. Not a good idea.

Option 2? Go missed now while you’re well above pattern altitude and over two miles out. You’d climb on runway heading to 3000 feet and, if need be, hold as published at HOPWO. Meanwhile, call Des Moines and let them know … what? That you want a re-clearance to CALUM? A hold ‘til that traffic clears out? Option 3 is to miss, have Approach divert you to Ames, park and have a granola bar while you re-file to Boone. An hour will have gone by and you can safely assume the field is clear. Or can you?

Lesson Learned

It’s below 1000 feet at Boone, so there shouldn’t be VFR traffic there, right? Well, you’ve just blown that theory. Legal VFR minimums apply, which for KBNW (class G below 700 feet AGL) are a mile and clear of clouds, not three miles and 500 feet below clouds until class E kicks in at 700 feet. You have seconds to take action, so it’s Option 2. Just as you’re powering up, there’s a call from a Cessna 172 on “left downwind for 15.” Seriously? Even if you had time to flip through the AIM and argue that traffic on final (you) has the right of way, there’s no way of verifying from inside the clouds that anyone’s aware of you, much less giving way.

You let the Cessna pilot know you’re on a go-around and ask how long ‘til he’s on the ground. “One or two more in the pattern at the most,” he says. You can now keep going with Option 2, climb away, call ATC (you never did cancel), and request clearance back to CALUM for another straight-in. You’ll double-check for traffic with Approach and triple-check on the CTAF and never again assume an airport is free of VFR traffic, even when you’re on approach in IMC.

Elaine Kauh is a CFII in eastern Wisconsin. She’s been on both ends of IFR-VFR traffic conflicts and, contrary to popular belief, does not flip through the AIM while talking on the CTAF.