According to the NTSB, in 2017, 94 percent of all aviation fatalities, 330 lives, were lost in general aviation.

One factor in these accidents is a lack of cognition. Cognition is “the mental process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses.” It includes processes such as knowledge, attention, short- and long-term memory, judgment and evaluation, reasoning and computation, problem-solving and decision making, comprehension and language. We use all these cognitive functions in flying. Is it possible to improve them and so fly more safely?

Your Brain

Most of us understand that we have both short- and long-term memory and they behave differently. Without reinforcement, our short-term memory lasts about 30 seconds and has a capacity of about seven unrelated items that decay quickly. That’s why controllers aren’t allowed to issue more than three instructions at a time.

Short-term memory works well for small tasks like changing a radio frequency or responding to a controller request. You can improve your short-term memory by focusing on the item(s) at hand. Reciting the item aloud definitely helps and is built-in by our readbacks when flying.

Mnemonics can help; feel free to build your own or search for one you like on line (there are hundreds out there).

Your brain processes information and puts it either in short- or long-term memory. Long-term memory capacity is much greater and the decay rate is lower. Some advocate the use-it-or- lose-it theory, but research shows that the information is just harder to reach due to newer overlying long-term memories.

We all forget things, perhaps chronically or just once. One Commercial applicant failed to replace the dipstick during preflight. After takeoff, a film of oil appeared on the windscreen—with his examiner on board. Oops. Bet he never forgets that again.

Decay over time is one reason why the FAA has currency and flight reviews. You are less likely to forget how to manipulate the controls because continuous eye-hand tasks become overlearned and automatic. Taking an IPC, the instructor will (should) help the pilot recall information that’s buried deep enough in long-term memory that it’s not sufficiently accessible.

Interference can occur when new information affects information already there. In flying, many procedures can interfere with each other, especially if they are similar. One student nailed his non-precision approaches. We then undertook the dreaded ILS and subsequently his non-precision approaches suffered.

Memory improvements come with rehearsal or practice and can be enhanced by the use of mental images. Rehearse by repeating the information aloud. Teach others. Many CFIs ruefully admit that they did not really know the material until they had to teach it.

“Chunking” helps you organize information into smaller pieces. If you’re told “wind 270 at 15”, it might be easier to remember “twenty-seven, fifteen.” When you need the information, you recall it and divide it into its components. Using the CRAFT (C learance limit, R oute, A ltitude, F requency, T ransponder) clearance format is a great example of organizing information into usable chunks.

Shorthand can be very useful because it bypasses your memory. Use the FAA Clearance Shorthand by borrowing symbols that make sense to you and create your own shorthand for the rest. Remember that if you develop your own shorthand, you’ll have to decode it later.

Checklists are a mixed blessing. I had a student who took an hour to preflight a 172. He carried a set of Cessna screws and other small hardware to replace anything missing. And he found stuff missed by dozens of earlier preflighters. The checklist focuses on items in the list. This pilot’s all-inclusive approach encompassed the entire airplane.

Some pilots prefer a flow as we’ve discussed in these pages. Check several things, then verify they were done per the checklist. Flow lists help you focus more on the airplane and less on the checklist. Lessen the chance of error by verbally acknowledging each item.

Keep your head in the game. Attention is a blessing because it pulls you back to reality, as when you hear your N-number. It’s a curse while you’re wondering which approach you’ll get. Training and experience help you focus on safety-related thoughts, especially mentally getting and remaining ahead of the airplane.

Avoid the complacency that comes with “Been there. Done that. I know what’s coming.” One example is being given an approach that isn’t the one you’ve flown a lot recently. In 1977 a KLM 747 and TWA 747 collided. The KLM captain expected to hear cleared for takeoff and began his takeoff roll. But the controller said “Taxi into position and hold” because the TWA was still on the runway. His expectation cost 583 lives.

Emotional Stress

In flying, emotions can deeply influence your ability to perform, especially affecting your judgment. Stress is the body’s response to demands placed on it. Something causing stress is termed a stressor.

Student John and I flew the long IFR cross-country required for his ticket. With IFR conditions everywhere, we set off for our destination. I began stressing over fuel due to headwinds. Another stressor was being placed in an indefinite 20-NM hold near the terminal area. The stress ramped up when a commuter aircraft arrived. Having less fuel, we got the approach first.

John started the ILS. Needles centered, all was well. Then he had a panic attack entering the clouds. I learned then that John was petrified of being in cloud, a condition called nephophobia. I took the controls and landed.

There was no time to let stress paralyze us. We redirected that energy into working the problems instead. Indulge your emotions later. The FAA tells us that fear is a normal emotion but must not be allowed to progress to panic.

This situation creates a bucket of emotional stressors, the kind related to intellectual activities, particularly to in-flight problem solving. Even making a simple decision can be a major stressor, such as deciding to fly or not.

Stress peaks when you must perform a complex or unfamiliar task requiring your full attention. The more difficult the task, the greater the likelihood of stress. Yet some people are invigorated by the challenge. The right amount of stress leads to optimal performance, in the middle between boredom and panic.

There are two types of stress—chronic and acute. Chronic stress is the S in IMSAFE, typified by job stress, money, health, or family problems. Acute stress is placed on you by current issues: fuel, headwinds, sick passengers. Chronic stress amplifies acute stress. To understand the effects of stress on your flying, start by examining all the stressors in your life. The Internet offers several Life Events Stress profile checklists, the longer the better. It’s a first step in learning how to manage chronic stress.

Effects of acute stress include tunnel vision or fixation, where you focus on one problem, excluding all others, bringing to mind the CFIT crash of a DC-10 into the Everglades while the crew was focused on a burnt-out light bulb. You could lose your instrument scan, and your decision-making skills erode. Stress inevitably impedes verbal communication, usually when you need good communication the most.

Self-check your stress level in-flight. Green indicates no unusual stress, not overloaded, ahead of the airplane. Yellow denotes an increased stress level and/or a sense of working close to capacity. Red of course means high stress and likely overload. Reduce your stress before yellow goes red. In IFR, our workload can go from green to near-red in an instant. We learn to react quickly when necessary, as with a change of arrival or approach or with a controller’s rapid-fire instructions.

Reduce acute stress by taking a five-minute break and relaxing. Engage the autopilot or let another pilot fly. Slow, deep breathing can also help.

Anticipating yellow or even a red condition, take a mental break beforehand. Preferably while en route, review the approach, airport information and weather. If you’ve been even moderately high, consider adding a bit of oxygen as suggested in last month’s article, “Flying High.” Take a few minutes to relax in the green zone to anticipate possible problems. On arrival you will be prepared and proactive while staying in the green.

We speak of multitasking as a time-saver. It’s not, because one task interferes with all the others. Psychologists speak of the poor judgment chain, where one bad decision increases the probability of another. This chain can start a vicious cycle because each error increases workload to correct the error. As workload and stress increase, the probability of introducing more errors grows. Break that circle by acknowledging the error and immediately correcting it.

Shortcuts are likewise a bad idea. In speaking with the chief pilot for a major airline, he said, “Practically every deviation report I see includes the word ‘rush.’ Rushing and flying are as incompatible as crying and baseball.” Every report he saw included at least one deviation from Standard Operating Procedure, a phenomenon called procedural drift.

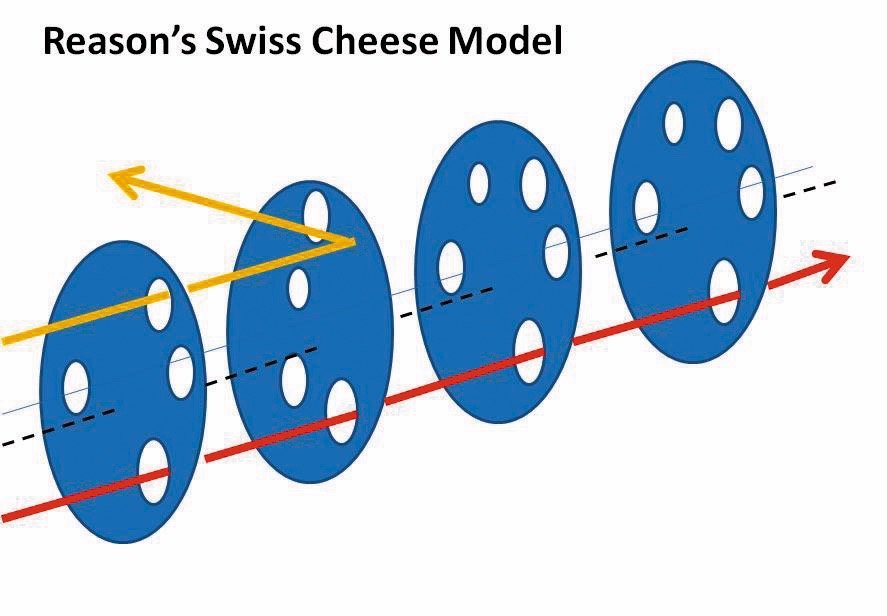

The Swiss Cheese Accident Model

Proposed by scientist James Reason of the University of Manchester, the Swiss Cheese accident model looks at slices of cheese as human defenses against accidents. The solid portion of each slice represents a barrier to an accident. The randomly-laced holes in the cheese represent dispersed weaknesses in separate parts of the system.

As in real life, the weaknesses vary continuously in position and size in all the slices. An accident occurs when holes in all the slices line up, permitting what’s called a “trajectory of accident opportunity” allowing a hazard to pass through all the holes in all the defenses, leading to an accident.

Reason theorized that most accidents can be traced to one or more levels of failure. The first is organizational influence(s) such as “this flight has to go” or skimping on training when money is scarce.

The second is unsafe supervision, as a CFI might inadequately oversee a student, or permitting chronic deviations from standard operating procedure to become normal.

The third is creating, knowingly or not, preconditions that make unsafe acts possible. This might include fatigue or nonstandard communications practices.

Lastly, the unsafe acts themselves are the ultimate level of failure.

Reason distinguished latent from active failures. A latent failure spans the first three slices and includes subtle contributory factors that may lie inactive for a long time until they contribute to an accident. An active failure might be an engine failure or navigational error.

The model has found wide application in aviation including airlines and healthcare. And now it’s come to GA! —FS

Judgment

Pilot judgment is the mental process we use to make decisions. Over half the pilot-caused GA accidents are due to bad judgment. You might falsely conclude that some pilots have inherently poor judgment. Yet as early as 1991, psychologists have known that judgment is a learnable skill, far beyond the old chestnut that good judgment comes from experience and experience comes from bad judgment.

Perceptual judgment is based on visual perceptions, such as knowing when you’re too high on final. Important as they are, they do not require much thought and are easy to learn and apply consistently.

Cognitive judgment, the second type, is more complex. Information is more uncertain. The pilot has more time to think, especially since there are usually more than two alternatives. The respective risks are harder to weigh. The final decision is distorted by non-flight factors including fatigue, stress, pressure to complete the flight, and more.

Judgment is learned primarily from experience, especially from the experience of others. Good decision-making is best learned through a systematic program rather than trial-and-error, contrary to that old expression. The FAA’s integration of risk management into the Aviation Certification Standards was a sound but very late step. Judgment is learned by experiencing as many decisions as possible, most safely, scenarios in a classroom, simulator, or on a computer.

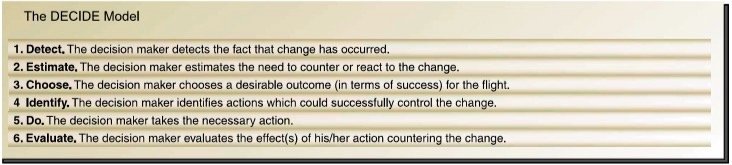

The two-part judgment model first calls for headwork, and then attitude. Headwork requires finding and determining the relevance of all information related to the flight, diagnosing them rapidly and evaluating alternative actions considering the risk of each. For this part, we apply the well-known DECIDE model.

Get the most out of DECIDE by memorizing the meaning of each term. Any time a change occurs from ideal flight, go through all six steps. Consider each with care, do what each suggests. Then do it again.

Think of yourself as a detector of all changes in-flight. When one occurs, judgment evolves into action if needed by following each step. Repeated use will morph DECIDE from cognitive to perceptual, which is our goal.

The second and oft-neglected part of judgment is attitude, where irrational reasons influence the decisions we make—the classic example being get-there-itis making problems seem less severe. Attitudes toward risk-taking develop from training and experience. You could be a cautious Kilroy or an inveterate risk-taker.

There is no logical reason why pilots allow external forces to influence sound decisions, but they do because we are human. Good judgment says that we should not allow these forces to distort our rational thinking.

The five antidotes to hazardous attitudes are designed to prevent such aberrations. Most of us realize which of those attitudes really pertain to us. One of the best ways to apply the table is to avoid situations that make you vulnerable. Good pilots exercise good judgment by recognizing signs of trouble early and taking corrective action before a critical situation arises. For example, plan a fuel stop halfway to your destination if it’s close to your maximum range in terms of time. You’ll be spared the temptation to convince yourself that there’s enough fuel to make it without stopping.

Good judgment can be elusive. Under pressure, it can be difficult to maintain perspective. Bad judgment that works out makes it difficult to develop good judgment. If bad decisions don’t come out bad, we tend to repeat them.

In 1986, Space Shuttle Challenger broke apart 73 seconds after liftoff from Cape Kennedy. The 24 previous shuttle launches were successful even though they had known leaks in the O-ring seals between rocket stages. NASA knew this was wrong. Yet there seemed to be no adverse consequences, so the flights continued—until Challenger.

We must understand that outcome does not determine whether a decision is good or bad. A decision is good or bad regardless of the outcome. For a crude yet powerful example of this, consider Russian Roulette. Just because your first turn had a good (lucky) outcome doesn’t mean the decision to play at all was sound. Good judgment requires discipline, but it increases safety. Just think of all the accidents we could avoid simply by clear-headed thinking.

|

AERONAUTICAL DECISION MAKING — HAZARDOUS ATTITUDES |

|

|

ATTITUDE |

ANTIDOTE |

|

ANTIAUTHORITY: DON’T TELL ME. |

FOLLOW THE RULES; THEY’RE USUALLY CORRECT. |

|

IMPULSIVITY: DO SOMETHING QUICKLY. |

NOT SO FAST. THINK FIRST. |

|

INVULNERABILITY: IT WON’T HAPPEN TO ME. |

IT COULD HAPPEN TO ME. |

|

MACHISMO: I CAN DO IT. |

TAKING CHANCES IS FOOLISH. |

|

RESIGNATION: WHAT’S THE USE? |

I CAN MAKE A DIFFERENCE. |

Fred Simonds, CFII tries to let his head rule his heart in all aspects of flying.