As students of aviation, we are familiar with our regulations, the AIM, Advisory Circulars and other instructional, regulatory and best practice FAA guidance publications. But questions remain about what’s legal. One sure, but unpleasant way to answer them is to attract the FAA’s enforcement apparatus. This begins with your friendly neighborhood Aviation Safety Inspector, and can lead to suspension or revocation orders, “plea bargaining,” trials and appeals with the NTSB, and ultimately, the federal courts. There is a better way.

The FAA Chief Counsel Office has been issuing letters of interpretation in response to inquiries for decades. Once only available from legal research and aviation compliance companies, the FAA now publishes them. At www.faa.gov, search for “Legal Interpretations & Chief Counsel Opinions.” They cover a wide variety of subjects including logging flight time, whether manufacturer Service Bulletins are mandatory, airline and charter pilot duty time limitations, and the multiple and often-grey areas where Part 91 and Part 135 charter operations collide.

Recent IFR articles on circling approaches and alternate airport planning referred to some of them. Today, we will look at a few more, some old, some new, some applicable specifically to IFR operations; others more general, some sensible, and others that are a bit silly.

Equipment Requirements

In interpretations to Daniel Murphy in 2011 and to Thomas Letts in 2017, the Chief Counsel said an aircraft with a red beacon and flashing wingtip strobes has a single anti-collision light “system” under 91.209(b). All three components are required and must be working and operating, subject to the section’s exception for safety of flight. It’s a bit unclear if the FAA’s legal group is referring to a pilot who chooses to, say, add a red rotating beacon to the strobes-only system in his Cherokee or Cirrus, or to an installation marketed and packaged as a single system. I heard but have not confirmed the FAA is currently reviewing this.

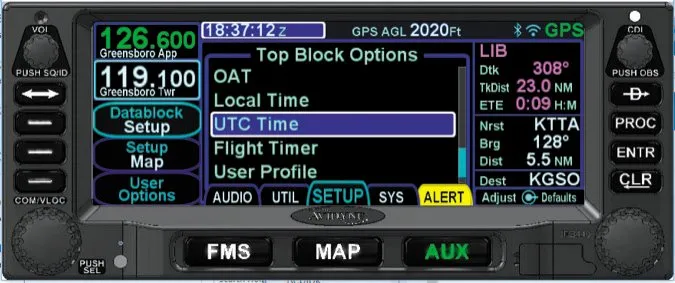

“A clock displaying hours, minutes, and seconds with a sweep-second pointer or digital presentation” is required by 91.205(d)(6). In 2016, the Chief Counsel told us in a letter to Ebiri Nkgumba the clock “must be an installed appliance… with a permanent clock presentation.” Our fancy aviation watches and tablet-app timers don’t qualify.

Timekeeping does not have to be the appliance’s sole function, so your King ADF with the timer button or your EFIS will comply.

The “permanent” presentation requirement raises an interesting question. Modern navigators have timers and clocks that can display on a main screen. Set that way, it probably complies, but if you have to switch back and forth among screens, it probably does not, although that nuance has not been addressed.

Approaches, Departures, Holds

Although published takeoff minimums do not apply to Part 91 operations (91.175(f) and the 1991 Landis letter), the 91.175(d)(2) prohibition against descending below MDA without the required minimum flight visibility does, according to a 2012 interpretation to Gary Thomey.

Are procedure turns optional? This was answered in 1993 with a letter to Tom Young of the Airline Pilots Association. Procedure turns on approaches (holds-in-lieu and teardrops) are mandatory unless one of the conditions in 91.175(j) applies—vectors to final, cleared straight-in from a fix, on a NoPT route, or a timed approach from a holding fix.

On the other hand, standard published time- or distance-based holding leg lengths are maximums according to a 2011 letter to Bill Young. A pilot may shorten the legs. There’s an exception, however. If ATC specifies the length, it becomes an instruction, which 91.123 requires be obeyed absent an emergency. (Shortening a published hold might be one of those legal-but-unsafe things. If you shorten a hold, just tell ATC.)

IFR in Uncontrolled Airspace

Some IFR requirements apply generally; others only to controlled airspace. A flight plan and clearance are required by 91.173, but only in controlled airspace. The reg doesn’t require either when operating IFR in uncontrolled airspace. But, as the Chief Counsel reminded Daniel Lamb (and the rest of us) in 2016, a technically legal operation can be careless and reckless under 91.13, depending on the circumstances. The warning is not hollow. In a 1993 case, George Murphy was tired of waiting for his IFR release from a nontowered airport, so he took off uncontrolled IFR into low ceilings with passengers, figuring he would reach VMC before entering controlled airspace at 700 AGL. The violation for operating without a clearance was dismissed, but that did not stop the NTSB from giving him a 90-day flight vacation for careless and reckless operation.

Lost Communications

The clearance limit in the typical IFR flight is the destination. If communications are lost and we do not encounter visual conditions, 91.185 requires us to fly to the destination and then to an IAF, where we are to hold until our ETA before flying the approach. Written in the days of vacuum tubes and limited radar coverage, it hardly seems applicable today. Many argue it is best to fly directly to an IAF and get down and out of the system as soon as possible.

That may be the exercise of good judgment under the circumstances (which the AIM recommends in 6-4-1), but former IFR editor Jeff Van West’s effort to get official blessing for the procedure went nowhere. The Chief Counsel’s January 2018 response reaffirmed a series of prior interpretations that 91.185 means exactly what it says.

Training and Currency

A 2011 letter to Rolf Scholz is merely the latest in a long series of Chief Counsel interpretations stating a CFII is the only “authorized instructor” for logging and endorsing instrument tasks other than the three hours of student pilot training “on the control and maneuvering of an airplane solely by reference to instruments” in 91.109. The Scholz letter deals with instrument tasks for a WINGS program IPC, but there are similar interpretations for simulators and other training devices, the instrument training for the commercial certificate, and even for training beyond the minimum 15 hours dual required for the rating.

Unlike 90-day passenger currency which is both category and class specific, instrument currency under 61.57(c) is only category specific, according to an interpretation to Ken Williams of the Venture County Sheriff’s Department in 2012. For example, if you are instrument current in a single-engine airplane, you are instrument current in a multi, but not in a helicopter.

A CFI may count approaches performed by a trainee in actual instrument conditions (not under the hood) for her own currency (2008 Letter to Ron Levy), but only the pilot doing the flying in an aircraft or operation requiring a two-pilot crew may do so (1999 to Bill Carpenter).

If you join Joshua Wynne in wondering whether a newly-rated instrument pilot comes out of the checkride instrument current, even without doing six approaches, tracking and holds or an IPC in the previous six calendar months, yes, he does, according to the legal group’s 2008 answer.

A number of folks were surprised when the Chief Counsel said neither an instructor nor a trainee needs to be current for landing with passengers on an instructional flight, even with a student pilot. Three related interpretations informed us that during a training flight neither a CFI nor a trainee is a “passenger” within the meaning of 61.57(a) and (b). Landing currency is therefore not required, according to the letters to Kris Kortokrax in 2006 (night currency) and John Olshock in 2007 (student pilots). These were reaffirmed in a 2014 letter to Roger Schaffner (day currency).

Don’t Ask; Don’t Tell

Before running to your desktop, laptop, tablet, or Remington to ask the Chief Counsel your favorite question, be aware that in some cases, the answer has made no sense from either a regulatory or policy standpoint or brought common practices into question. The opinions discussed in the recent article on choosing alternates effectively saying you may not list a Class D airport with “Alternate NA” on the approach charts as an IFR alternate but may list the dirt strip next to it (assuming the same severe clear conditions at both) is an example, but there are many, many more. They can be difficult to identify in advance, but one common thread is that it’s something most people have been doing for years, believing it was proper and encountering no problems—until someone ruined it by asking for “clarification.”