More than once I’ve been accused of needing to get a life. I’m not sure what they’re talking about, but in my spare time I do enjoy reviewing various aviation publications, including accident reports and incident summaries.

Periodically, the Aviation Safety Reporting System publishes the most pertinent pilot reports in several areas. As I was reading through these, I potentially saw myself in more than one. Thus, I thought you might wish to review them with me to see if there’s anything we can learn.

The narratives below were culled from the top fifty on icing in or near IMC. We’ll review carburetor icing, structural icing and ground icing.

Carb Icing in an RV-4

The IFR Van’s RV-4 was clearing heavy weather when the engine started running rough. The pilot applied carburetor heat, but the engine lost 4 to 5 inches of manifold pressure. He advised Approach of the engine problem, and requested and received a descent to 7000 feet.

During the descent, full power slowly returned. The pilot leveled at 7000 in VMC. All engine items were normal. The pilot advised ATC and continued. Despite visible moisture, there was no ice on the wings or windshield. However, the pilot believed that he had experienced carburetor ice.

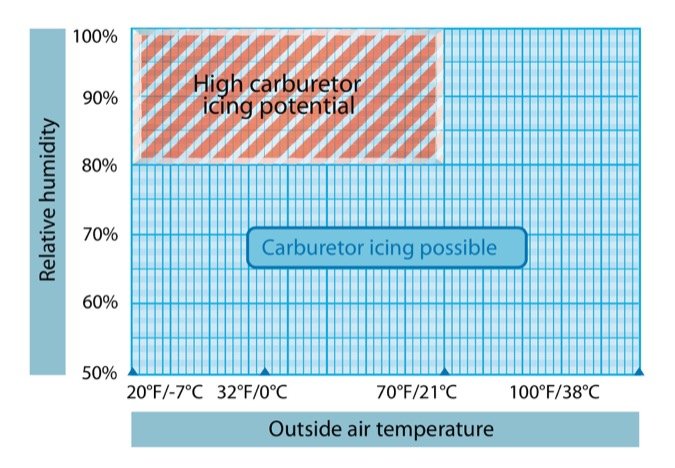

This is entirely possible because fuel vaporization and the accompanying decrease of pressure in the carburetor venturi causes a temperature drop of up to 60-70 degrees Fahrenheit. The visible moisture was above freezing, hence no ice. But the carburetor venturi was much colder.

The pilot was surprised that the carburetor ice took so long to clear. In his situation it would have felt like eternity. In the future he will consider using carb heat sooner and more aggressively when IMC at or near freezing.

The chart reveals that icing can occur even in outside air temperatures as high as 100 F (38 C) and humidity as low as 50 percent. Hot, humid days over warm water are also a setup for icing.

Carb Ice in IMC

An IFR pilot launched into an area of forecast freezing and precipitation in his initial flight path. He climbed normally to 9000 feet andthenexperienced carburetor ice in temperatures of 35 degrees F with occasional moderate-to-heavy rain. RPM dropped about 400 RPM, but he maintained altitude. Also, the throttle froze. A descent to 7000 resolved the problems.

This very-repentant pilot wrote that he was influenced by “get-there-itis” and operated in unsafe conditions, even knowing better. His words: “I put myself in a dangerous position and ATC in the awkward position of trying to help out a ‘poor fool’—this is the part I am most ashamed of. ‘Never again’ are the operative words in this case.”

Carburetor ice is subtle but deadly. Though best avoided, apply full carburetor heat at the very first indication of roughness or low RPM and leave it on until after all ice is cleared. Consult your POH for details.

Be PIC

An IFR pilot requested and received 10,000 feet to top the clouds. The OAT was minus 7 degrees. Vectored into a cloud, ice began accumulating on the 182’s struts and windshield. With pitot heat on, his airspeed immediately decreased 15 knots, likely due to structural ice. Wisely, he disconnected the autopilot and requested 12,000. No response from Oakland Center. He initiated a 300 fpm climb anyway. A minute later ATC instructed him to turn immediately to 360 and he complied.

Still IMC, the pilot repeated his request for 12,000 to exit IMC. Instead, ATC issued a turn to an airliner, but the crew saw him on TCAS and had already deviated. His G1000 indicated that they passed about two miles apart at the same altitude. He exited IMC at about 11,500 feet. The ice came off about 40 minutes later during descent. Center informed him to call regarding his clearance deviation.

The Center supervisor heard him out and informed the pilot that the controller was on a landline when he called about his icing issue and climb request. The supervisor understood his need to deviate for icing.

The pilot further said that if the altitude deviation did not resolve the icing issue, then he would declare an emergency and continue. Only 45-60 seconds elapsed between his deviation and the vector from ATC.

Be pilot-in-command. Do what you must do. This pilot used his legal authority and ATC knew it.

Caught on Top

A pilot transiting the Sierra Nevada Mountain Range westbound at 12,500 feet under VFR encountered unexpected clouds and climbed to 14,500. But the clouds were rising and he could no longer maintain VFR. He got an IFR clearance from Oakland Center, entered IMC and began picking up ice. Unable to maintain altitude, he requested lower. ATC began vectoring him to keep him above terrain until he could see Lake Tahoe Airport where he diverted. Again VMC, the pilot canceled IFR. On short final, the pilot advised Center that “things were OK” and landed.

Even so, after landing he was given the controller’s phone number. But fear not! The controller was checking to assure he was all right. The pilot thanked the controller, chalked it up as a learning experience and went his way.

ASRS reports almost always end with self-criticism. Not this time. This pilot turned on the carburetor and pitot heat before entering IMC. He was grateful that he filed a clearance before entering IMC and had a plan in place before things turned ugly.

In his words, “Once IMC and icing began I almost immediately had trouble maintaining altitude, my mind operationally went to: (1) stay calm, (2) fly the airplane, (3) listen to instruction (as best possible), (4) respond to questions asked, and (5) continue to report challenges to ATC. Good training allowed me to later thank ATC for their help and debrief the incident proactively. Later my passenger remarked on the calmness and professionalism he observed.” Way to go!

Icing in IMC

The Grumman Tiger was IFR at 9000 feet and experiencing moderate mountain wave with altitude deviations of 300 feet. An aircraft ahead on the same course reported ice at 8500 as the cloud base with icing above. The Grumman descended below the MEA, entered VMC and reported the OAT as +5 C. At 8500, he could see city lights below and behind.

Without warning he encountered large downdrafts and supercooled rain began to rapidly freeze on the airframe. Pitot heat was applied immediately but was overwhelmed and airspeed indication was lost. Control was maintained, but course and altitude varied widely.

The nightmare disappeared just as suddenly in a few seconds. The pilot twice called for a turn back to the airport. His request was relayed to ATC via another aircraft, through which ATC responded with vectors to the airport. The radio loss could have been due to antenna icing. The pilot thanked the controller, canceled IFR and landed. The ice melted away. The FBO gave the pilot an ATC phone number to call, apparently a check to make sure the pilot was all right. The flight resumed VFR without event.

The experienced pilot had never witnessed the sudden change from no weather and over 10-mile visibility into intense freezing rain. The pilot was falsely reassured by the aircraft ahead of him, believing there was no cause for concern. He nicked himself for turning the pitot heat off too soon once initially entering VMC, because losing the airspeed indicator caused “losing focus at a very bad time.” In fairness, he would have needed a crystal ball to anticipate the nasty weather ahead … yet none are certified.

Stuck in Ice

The IFR Cherokee was descending for an instrument approach. Leveling at 3600 feet, the aircraft started accumulating ice. The pilot requested and received 3000. At that point the pilot began losing radio contact with ATC. Again, another aircraft relayed communications. The pilot informed ATC that he would abort the approach and go to another intersection, then changed his mind back to the original approach. ATC informed him that he would have to return to 3600 feet which the pilot declined due to the ice. Clearly, he was stuck.

ATC finally asked if the pilot was declaring an emergency or if the pilot could do the approach on his own. The pilot elected the latter, and ATC said to stay with him for advisories. The pilot mistakenly thought this canceled his IFR flight plan. The pilot was asked again whether he was declaring an emergency or if he sought to cancel his IFR flight plan. The pilot canceled.

In hindsight, with seven miles’ visibility, the pilot felt he should have canceled IFR when he first saw the ground. He could have flown the approach on his own or perhaps taken the visual.

It Only Works When It’s On

An IFR Cirrus SR-22 was in-and-out of light rime at 9000 feet. The cloud was growing. ATC offered 13,000 as the aircraft ahead was in VMC at that altitude.

While pondering the climb, the pilot noted significant ice accumulating on the windshield and wings. Suddenly the airspeed began fluctuating and dropped to 60 knots. Recognizing pitot-static failure, the pilot disconnected the autopilot and hand-flew using the attitude indicator and standby instruments. He then noticed that although the ice protection switch was on, the pitot heat was off. He turned it on, selected alternate static air and advised Center, who cleared him down to 8000 feet.

He few for two minutes with only the attitude indicator working, before the airspeed and altimeter returned to normal. He broke into VMC at 8000 and the controller further cleared him down to 6000.

Sometimes we fall victim to being creatures of habit. Oddly, he cycled the ice protection switches several times and never noticed the directly adjacent pitot heat switch. This was because most of his personal flying was VFR. He vowed to always turn the pitot heat on before takeoff, regardless of the flight conditions. (This is standard practice for some operators.)

No Way to Stay Legal

The pilot was on top, VFR at 9500 feet. He had no flight plan and was not receiving flight following. He planned to go to an area without ice, obtain an IFR clearance and land at an airport southwest of Minneapolis-St Paul International.

The plan came off the rails when he encountered icing on the windshield and leading edges inside a stratus layer. He tried calling Minneapolis Center on two frequencies, got no reply as ice continued building. His Stratus/Foreflight system reported 200 AGL overcast at Huron Regional Airport in Huron, SD (KHON).

Since turning around might expose him to more ice, he decided to descend through IMC into VMC, emerging near KHON below 2400 feet (MSL/AGL not specified). KHON’s field elevation is 1288 feet MSL. He proceeded to Brookings Regional Airport in Brookings, SD (KBKX) clear of cloud in Class G airspace, landing safely with the wing leading edges carrying 1/8 to 1/4 inch of ice.

This pilot was a prime candidate for a posthumous Darwin Award. He could have collided with another IMC aircraft, struck the ground or an obstacle. He was the perfect poster child for whatnotto do. He could have but did not try the emergency frequency, 121.5.

Icing on the Ground

The student and instructor were returning to KBTL airport in Battle Creek, MI in a Cirrus (type unspecified). A thorough preflight briefing occurred, including runway braking MU values in the mid 20’s (40 and higher is normal) due to thin dry snow over ice. The low MU value was considered an acceptable risk, not ideal but not impossible. The crew briefed the landing and what could happen. The student would fly and the instructor would “shadow” him on the controls.

The approach, flare and touchdown were all normal. On the ground, the Cirrus veered left of centerline and the instructor took the controls. Despite full-right rudder and right-wheel braking, the Cirrus departed Runway 23R into the snow at very low speed. No injuries or damage.

In another case, a Cessna 310’s left engine failed. The pilot secured it and diverted to his alternate. Aligning with the longest runway, ATC reported braking action as poor. After landing, he applied brakes but the airplane began sliding on ice. The right brake locked when it encountered a dry patch of runway. The tire flat-spotted and went flat.

And, at KRNO in Reno, NV, a chartered twin hit a patch of black ice on a taxiway and did a slow, uncommanded 360-degree pirouette, but never left the pavement. After the 360, further braking action was good. The passengers were amused, unafraid and they departed without delay. The reporter stated, “Actually the only thing I can say is be careful out there, especially in the mountain airports, in the wintertime. Make that all airports in the winter time.”

Fred Simonds, CFII prefers his ice in a glass. See his web site at www.fredonflying.com