For years I’ve promoted the notion of a “lazy pilot”—one who’s too lazy to do it wrong and then waste time making it right. “Lazy pilots” do the right thing the right way the first time.

But to be truly “lazy” requires being efficient. Here are some tips to run your cockpit more efficiently.

Preflight

Start your preflight as you approach the airplane. Does it look ready to fly? Are the tires inflated or soft? As a student pilot, I preflighted a new Cessna 152. I discovered at the end that the nosewheel was flat. I’m still embarrassed.

Is anything leaking? Has it been properly secured by the last flier? Was the door properly closed; gust locks installed? Does it look cared for or unloved?

After opening the airplane, put the key on the glareshield or hang it from a knob on the panel so you’re not awkwardly digging for it in your pocket after you’re belted in. Just don’t put it in the mag switch lest you risk a hot mag.

Check the fuel quantity early. If you need fuel, order it while you preflight the rest of the aircraft to save time. Wait until fueling is complete to drain the sumps. Speaking of petroleum, bring an extra quart of oil, especially on longer trips.

Unless it’s cold out and you want to warm your hands, save effort by checking the pitot heat from the cockpit. Just turn the switch on and observe that the ammeter registers negative current flow. If it does, the circuit must be working. You can do the same for a single landing light unless it is a low-current LED light. Same story for the anticollision beacon if there is one. Observing current flow will not work for nav or strobe lights because one of the multiple bulbs could be out and you wouldn’t know.

While the master is on, check the GPS for database currency. The trip could be a no-go or need modification if the database is expired.

Notice a pattern here? We’re being efficient with our motions and potentially saving effort by checking no-go items early. If this makes me lazy, I’ll wear the label proudly. Let’s lazily continue the flight.

After Start

After start, check both comms. It’s a good idea to RAIM check your GPS even if you have WAAS. Similarly, it’s wise to do VOR checks although technically not necessary if you’re using WAAS GPS and don’t plan to use the VOR. A non-WAAS GPS is regarded as supplementary navigation, making the VOR system the primary nav even if you don’t plan to use it. It’s best to just do that VOR check.

Lean the engine as much as possible during taxi and runup. This helps prevent lead fouling of spark plugs. Clearing a set of fouled plugs is annoying and time-consuming. No matter how much you lean you can’t damage the engine at low power.

Before departure, preset everything you can on the panel. Departure is a busy time and you lighten your workload if the panel is preset.

Consider leaving the VOR receivers set in ID mode so you can hear the code. No need to turn ID mode off unless you are listening to voice such as a HIWAS report or communicating with FSS through a VOR. It’s a small time-saver when you have lots to do.

Once when we were number one for an IFR departure ATC gave us a long routing, and pressed us to launch so a bizjet behind us could depart. To save time, we loaded the first couple waypoints and off we went. Once en route, we loaded the remaining route. Just don’t forget.

En Route

It can be a long time between radio calls with ATC. It’s a good idea to check in occasionally to make sure you’re in contact. Avoid asking for a “com check,” which makes you sound insecure. Instead, request the altimeter setting. You’ll confirm what you need to know and get a fresh altimeter setting to boot.

When you tune anything (OBS, frequencies, headings, etc.), turn in the shortest direction. It takes less time, is less wear and tear on the knob and can save going the wrong way if you’re heading coupled on your autopilot.

In the G1000, a blank field always starts at K. The shortest way to A and 9 to 3 is to turn left. The shortest way to Z and 0-1 is to turn right. Learn to turn knobs in the shortest direction.

There is also a feature in the G1000 I call “little knob left.” When you bring up a page with choices, turning the inner knob left offers you choices and saves knob twisting. For instance, when choosing an approach, put the cursor on the airport line. Then turn the inner knob left. You get a Flight Plan inset. Select an airport in this column if it’s available. Otherwise turn the little knob right to find nearest and recent airports in turn. Highlight the one you want and hit enter.

Lazy Arcs

The Instrument Flying Handbook promotes flying a specific heading on a DME arc. This is unnecessary. Heading is not the issue; the arc radius is. Just keep the DME distance where it belongs. Fly whatever heading makes that work.

Preparing for Approach

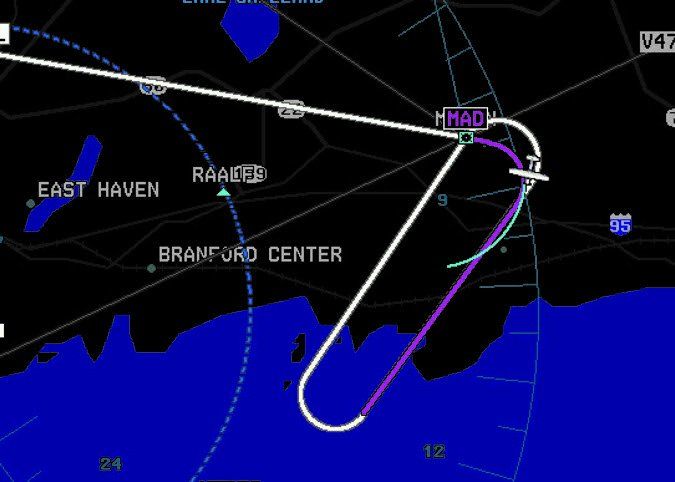

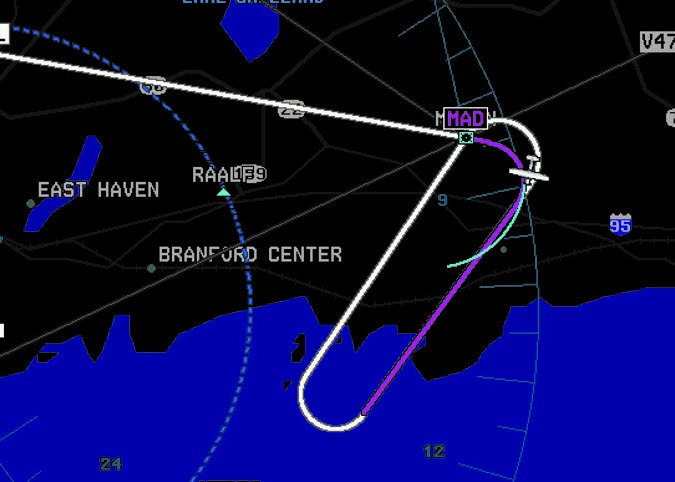

You are approaching KHVN in New Haven, CT. You plan for the RNAV 2, but with two IAFs, one IF, three intersections or the vector, you don’t know which transition you’ll be given. Load the approach but don’t enter the transition. Just leave the screen up. Once ATC gives you your transition, enter it, activate the approach and off you go. Or just plan and request the transition closest to your route.

Lazy pilots get the airplane to do the work. Savvy pilots, especially IFR pilots, make trim work to their advantage. Since a power change requires retrimming, trim after power is set. Avoid becoming truly lazy and failing to trim. A well-trimmed airplane is easier to fly.

At some point, ATC clears you direct to XYZ VOR. If it’s not in your flight plan, set the VOR frequency, center the needle (or turn to the bearing pointer), and you’re on track. Then you can modify your flight plan. Or, just request an initial vector. ATC expects quick compliance, and sometimes fiddling with the GPS takes too long.

Lazy pilots always fly toward something—a fix, waypoint, localizer, etc. Given a vector to a localizer, tuning it in promptly gives you something to fly toward. This helps avoid flying through the localizer and correcting. That’s not being lazy enough. Lazy pilots do it right the first time.

To the extent you can, get into the controller’s head. What seems to be the plan for you? More direct routing? A deviation for weather? Approach clearance or a vector? Be ready. Listen to the destination weather from far away, or check it on your XM or ADS-B so you can plan the right approach to the right runway with the right transition.

Another way to keep your head in the game is to constantly play “What if?” Maintain a high level of situational awareness. Sitting and driving is not conducive to safe IFR. Most of us have experienced the rapid ups-and-downs of IFR workload. You want to be in the zone, not zoned out, when you need to respond in a hurry.

Nothing says you must use the highest level of automation all the time. The slower things are, like en route, the higher the level of automation can be used. When ATC is barking out commands nonstop, or with rapidly converging traffic, turn off the autopilot and fly by hand for less drama.

WRIMTM Elements | Things to Do |

Weather | Get the weather first. Until you know the weather, especially the winds, you can’t know which approach is best. |

Radios | Set all the radios, starting top-down in the stack, in an organized, methodical way. Set everything, including the GPS. |

Instruments | Airspeed—Note approach speeds. Use pitot heat as needed. Attitude Indicator—Working correctly; adjusted for your view Altimeter—Set VSI—Working correctly Heading Indicator—Check with compass Suction Gauge—in the green Turn Coordinator/Indicator—Needle and ball working; no flag |

Minimums | Note minimums for type of guidance, category, straight in vs. circling, any notes |

Time | If the approach is timed, reset your clock and make sure it’s ready to go at the FAF. |

Missed Approach | Know the first two steps—a climb (to where/when) and a turn. Don’t try to memorize it all. |

WRIMTM

Lazy pilots like nothing more than an efficient, thorough checklist to gets things done systematically. Setting up for an approach cries for a methodology like WRIMTM. (See the table.) Following a standard methodology assures that everything is done, and avoids inefficient, possibly incomplete, haphazard, and decidedly un-lazy actions.

Let the Airplane Do the Work

Compute your airplane’s power settings in various phases of flight: climb, cruise, descent, approach and landing. Knowing these, you can set power precisely to get the performance you want rather than guessing all the time.

Another way to make the airplane do the work is to find the right wind correction angle and fly it. In the G1000 (and most EFIS), a track vector line shows where you will be on your present trajectory in the future. Most pilots set “future” to one or two minutes. Fly whatever heading you need to keep the track vector on your course, skipping the time-consuming bracketing to find your wind-corrected heading. Using the track vector like this also improves the accuracy of your turns and approaches.

When banking, use the attitude indicator to start. Ten percent of the true airspeed plus five to seven knots will give you the approximate bank angle for a standard rate turn up to about 150 KTAS.

These tips are intended to make your flying and your IFR life easier. The more precise and organized you are, the less work is required. Should things get fast and furious, you’ll be on your game, ready to do whatever it takes.

Fred Simonds is a working CFII in Florida. See his web page at Fred On Flying.