It’s taken for granted that when you fly a light aircraft, you take care of everything from preflight planning to all the in-flight tasks and securing the aircraft afterwards. All decisions are usually left to one person.

This is such a common routine for many that the risks of what’s known as Single-Pilot Resource Management are often overlooked, especially due to the external pressures that are often present for any flight. In this accident report, the combination of a sole pilot’s pressure to get home and poor weather conditions had tragic results.

Take Off and Crash

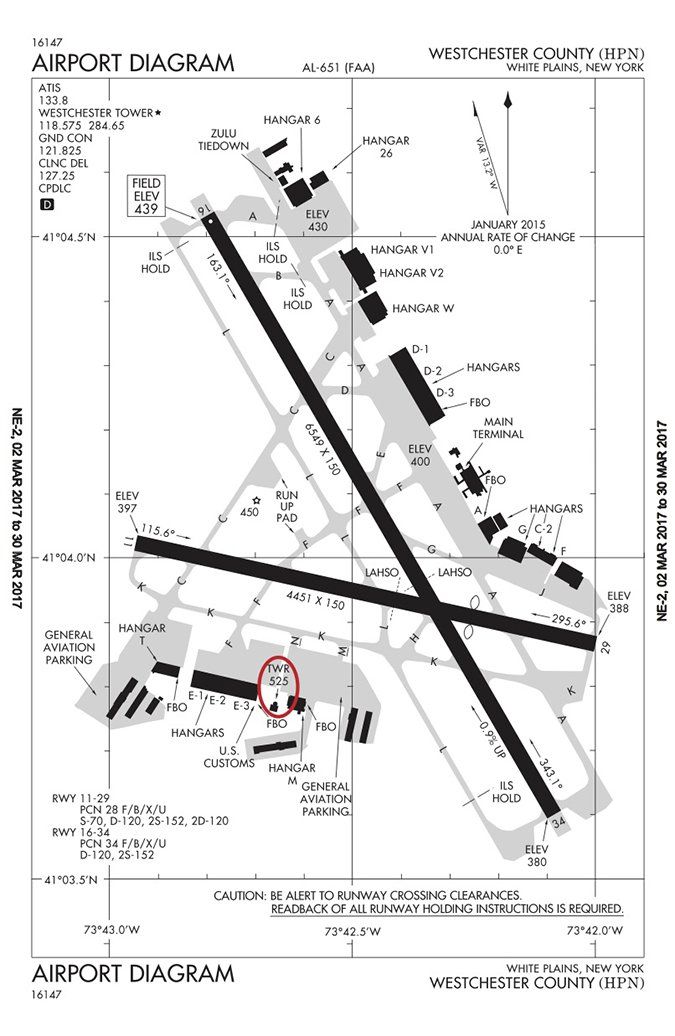

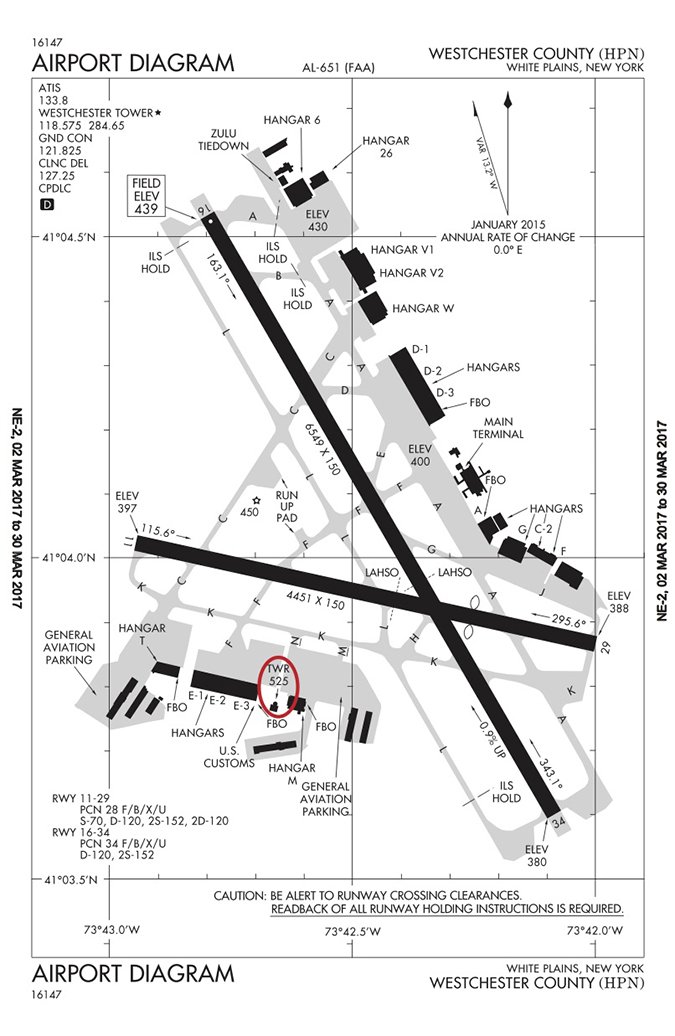

The morning of June 13, 2014, a PA-46-500TP Piper Meridian crashed into trees after takeoff from Westchester County Airport (KHPN) in New York. The solo pilot was bound for his home in Portland, Maine. He had arrived at KHPN the day before to attend a family event.

The NTSB’s report says that on the morning of the accident flight, the private pilot arrived at the airport earlier than the FBO anticipated, but personnel had the aircraft pulled out, topped off and ready to go. At some point, the pilot filed a flight plan for Portland on DUATS, but there was no evidence of a weather briefing from that system or from Lockheed-Martin Flight Service. Moreover, he did not file an alternate airport.

The pilot received a takeoff clearance from the KHPN tower at 8:08 a.m. Investigators found the only radar data for the Piper showed five targets—three on the 6500-foot runway, and two indicating the aircraft in a “shallow right turn” at low altitude. The last return showed the aircraft about a half mile from the crash site in a residential area.

The 65-year-old pilot was estimated to have about 5371 hours total time, with 7.3 logged that year. The last line in the pilot’s logbook was dated Feb. 28, 2014. There also was an endorsement for an instrument proficiency check and flight review, both given on the same day a few weeks before the accident.

Foggy, Rainy Route

Weather conditions would be considered low for an IFR departure, but perfectly legal for a personal flight under 14 CFR Part 91. At 8:15 a.m., the ceiling in the area was reported at 200 feet with 1/4-mile visibility, fog, and a light east wind. After the Piper took off, controllers from Ground and Departure called the tower to ask if the aircraft had departed, and the tower controller said, “I have no idea. We have zero visibility.”

Departing in weather below approach minimums is not uncommon for some Part 91 pilots, but analysis should be considered as part of the planning process and the overall go/no-go decision. KHPN has an ILS for Runway 16. Even if this pilot had been comfortable with zero-zero departures, it seems unlikely that in the rush to leave that morning, he took the time to consider contingencies should a problem arise, or perhaps he didn’t even consider delaying his departure until the visibility improved.

Portland’s weather at the estimated time of arrival wasn’t much better. The ceiling was overcast at 300 feet, with 1.5 miles visibility, light rain and fog. The weather at Portland required filing an alternate under 91.169.

Not relating to this accident in particular, but thinking about any pilot’s failure to file an alternate airport when required leaves but three possible reasons: Ignorance (He didn’t’ know of the well-worn 1-2-3 requirement.); arrogance (He knew an alternate was required, but chose not to file one.); or carelessness (He simply didn’t think it through to realize he needed an alternate.). We’ll suggest carelessness is probably the most benign of these reasons. But if carelessness is the reason, one is left to question the thoroughness of the rest of that pilot’s planning.

Cause

The NTSB reported that disorientation was the final factor that resulted in the crash. The board’s report pointed to vestibular disorientation, in which the lack of visual references causes a person’s inner ear to lack the proper inputs to correctly sense movement and orientation. Radar data indicate a right turn between 600 and 700 feet. The departure procedure for Runway 16 requires climbing on runway heading to 800 feet, followed by a climbing right turn to 320 degrees and 3000 feet.

Did weather cause this accident? One is tempted to categorize this as a weather accident. However, while weather was certainly a factor, it didn’t cause the accident. Instead, it was the pilot’s failure to handle legal (if not fully prudent) conditions that should be within the capability of most instrument-rated pilots.

A probable cause found by the NTSB pointed to the “pilot’s failure to maintain a positive climb rate after takeoff due to spatial disorientation (somatogravic illusion). Contributing to the accident was the pilot’s self-induced pressure to depart and his decision to depart in low-ceiling and low-visibility conditions.”

External Pressures

The investigators’ interviews with those who knew the pilot well included his personal assistant, who said he had a “very important” meeting in Maine. The pilot was known to be “unusually punctual,” and “would have been focused on arriving on time.”

This points directly to the NTSB’s remarks on “external pressures,” quoting an FAA Advisory Circular (60-22) regarding “get-there-itis,” which “impairs judgment by causing a fixation on the original goal or destination combined with a total disregard for any alternative course of action.”

The pilot was a physician and member of a prominent family. He was obviously a busy man, one who was accustomed to keeping a schedule. For any pilot, this opens up the risk factors of external pressures, magnified by single-pilot operations and challenging weather.

Even the best training and most thorough proficiency checks cannot eliminate human factors such as the pressure to get somewhere and the physical effects of vestibular disorientation. But these risks can be discussed, studied and mitigated for any given flight. Those who fly single pilot should have even more reason to be aware of such risks, which remain common factors in IFR-related accidents.

It Happens to All of Us

In a fairy-tale world, we’d all have as much time as we needed to prepare for a flight, thoroughly reviewing the weather, performance, our own limitations, etc. I don’t live in that fairy-tale world. Instead, I constantly try to fit too much into an already-too-short day. The challenge, then, becomes finding at least a middle ground where I can manage the risks of a flight within the reality of a fast-paced life.

I live about a 30-minute drive from our airport. When I’m feeling frantic, anxious or pressured to get going, I use that drive time to calm myself. I’ll mentally review just the critical high-points: IMSAFE, aircraft status, and departure weather. That’s it. No, that’s not enough, but it’s a start. You see, when I get myself thinking about the flight, it kind of snowballs—it continues on its own from there. So, all it takes is a deliberate quick review of a couple critical elements, before I’m thinking like a pilot instead of a pressured, short-on-time crazy person who’s about to go flying.

Years back, I wrote an article suggesting that you could be perfectly safe launching without a thorough weather review. The idea was to briefly look in advance for big hazards and, once underway, watch for them while looking deeper for other risks. Clearly, that kind of abbreviated process is not ideal, but it works for many of us.

So, next time you’re in a rush, recognize it (critical first step) and try to force yourself to think through a few basics. That’ll probably get you to consider more aspects of the flight and can push aside that rushed feeling in place of one that’s aware of the risks of the flight and how you’ll mitigate them. Then, once underway, you can concentrate on the flight itself. It works for me.

Elaine Kauh is a CFII in eastern Wisconsin. She spends most of her instructing time with clients who fly single-pilot IFR and she emphasizes recurrent training and proficiency checks.