The old saying tells us you can’t be cleared for takeoff until the gross weight of the paperwork exceeds that of the aircraft. That hasn’t changed much since Flight Service received reports on Teletypes necessitating cryptic abbreviations to conserve precious bandwidth on 75-baud lines.

Calling Flight Service used to be required to file a flight plan and get a weather review from a specialist with information unavailable anywhere else. Technology has changed all that.

Apps and websites now make the same raw data used by FSS available to all. Now pilots can skip the call to Flight Service and effectively self-brief. Doing so requires knowing what’s needed and how to assess weather using a risk-based approach. Now, the FAA has begun emphasizing self-briefing resources, suggesting that’s where they’re headed.

Requirements

Preflight Action, 91.103(a), compels the PIC to be familiar with weather reports and forecasts for flights under IFR or not in the vicinity of the airport. Implicit in the reg is a method of tracking the reports and forecasts that are used.

What do you need? For Part 91, the FAA doesn’t say. The local TV debutante reading current and future conditions from a teleprompter is enough. Commercial operators don’t enjoy the same freedom. Regulations require Part 121 and 135 operators to use National Weather Service or equivalent products.

The regs don’t say how to comply with 91.103(a), but the FAA has a clear preference—use a standard weather briefing. A standard briefing includes area forecasts, convective SIGMETS, center weather advisories, AIRMETs, SIGMETs, METARs, PIREPs, TAFs, Winds Aloft and NOTAMs. Charts used are the Weather Depiction, Surface Analysis, Forecast Winds Aloft, Freezing Level Graphic, G-AIRMET Graphic, 12- and 24-Hour Low Level Significant Weather Prognosis, 12-, 24-, 36-, and 48-Hour Surface Prognosis, High Level Significant Weather Prognosis, Current Icing Product (CIP), Forecast Icing Product (FIP), Graphical Turbulence Guidance (GTG), National/Regional Radar Mosaics, Radar Echo Tops, Radar VAD Wind Profiles, Visible/IR Satellite Imagery, and Constant Pressure Charts. Oh, my; did I miss any?

A standard FSS briefing organizes information as prescribed by FAA Order 7110.10: adverse conditions, VFR flight not recommended, synopsis, current conditions, en route forecast, destination forecast, winds aloft, NOTAMs, prohibited areas, ATC delays, PIREPS, and additional information.

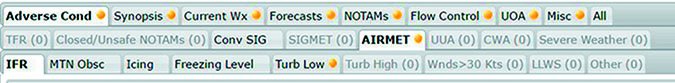

Websites and apps that allow filing of flight plans often provide and record route briefings. Briefings match the Standard, Outlook and Abbreviated formats described in Aviation Weather Services. Common features include organizing weather products into meaningful tabs. Most services allow downloading or printing an entire briefing.

Common tablet apps and 1800WxBrief utilize similar conventions. A dot indicates tabs not viewed. Sub-tabs with information stand out, those without information are grayed out.

Although technology is improving how weather data is presented, it’s still a lot to digest. Experienced fliers take a targeted approach to analyzing weather.

Cut Clutter

Dropping in on a normal day of business at the pointy end of an airliner, the pilots likely only checked three pieces of weather—METARs, TAFs and Turbulence Index—to see if an alternate is required and to check the ride.

How can they get away with this abbreviated approach? They rely on weather situational awareness, a risk-based approach, and availability of tactical information en route.

Spending all that time flying multiples legs a day develops a weather situational awareness. Two factors influence weather awareness—a macro awareness of fronts and geographic effects. A front causing scuzzy weather on a trip to ORD will probably mess up a DCA flight a couple of days later. Geographically, the red radar returns in the Southeast might not be a big deal because of moisture being pumped in from the gulf, but yellow returns over the desert Southwest need to be avoided due to the lower moisture content over the desert.

The volume of information in a standard briefing can camouflage critical data. Hazards should be identified and weather checked to see if additional steps need to be taken to mitigate risk.

The first step in this approach is identifying hazards and sources of risk. Flying a multi-engine jet into big airports with a lot of infrastructure reduces risk significantly. For the rest of us, AOPA offers a Flight Risk Evaluator that is a good starting point.

Weather hazards impact three areas of flight—departure, destination/alternate and en route. Departure and destination/alternate threats include ceiling, visibility, winds, and runway conditions. Can I get back in if something goes wrong on departure? Can I make an approach at the destination/alternate? Can I handle the winds? How’s the landing surface?

AOPA’s Risk Evaluator covers icing, significant amounts of visible moisture, and convective activity. A glaring omission is turbulence. Significant turbulence can cause many problems, especially in IMC or at night.

Access to tactical weather augments initial briefings while en route. Keeping track of destination and alternate METARs is a great way to monitor weather fluctuations. PIREPs are the best way to know what conditions are really occurring. The value of a report is proportional to its age. Having access to weather reports inflight allows decisions to be made earlier, reducing the chance of a weather surprise.

Going to Savannah

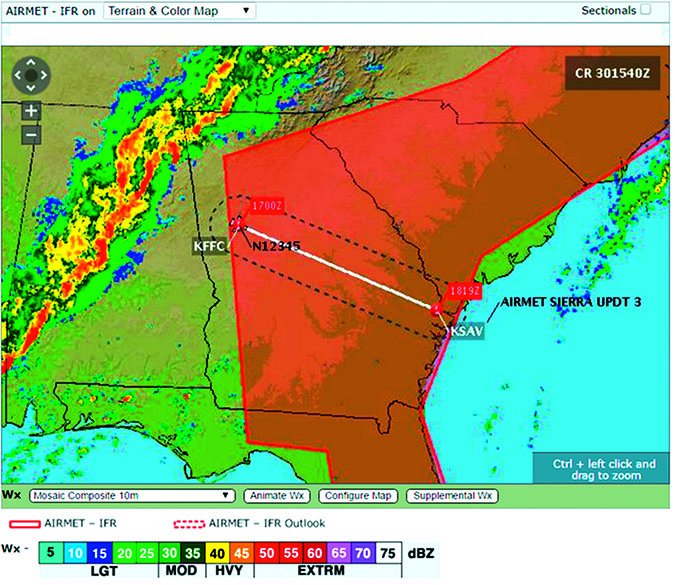

Let’s put these concepts into practice self-briefing a flight from Atlanta Falcon (KFFC) to Savannah (KSAV) in a Cessna 172 using 1800WxBrief.com.

A cold front swept through the southeast yesterday sparking numerous twisters and wringing moisture from the atmosphere. The reward is a beautiful VFR day. The local TV weather person forecasts a couple of nice days and the radar is clear. This covers general weather situational awareness.

We need to investigate potential hazards. KFFC has one runway (13-31), so winds should be checked. En route conditions should be clear, but watch for turbulence. Multiple runways in Savannah lessen the wind risk, but proximity to water and rain-saturated ground means watching temp/dew-point spreads.

Plug the flight into 1800WxBrief.com and select the standard brief to open the briefing in a new window. Start on the left opening tabs (previous page) and associated sub-tabs.

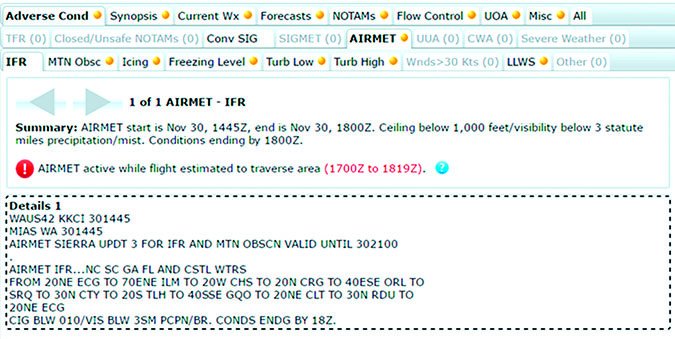

The first tab is Adverse Conditions, with Conv SIG and AIRMET in bold identifying content. The Convective SIGMET indicates a possible issuance for the ETA of 1700Z, the affected area just touching the destination. AIRMETs for freezing levels and turbulence exist. Without clouds or an AIRMET for icing, freezing levels don’t matter much.

But, turbulence is an identified risk. The AIRMET forecasts moderate turbulence below 16,000 feet. To investigate, jump to the Current WX tab to see if any PIREPs confirm the forecast. None are near the route. Next, go to the Forecast and Winds Aloft. Shearing air currents cause turbulence. Search for big changes in wind direction and speed. The winds aloft increase rapidly with altitude, accelerating from 19 knots at 3000 feet to 61 knots at 11,000 feet. This subsides in later forecasts to a 24-knot difference, suggesting that the turbulence will ease as the front moves further off shore.

Continuing with the standard brief, the next tab is Synopsis. Nothing exciting here because it matches the general weather situational awareness we got.

Click on Current Wx to check the departure and destination. At KFFC the METAR reports light winds and a two-degree temp/dew-point spread. This spread is after the coolest part of the day and will certainly widen. Winds, another identified threat, are light. The green dots on the map, indicating VFR, and the “VFR” notation next to the METAR text makes it easy to scan through en route METARs. No reason to dwell.

Since Savannah’s METAR isn’t reporting, looking at nearby KSVN and KLHW METARs shows light winds and high ceilings. The ceilings might mean logging a little actual IMC, but by then we should be below the clouds on descent. The missing METAR is a cue to check it again before leaving and carefully review the TAF; let’s do that now.

Check the Area Forecast. North/central Georgia weather is forecasted clear. The prediction for North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia coastal waters indicates a broken ceiling and gusty winds clearing over the day.

KFFC doesn’t have a TAF, but nearby KFTY and KATL both forecast gusty winds from the northwest at departure, lining up with the runway. Savannah forecasts light winds and a high ceiling breaking up to a scattered layer at ETA.

When we checked turbulence, the winds aloft showed a nice tailwind.

NOTAMs are the next briefing item. The devil is in the details. Note that Savannah’s ILS 10 is out of service, but the forecast winds suggest a visual approach in the opposite direction. The VASI for 28 is out, something to be noted. No self-serve 100LL (ouch) and there are a couple of taxiway closures.

En route NOTAMs abound. Do I care that a 170-foot tower has a light out of service? The advantage of being an instrument pilot is not having to scud-run. The Gen FDC NOTAMs also cause drowsiness and encourage click fests.

Flow isn’t an issue for most of us, although 91.103 requires a pilot to be familiar with “any known traffic delays of which the pilot in command has been advised by ATC.”

The last tab with any interest is Misc, which includes the convective outlook. Since we’ve already determined t-storms aren’t a threat, little more is needed.

Overall, the only threat during this flight is en route turbulence. It is mitigated by flying during the day in VMC with a clear horizon reducing the chances of disorientation. The turbulence was caused by wind shear from strong winds aloft behind the front. Different altitudes might provide better rides. MEAs are well below the aircraft capability, offering many potential altitudes to explore.

We register for briefing updates that send an email when a selected product is updated. For the flight to KSAV, select SIGMETs, Urgent Pilot Reports, and AIRMETs for low-level turbulence.

Although most days are VMC, when it’s time to actually go somewhere, the weather inevitably turns to mush. A day before the example, the southeast was covered in rain following passage of a warm front with a cold front sweeping in from behind that brought severe thunderstorms and tornados mere miles from KFFC. See above.

The process of self-briefing that day would be similar, but with a lot more threats to analyze. Any flight would have to get out ahead of the afternoon squall line or wait until the next day. Embedded thunderstorms, icing and turbulence must be checked. Departure, destination and alternates must be reviewed for winds, ceilings and visibilities, then compared to approach minimums.

Tactical weather information becomes more useful during adverse weather where conditions can change rapidly and forecast accuracy degrades. I’d use the NEXRAD radar looking for any yellow or red ahead. Squall lines can propagate storms well ahead of the line. Embedded t-storms start popping up, making it time to get on the ground.

Phoning a Friend

Sometimes it’s prudent to reach for help. Some airlines require new captains to call dispatch before flight until a minimum experience level. Airlines also encourage calls to dispatch when flying overseas, for good reason. Being new to an aircraft or area means not having the experience to make a good risk assessment.

There are also times when the weather is so dynamic that a discussion with an expert could provide insights. The modern problem is too much information. A weather expert can organize the information into a cogent narrative.

The FAA recommends always getting a standard briefing from a specialist. To the agency, self-briefing serves as a pre-brief. This oversimplified approach works for new, rusty, or inexperienced pilots. But, many times a pilot can accomplish an effective self-briefing using services designed to improve understanding and correlation of weather and NOTAMs.

A list of identified hazards is key to good self-briefs. It focuses attention on determining how much risk a hazard presents for a given flight and tees-up mitigation steps. If the weather conditions are very complex, you’re flying to a new place, or operating new equipment, the self-brief should serve as a pre-brief. The self-brief may identify areas to check en route or another time before jumping into the cockpit. Or, it could indicate a great day to fly with light winds and a stable atmosphere.

Technological advances in availability and delivery of weather information make self-briefings easy and useful. A flight service station specialist still plays an important role when weather is dynamic or unusual. But, most of the time we can leave them chatting around the water cooler about the latest Skew-T diagram.

VFR Flight Not Recommended

Student pilots learn to disregard Flight Service recommendations early in training. This intentional non-compliance breeds from observation and experience. Seemingly every standard briefing includes the admonishment, “VFR flight not recommended.” The student informs the instructor and they decided to go fly anyway.

Guidance in Order 7110.10 advises a specialist to issue a VFR not recommended warning when “sky conditions or visibilities are present or forecast, surface or aloft, that in your judgment would make flight under visual flight rules doubtful.”

“Judgment” is defined as the ability to judge, make a decision, or form an opinion objectively, authoritatively, and wisely. A Flight Service Specialist is objective and an authority when it comes to weather, but their experience is inconsistent when it comes to flying. Marginal conditions for someone on a first solo cross-country could be great for an old bush pilot.

Some specialists are pilots and can discern the significance of weather objectively based on a caller’s level of experience; others can’t. Issuing a VFR not recommended warning may also be viewed by a specialist as limiting liability if something did happen.

Whatever the reason, the VFR not recommended proclamation is overly broad and discourages deeper analysis of the weather. Maybe there’s a reason that section of a standard briefing is missing from websites and apps. —JM

Jordan Miller, ATP, CFII, sometimes calls FSS so much his wife is worried he’s cheating.