The instructor’s voice boomed in the radar room. “What the heck are you doing?” The trainee controller reflexively hunched down in his seat. The instructor leaned in and stabbed at a pair of converging targets on the radar ‘scope at 5000 feet. “Do you see these two?”

The trainee’s voice wavered as he spoke. “N352AM, turn left heading…” The instructor immediately mashed his radio trigger, overriding his charge. “N352AM, disregard last. Remain on course.” He swung his attention back towards his trainee. “Dude, N2AM needs to descend to land. Forget the turn. Descend him to resolve the conflict.”

The trainee nodded and took a breath. “N352AM, descend and maintain 2000. Expedite through 4000 for traffic.” The veteran controller at his side smiled. “See? Instead of vectoring these guys all over the sky, you just resolved the whole thing with one transmission. Work smarter, not harder, and you’ll be fine. Good job expediting him. Keep working.” The trainee nodded, and looked for the next aircraft requiring attention.

Scenes like these play out in radar rooms and control towers across the United States every day, all day. ATC training is a constant reality. If they’re not trainees themselves, they might be training someone else, or there’s training going on around them.

For pilots on the receiving end of a trainee controller’s, at times, less-than-perfect plan, it might seem like chaos. However, there’s a process at work, and safety checks involved to keep things from getting out of hand.

The Lay of the Land

Trainees at your average FAA ATC facility typically have widely varied backgrounds. Some are brand new, “off the street” hires with no prior ATC—or even aviation—experience. Others are ex-military veterans adapting to civilian traffic. There are also transfers from other FAA facilities. The latter may be climbing the promotion ladder, or—in some cases—controllers who didn’t make the cut at more complex facilities, trying out at an easier facility.

Aviation widely relies on the transfer of institutional knowledge. The flight instructor teaching you to fly didn’t acquire all his/her skills alone. Someone taught them the basics, who in turn was taught by another individual, and so on. Lessons from past experience (a.k.a. mistakes) enlighten future generations.

ATC is no different. Regardless of background, when a controller walks in the door of an ATC facility, they need to learn how to work that particular facility’s airspace. Achieving certification depends on the experience and guidance of the other controllers and staffers.

Like every aircraft type, every ATC facility is unique. The basic concepts remain the same—separate and organize aircraft—but the devil is in the details. If you learned to fly in Cessna Skyhawks, but are transitioning to a Piper Cherokee, the yoke and pedals work the same. However, would you automatically know to alternate between the Piper’s pump-fed fuel tanks periodically, after coming from a gravity-fed Cessna? Not knowing that may leave you high and dry during a cross country, attempting to air-start a fuel-starved engine.

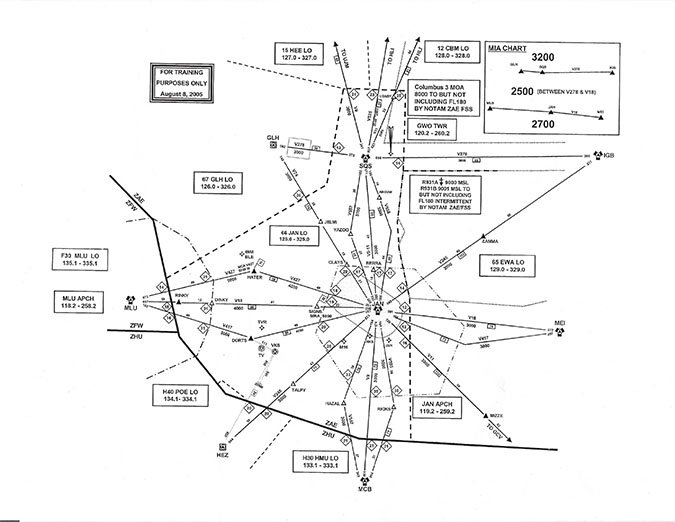

Before he gets anywhere near a frequency, an ATC trainee is expected to memorize a variety of documents specific to his new facility’s operation. Foremost are the facility’s airspace maps. Internal practices for that airspace are covered in Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs), and Letters of Agreement (LOAs) that detail how the facility interacts with other ATC facilities, aircraft operators, and government entities.

My first facility alone had nearly 30 LOAs with which I had to be intimately familiar. Wherever I’ve worked, I’ve been expected to draw the entire surrounding airspace from memory, replete with radar sectorization, frequencies, navaids, airways, radials, fixes, SIDS/STARS, and instrument approaches. It’s a lot to absorb, and there is usually testing and—depending on the facility—scenario-based simulation involved. Slackers don’t usually make it.

Zero to Hero

Book learnin’ is one thing. Separating aircraft is another. A pilot won’t learn to land in gusty crosswinds just by reading the Airplane Flying Handbook, and a trainee ATC won’t learn to manage traffic just by studying maps and regs. You’ve got to do it. A lot.

Sadly, no one starts off good. Frankly, it sucks being a fresh trainee. You’re plugged into a strange radar or tower position, simultaneously trying to speak in clumsy phraseology, recall your airspace and frequencies, follow new-to-you procedures, and do it all with a speed and accuracy that appeases the veteran controller plugged in with you. Every mistake is literally broadcast for 200 miles in every direction.

On the pilot side, new controllers can be pretty obvious: a quaking voice, vague or contradictory instructions, incomplete clearances, bad vectors. If you ever get a bizarre instruction from ATC, please question it. That said, some pilots can smell the fresh meat and will go in for the kill, with snide attitudes and vicious commentary. As a trainer, I’ve had to step in and stick up for trainees whose skin hadn’t yet thickened. “Training in progress, guys. Keep it professional.”

While improvement generally comes with time, some trainees may take longer to develop their skills. Adding to the pressure, each trainee has a limited number of hours within which to certify on each sector or tower position in the facility. For instance, in a tower, they may have 50 hours each for Clearance Delivery and Ground, and 100 hours for Tower. The goal is to get a recommendation from a trainer and be certified by a supervisor before hitting those limits.

All is not immediately lost for trainees who run out of training hours. They go to a Training Review Board, where a council of management and union representatives examine the trainee’s progress and interview their instructors and supervisor regarding their potential. Depending on the TRB’s analysis, a trainee may get more hours, a new set of instructors, or—if he’s already had a previous TRB at that facility—his training may be stopped. If it’s the latter, he may be transferred to a lower-level facility, or shown the door if he’s already had too many strikes.

As trainers, we’re not expecting our trainees to know everything. We’re looking for the temperament and judgment to step up and figure out the best course of action, even if it’s a situation they’ve never seen before. I’ve had trainees who could do only one thing at a time. One guy in particular could work a pattern of trainers, or work airliners in and out, but not both. Any abnormality would throw him off. In the end, he wasn’t successful at our facility.

Always Have an Out

So, what does it take for a controller to be qualified as an On the Job Training Instructor (OJTI)? It’s pretty straightforward: one year of full controller certification, a few days of classroom instruction, and then a brief session where they actually train someone under a supervisor’s watchful eye.

After that, they can start instructing on live traffic. Typically, they’ll start as a secondary (i.e. junior) instructor on a training team. That’s not always the case, though. I was the primary instructor for my first trainee, so I had to jump in there with both feet. When I started at my most recent facility, both my instructors were first-time OJTIs.

Documentation is stressed. Management monitors each trainee’s progress and hours via reports the OJTI fills out chronicling each training session, detailing what the trainee did correctly and where improvement is needed. The point is to recognize trends. For instance, if multiple reports show a trainee’s working speed and frequency knowledge isn’t up to snuff, we’ll push extra hard on those things in future training sessions.

A key thing for trainers is to not let a situation devolve to where we’re out of options. Complacency kills. Like a good flight instructor who always keeps his hands and feet ready to take the controls during critical phases of flight, OJTIs must know when to say the ATC equivalent of “I have the airplane.” When I train, my trainee is riding on my ticket. Any oversight can put my career on the line.

I had one trainee who was having an off day. His sky was black with airplanes—pattern, practice approaches, airliners, you name it. In the madness, he completely lost situational awareness, and turned to me, his wide eyes silently begging for help. I keyed up and issued exactly four vectors to four aircraft, and—bam—the planes were where they needed to be and the chaos was reigned in. We have to stay sharp and keep our cool even when a trainee loses theirs.

Be the Sponge

When a controller transfers from one facility to another, it’s back to trainee status. Prior experience is no guarantee of certification either. The distinct nature of each facility means that skills from one may not translate to another. I’ve seen controllers from insanely busy Class B airports struggle at lower-level GA airports. They could sling heavy metal in a highly structured environment, but couldn’t cobble together a VFR pattern to save their lives. On the flip side, a skilled, shoot-from-the-hip Cessna wrangler may struggle with those SIDS, STARS, and other structures that made the other guy feel at home.

It’s not just about relearning airspace and frequencies. It’s learning people too. ATC facilities feature tightly-knit teams of people with distinct techniques and idiosyncrasies, working out complex situations together. After years with my coworkers, I can tell when they’re going “down the crapper” just by their tone of voice or how they’re nervously tapping the “Clear” button on their radar’s keyboard. I know that my one friend likes having range rings up on her scope for mileage. Another colors all of his pattern guys blue to set them apart from white arrivals and departures. That insight doesn’t come overnight, but from time and perceptiveness.

Even when you’re certified, training never truly ends. In the downtime between sessions talking to aircraft, all controllers receive monthly safety briefings, computer-based instruction, and refresher training to keep them aware of regulatory and technology changes. Every little bit helps sharpen the “tools” and knowledge we use daily.

It reminds me of when I saw William Shatner—Star Trek’s Captain Kirk—speak at a convention last year. An audience member asked the 83-year-old veteran actor which he preferred: real science or science fiction. He replied at first by humorously speaking of scientific and historical books he had been reading, including one covering the remarkable intelligence of birds.

He then paused, feigning disgust. “Why am I acquiring knowledge? I’m going to die!” he said, in his self-deprecating fashion. “I’ll be in the ground, and know that birds are intelligent? What difference does it make?” He suddenly grew serious. “To answer your question: I love entertaining. I love acquiring knowledge. If I acquire knowledge, I can put it into fictional form, and maybe entertain you with the knowledge I acquire.”

The octogenarian actor recognized a fundamental truth: a person is never too old to learn, or to apply that new knowledge to improve themselves and the career they’ve chosen (in his case, entertainment). That’s especially crucial in aviation, where planes fly fast and the rules and technology can sometimes change even faster. Whether as a trainee or trainer, in air traffic control, learning is a constant. All we can ask of pilots is that they be patient with us as we teach the new guys to serve them better.

Cultivating Confidence

Confidence is essential in ATC, and can’t really be taught. A trainee needs to acquire it on his/her own. But, that doesn’t mean we can’t help along the way.

I was training an individual with serious confidence issues. His previous trainers had grown frustrated with his lack of progress. I took over his instruction. I knew he had the knowledge and potential. But, he didn’t know it.

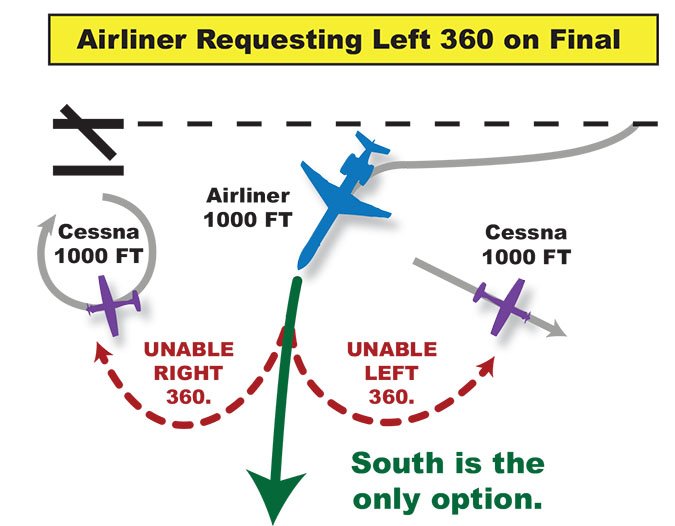

In one of our first sessions, we had an airliner inbound on a visual approach to our westerly runway. He was kind of high and asked for some S-turns, which my trainee approved. There were two Skyhawks in the vicinity: one southeast of the airliner, departing our airspace, the other southwest of the airliner, making 360s in the left downwind to follow the jet.

The airliner widened out to the south. Still too high, the airliner’s pilot said, “We’re going to need a full 360.” I looked out the window. He was already deep into the left turn, at 1000 feet. The Skyhawks bracketing him a mile southeast and southwest of him were also at 1000 feet. My trainee stammered, “Uhhh, standby.” Crap! He’d frozen.

This was no time for “standby.” If that jet continued left, he’d hit the outbound Skyhawk. Right was no better with the Skyhawk in the 360. I took him due south—directly between the Skyhawks—and sent him back to Approach for resequencing. My trainee didn’t trust himself to fix the problem quickly and had overthought it, losing precious time. It wasn’t the first time he’d done so.

After that session, I sat down and developed a training regimen for him. I created bizarre scenario after bizarre scenario, and threw them at him in simulation and discussion: emergencies, strange requests, pilot deviations, bad sequences from other controllers. Even as we trained on live traffic, I would constantly throw “what if” situations at him.

For weeks, we did this. The intent wasn’t to show him all possible scenarios; that list is infinite. I wanted him thinking rapidly and creatively, to believe he could fight his way out of complex, volatile situations. It started paying off in his performance and speed. He wouldn’t overthink. He would act decisively.

Four months after we started, and via the stroke of our most hard-line, skeptical supervisor’s pen, this trainee became a certified professional controller. He just needed to believe in himself. To get to that point, he needed to be pushed out of his comfort zone and be trusted that he could handle it. —TK

Even after training dozens of controllers throughout his career, Tarrance Kramer knows he’s still got much to learn, and that’s something worth teaching.