With all the distractions in the cockpit—whether it’s loading the navigator, copying a clearance or simply dropping the only pen you brought along—it’s no surprise that close calls on the ground are still common. Perhaps not surprising, but not acceptable either. After all, we have a lot of tools to help us remain safe on the ground. We’ve had ground-safety procedures drilled into our heads in recent years. GPS is common now for taxiing, along with lots of signs and lights to guide us. So runway incursions and related incidents ought to be on the decline. As it turns out, though, things haven’t improved.

Stats Are One Sign

If we look at the reports of recent years studied by the FAA, we’ll see that there have been well over 1000 runway incursions annually and, with flight hours on the rise, those totals are going up. The FAA defines runway incursions as “any occurrence at an aerodrome involving the incorrect presence of an aircraft, vehicle or person on the protected area of a surface designated for the landing and takeoff of aircraft.” This is a separate category from “surface incidents,” which occur in the areas of the airport other than runways, such as taxiways and ramps.

The FAA has a severity scale for incursions, going from D (an “incorrect presence” without any safety risk) to A (a close call). Beyond that, it’s an actual collision.

Each incident also falls into categories to suggest the cause, including Operational Incidents (ATC loss of separation), Pilot Deviations (self-explanatory) and Vehicle/Pedestrian Deviations.

In 2013, there were 1242 runway incursions. These included 243 operational incidents, 783 pilot deviations and 212 vehicle/pedestrian deviations. (Note: The agency’s numbers go by federal fiscal years, which run from October through September.) In 2014, there were 1264 incursions; 2015 saw 1458, and 2016 had 1557 incursions. Within those totals, pilot deviations make up the majority, increasing to 942 in FY 2016.

And these are just the reported incidents. It’s fair to say that at least a few thousand more incursions occur at non-towered airports. Anecdotally speaking, these occurrences are somewhat different because it’s the pilots who make their own taxi routes and decide when it’s safe to cross runways, when to hold short and when to taxi onto or across intersections. So close calls tend to appear in the form of back-taxiing on runways with an aircraft on final approach, aircraft departing with other traffic still on the landing roll or someone trying to speed across a runway while another aircraft is on a takeoff or landing roll.

You’ve Seen ‘Em

Most of you have seen at least a few of these examples and you might even have been involved in an incursion yourself. According to the FAA, most reported pilot deviations are the result of not holding short of a runway when instructed to do so.

The runway incursion problem is a particularly frustrating safety issue because they are highly preventable. They occur mainly from loss of situational awareness and distractions in the cockpit. The main causes of that loss of situational awareness continue to be confusion in communications, confusion in taxi routes and simply failure to see other traffic.

One close call that spurred the FAA’s recent focus on runway safety involved a Cessna Skylane and a King Air at Daytona Beach International Airport (KDAB) in 2007. The incident occurred because the Skylane, cleared to taxi to the N5 intersection of Runway 7L, entered the runway as the King Air was accelerating down the runway on his takeoff run.

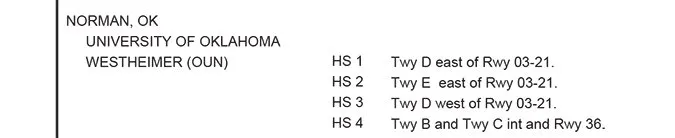

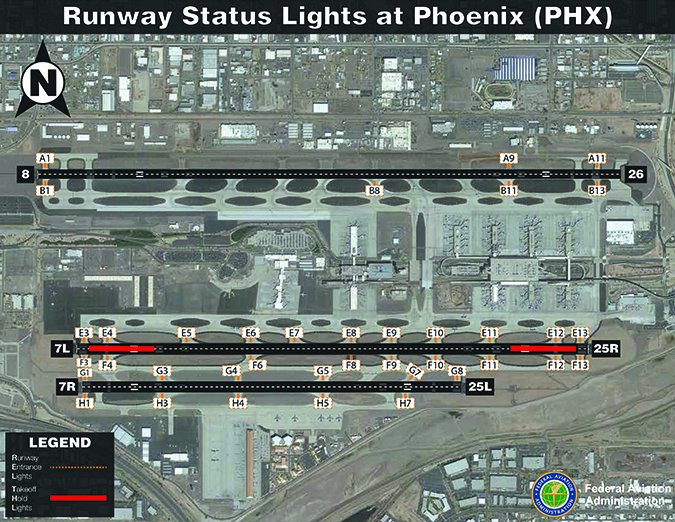

Not long after this event, the FAA ramped up educational and outreach efforts and began adding “Hot Spot” designations and descriptions to airport information to highlight specific places that have had repeated incursions or are at particularly high risk for them. (See the airport diagram to the top right of the page.)

A key takeaway from these efforts is that most incidents are preventable and share common causes. So, why are incursions still occurring so regularly? On top of the communication and situational awareness challenges, perhaps complacency is at the root of most incidents. Ground operations can get more complicated than we recognize and we tend to get lax on the ground, rather than exercise the vigilance and attention to detail that we exhibit in flight.

There’s a similarity here to driving your car. Minor fender benders are more common in parking lots—where traffic flow is less predictable—than on city streets. The same is true of aircraft on the ground at airports, where traffic is going to/from the fuel island, to/from hangars, to/from transient parking, etc. Keep this in mind as we review some basic preventive practices.

Listen Up And Copy

Exercising collision avoidance on the ground starts with careful listening. While warming things up after engine start, and before releasing those brakes, we’ll normally pick up ATIS or the AWOS. Take an extra moment at this point to briefly monitor ground control or the common traffic advisory frequency so you know what to expect for taxi routes and/or departure runways in use.

You can even note the taxi routes that others are getting so you can be on the lookout for potential conflicts or simply to be prepared in case you get something similar. But don’t let that become fixed as an expectation in your mind, possibly causing you to miss a difference.

Even if you do get something similar, you can certainly ask for something different if it suits you—whether it’s for an intersection departure or another runway so you can work on your crosswinds. Never release your brakes until you’re sure exactly where you’re going; don’t assume you’ll figure it out on the way.

As always, seek clarification if anything is unclear; don’t wait ’til you’re on the move and wondering if you were supposed to turn onto Juliet or Kilo at the intersection.

Another thing to get down before taxiing is to know for sure which runways you’ll encounter and cross-check for the appropriate “cross” or “hold short” instructions. As of June 2010, the regs changed to require specific instructions to cross runways, rather than allowing pilots to assume the taxiways in use are also for crossing. No longer does an instruction to taxi to a runway give you permission to cross intervening runways. Each runway crossing must be explicitly granted, but can be granted all in the initial taxi clearance.

Oh, and the controller must get a readback of hold short instructions. If you’re at a non-towered field, it’s a good idea to announce where you are and where you’re taxiing; when crossing runways, say so to help others with their situational awareness.

Hey! Heads Up!

Paying close attention can prevent accidents, even if an operational or pilot error has occurred. Having a head down in the cockpit to set up radios (or even check an airport diagram on an iPad) has caused many an incident. When taxiing, keep your eyes outside and move at appropriate speeds so you have plenty of time to look ahead and clear the area in each direction when making turns or crossing intersections.

Along with keeping your head up, you should be scanning to the sides and looking down the surface in front of you. Read and assimilate the information on every sign.

When the visibility is low, emphasize what’s down in front of the aircraft, where you’ll find enhanced taxiway centerline markings showing you’re approaching a runway. Increasingly, airports have runway signs in red boxes painted right on the taxiway surface to alert you to the hold short line ahead.

Never assume that a clearance to take off means there isn’t traffic there. Scan the final course as you’re reading back your clearance, and when lined up on the runway centerline, scan ahead down its length for any stragglers or wayward vehicles. (I once declined a takeoff clearance, replying to tower that I thought I might wait for the landing traffic to clear. Turns out the controller misspoke, meaning to tell me to line up and wait, instead of clearing me for takeoff. —FB)

When preparing to depart a non-towered field, be sure you visually check the pattern and final approach path, plus the full length of the runway itself. And when on approach, do the same—check the full length of the runway and make note of anyone holding short at the threshold or on an intersecting taxiway to make sure they don’t start moving out towards a potential incursion with you.

The Landmark Accident

The collision of two Boeing 747s on the ground at the Tenerife, Canary Islands airport in 1977 remains the world’s deadliest aircraft accident. A chain of circumstances including usually heavy airport activity, an impatient captain, heavy fog and lack of ground radar led to 583 deaths.

Gaps in communications were the final link in the chain as the crew of Pan Am Flight 1736 tried to transmit they were taxiing down the runway as KLM 4805 was unknowingly starting its takeoff without a clearance. Plus, there was confusion about what ATC knew about the position of each aircraft as visibility made it impossible for the tower to see them.

The accident led to the implementation and enforcement of many of the best practices we take for granted today, such as improved standardized phraseology. (e.g. The word, “takeoff,” can no longer be used except in actual takeoff clearances.) It also sparked changes in cockpit culture, known as Crew Resource Management, to emphasize communication among crewmembers along with mandatory use of standard operating procedures.

Use The Lights, Or Not

Let’s talk about using lights for ground operations. During the day, about half the pilots prefer taxiing with lights on and half who prefer them off. While it’s not required, some recommend lights on when moving around as it adds one more way for you to be seen—unless, of course, lights interfere with others’ ability to see. (In crew operations, pilots will turn them off as a way of signaling they’re giving way and/or holding short. While this also is a good idea, it does not always ensure that other pilots are clear about your intentions.)

At night, taxi and/or landing lights are obviously needed, so they’ll nearly always be on unless they’re problematic. When taxiing into a well-lit ramp area where people are marshaling you in or walking around, it’s usually best to switch off your lights to avoid blinding others.

The Airplane Flying Handbook appendix titled “Runway Incursion Avoidance,” recommends all lights on for takeoff and runway crossings day and night, with everything but the landing light for taxiing and entering runways.

Regardless of what you decide about using “daytime running lights” on your aircraft, if you choose to use your lights, be aware of others and be quick to turn lights and strobes off when they could interfere with other ground operations.

Ground operations have just as much complexity and risk as flight operations in terms of planning, regulations, cockpit resource management, and ATC communications. So as with any phase of flight, good procedures and vigilance are essential.

Elaine Kauh is a CFII in eastern Wisconsin. She has always written down taxi instructions, even in winter with gloves on, and can usually read her own writing.