Non-towered Longmont Airport (KLMO) had one RNAV 28 instrument approach. It’s not unusual to have five airplanes in the pattern. On this particular VFR day, one was lifting off from a touch-and-go, another was on crosswind, the third neared midfield downwind, another turned from downwind to base, and another airplane was on short final. In addition to the airplanes in the traffic pattern, there were two aircraft practicing approaches on the RNAV 28 approach. One RNAV pilot was flying to minimums followed by a circle-to-land. The other pilot was flying to minimums and continuing for a touch-and-go landing.

Who has the right-of-way—the traffic pattern aircraft or the RNAV approach practicing aircraft? The AIM is very explicit on how to enter a non-towered traffic pattern. However, the AIM, based upon my research, doesn’t address the synchronizing of traffic pattern aircraft and practicing instrument approach aircraft.

I turn to the bottomless depth of knowledge of the IFR Magazine experts for guidance and an answer.

Bruce Thompson

Denver, Colorado

“Bottomless depth of knowledge,” eh? Not so sure on that one!

You’re right. The regs and AIM are essentially silent on mixing instrument traffic (real or practice) with VFR traffic patterns. What’s that tell you?

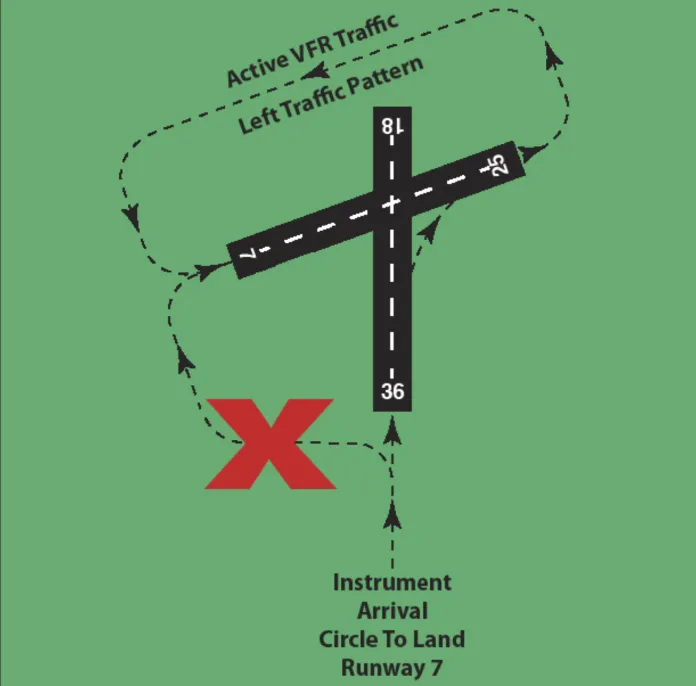

It tells me that it makes no distinction. Only the published right-of-way rules apply. Note, though, that recently the FAA has made a bit of a point of saying that IFR traffic must follow existing patterns and traffic flow. So, for example, say you’re on an instrument approach to Runway 36 (landing north) but the winds favor Runway 7 (winds from the northeast) and there’s VFR traffic in the normal left-traffic pattern for 7. What’s the aircraft on the instrument approach to Runway 36 to do?

First, you could probably just land if the wind isn’t howling. But, with traffic using Runway 7 (intersecting runways), that’d potentially be suicide. So, you opt to circle to Runway 7. Which way? Well, a circle to right base for Runway 7 would be simple and obvious … and wrong. The airport uses left traffic. So, the instrument traffic must also use left traffic. In that scenario, I’d recommend simply joining upwind for Runway 7 and fly all the way around—left crosswind, downwind, base, final, to Runway 7.

Many instrument pilots tend to innocently and incorrectly assume that they’ve got right of way in VMC, especially if they’re on an instrument flight plan. No, they’ve got to fit into the traffic pattern just as if they were VFR traffic approaching to land. The regs and AIM don’t leave room for anything else.

I recall once approaching my home airport to land. I was above a solid cloud deck, but it was (minimally) VMC below. I was on vectors and punched through the deck only to find a Champ filling my windshield about 50 feet below the ceiling close ahead. Oh, $#!+. I broke off and pulled in behind him. I made all my traffic calls on Unicom, but never heard the Champ. I figured he had no electrical system, but most similar aircraft at that busy non-towered airport at least used handhelds. He continued to his landing, on the way making an extremely tight, close-in base leg and cutting off traffic on final, making them go around. I simply followed and watched incredulously.

After landing, I stopped at the end of his hangar row and walked down to where he was putting his bird away. I tried in my best friendly-pilot demeanor to talk to him. I introduced myself and asked if he knew he’d at least cut me and the final traffic off. He shrugged, not caring. I asked if he’d considered using a handheld radio to avoid such happenings and he said, “A friend of mine gave me one. I tried using it but it was always squawking and it was just a distraction. I don’t use it any more. That’s it over there on the bench.”

I was tongue tied, so I just said goodbye and walked away. Who was wrong there? Well, clearly he was for not maintaining VFR cloud clearance and for not yielding right of way to the final traffic. But, how can you yield if you don’t know traffic is there? He had every right to fly into a non-towered airport with no radio and it was up to everyone (not just him) to see and avoid. And, even though I was legally descending through the cloud deck on an IFR flight plan, once in the clear, avoidance of traffic was my responsibility.

Moral of the story: It may be a big sky, but there are a lot of small sandboxes where we all play. We’ve got to play together nicely in the sandbox.

—Frank Bowlin

Illogical Failure Fix

In your January issue, you ran “Illogical Failures,” a sidebar to the article, “Ice is Not Nice” from Fred Simonds. In it you explained how in some EFIS a simple pitot or static failure could render gyro information unusable. You then discussed how some of the EFIS manufacturers are working around that.

You mentioned that Aspen developed a GPS-based fix for their Max regarding those past issues. An Aspen representative assured me today that the same fix is currently incorporated in the less expensive E5.

William Kelly

Palmdale, California

Good information, William. Thanks.

Which One Is Correct?

Many of our GA airplanes now have two altimeters: an electronic PFD like Aspen, Avidyne, or Garmin indicators, and the requisite standby, be it the original round dials or another electronic instrument. If we discover on run-up that the altimeters are off by more than 75 feet, what actions must the pilot take, if any?

Kirsten Newbury

Lake Oswego, Oregon

I don’t have a clear-cut answer for you. Like so much in aviation, I’d say that part of the answer is, “It depends.” Are you flying VFR or IFR? Will you be flying moderately low or up in the flight levels? The issue is simply what difference between multiple altimeters is acceptable?

The first source for an answer to your question should probably be the EFIS AFM supplement(s). You might well find the exact answers you require. But for the purposes of this discussion, let’s assume the supplement(s) is/are silent on the point. So, we’re forced to reason through this.

First, if VFR, I’d say go fly. Also, if IFR but relatively low you might also consider launching, so long as the difference remains nominal, say under 100 feet or so. But, what is the nature of the error? Is it a fixed offset, or does it scale? For example, if it’s a 75-foot difference at sea level, at 10,000 feet or even 20,000 feet is it still 75 feet, or is it, say, 300 feet? If it scales (increases with altitude), my thought is that the cause of the difference needs to be investigated before serious IMC flight at altitudes where the difference exceeds 100 feet or so. But, if it’s a fixed offset staying around 75 feet, again you’re probably safe to go flying, even in hard IMC.

My airplane actually has three altimeters: the EFIS PFD, the standby, plus another EFIS PFD on the right side of the panel. I remain aware of the altimeter differences and, so far haven’t had any issues. But with three, I have the advantage of taking a vote. If two of them remain close, it’s likely that those can be trusted and there’s a problem with the third. I actually was faced with this once when I was flying for the airline.

We’d gotten vectored through some extremely heavy rain. “Ding!” We got an annunciation that the difference between the left and right altimeters exceeded the threshold. In addition to the left and right EFIS PFDs, we also had a standby instrument. Our procedure was to crosscheck to determine the problem. My altimeter read, say, 15,000 feet. The first officer’s altimeter read 15,250. Then, checking the standby instrument for the tie breaker, we found that it read … zero. Okay, the book didn’t cover that, so judgment was required.

Thinking about it for a moment, I decided to trust my altimeter. It read lowest, so even if we were higher, using that lower altitude was safest. We reported the malfunction to ATC, got more vectors, and ultimately got cleared for the approach. We broke out well above minimums and landed visually. Once at the gate, we wrote up the problem. Subsequently, maintenance drained almost a quart of water total from the three pitot systems.

Bottom line here, and my point, is that ultimately we’ve got to use our judgment. If the book is clear, good judgment requires following it. But, still, the pilot in command is responsible for the safe outcome of the flight and judgment is an element of most everything we do, especially when the book is of no help.

I know this doesn’t directly answer your question, Kirsten, but hopefully the discussion is of help.

—Frank Bowlin

Which “These”?

In April’s “The 5G Brouhaha” the last sentence of the opening paragraph says, “…these are now typically only found in far more complex aircraft.” For the life of me I cannot determine to what “these” refers.

We goofed. Something got lost in the editing and layout of the article. The retrofit being referenced is a radar or radio altimeter.