Just like pilots, controllers get plenty of questions, comments, concerns, and sometimes complaints. Bonus: Writing these articles gives me an opportunity to address some items in print. Of course, I’ve dealt with my share of good and bad remarks on and off frequency. It’s not at all unusual for a pilot to wonder; “What is going on in that Tower?” It’s okay to think that; sometimes we think the same thing about pilots.

Opposite Direction

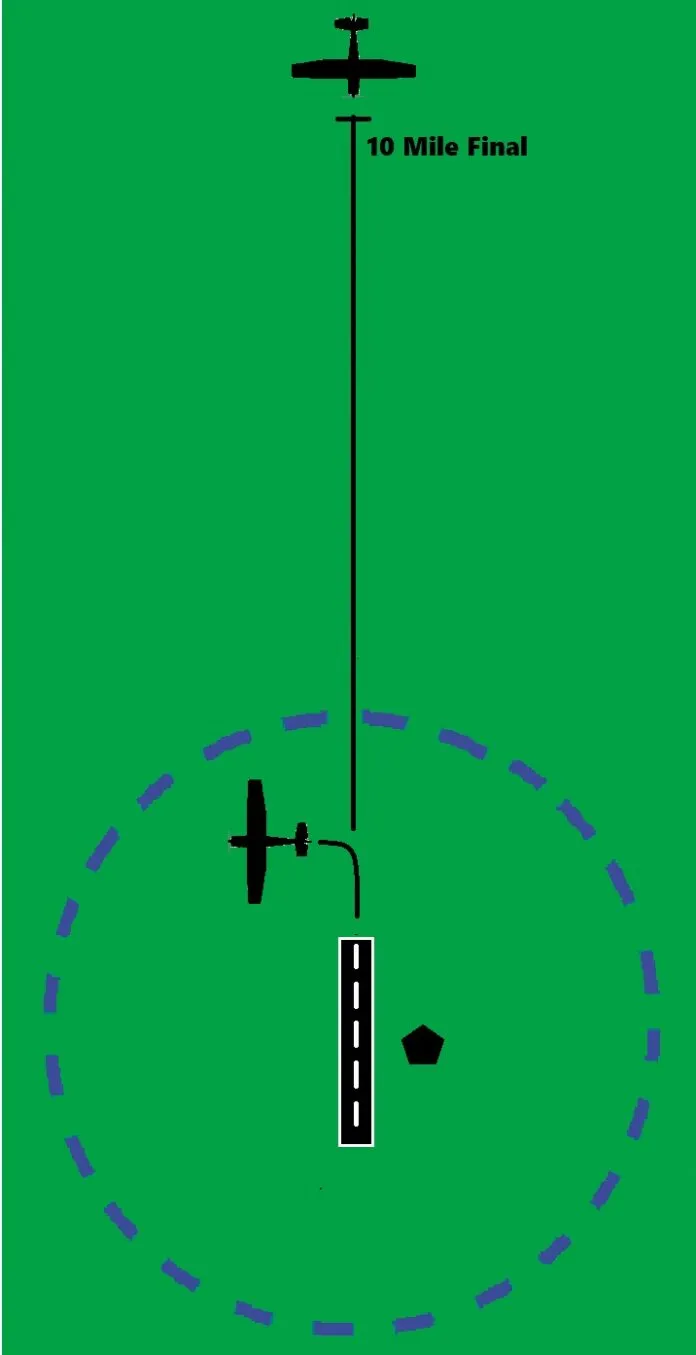

Imagine you are at a small towered field, Class D, and about to taxi out for an IFR departure in your 172. It’s a beautiful VFR day and you are only flying about 40 miles away. You might question why you filed IFR. Nonetheless, you taxi out to the runway with your clearance, complete the runup, and call Tower, “Ready for departure…” Tower replies, “Hold short, Runway … I have opposite-direction inbound IFR traffic.” You think it’s probably only a couple miles out and shouldn’t take long.

After five minutes you ask Tower, “How much longer?” They respond, “Oh it’ll be a few minutes. The opposite-direction traffic is not at the IAF yet.” At this point you decide that going VFR will be more advantageous than waiting over 10 more minutes. “Tower, we’d like to cancel the IFR and depart VFR.” Tower responds, “Roger. Hold short for arrival.”

There was nothing else going on, not even a normal-direction arrival. You drink some water before your head explodes and wonder why this controller is giving you the worst service ever, but wonder at the same time if he is justified. You definitely could’ve taken off and turned well before that opposite-direction arrival—another 172—came anywhere close to the airport.

My first response to this scenario is surprise. I would never have done that, and would be very unhappy with that service. But the rules vary between airports. For example, some airports in the mountains don’t allow any opposite-direciton activity, while airports in the south flat lands do it all the time. The base order for opposite direction operations (JO 7210.3CC, 2-1-36. currently) dictates that the facility directive must have this spelled out, so there is baseline.

In many Class D towers in the south, the LOA spells out 10 miles IFR/IFR (departure turned before inbound reaches 10 miles) and in some towers, that includes a four-mile cutoff for IFR/VFR (VFR turned before IFR reaches four miles). It all depends on that LOA, but if that tower had one similar to the rules above, there should’ve been no problem getting the IFR 172 out, and even less problem if the 172 was VFR.

At my airport, the Tower has to authorize opposite-direction arrivals, while the TRACON is the one who authorizes opposite-direction departures. If it were an opposite-direction IFR arrival versus a normal IFR arrival, whichever is first has to be on the ground before the other reaches 10 miles.

Runway Separation

We’ve all heard that there is a big difference between legal and safe. In the air it could mean, “How close can I get to that other airplane?” and toward the ground it means, “Can I land with that guy still on the runway?” There’s a fine line for pilots that balances comfort, skill, legality, and safety. Let’s look at this scenario from two angles.

You are a low-time CFI flying with a student practicing landings at a Class D airport. You end up following a similar type airplane and do multiple laps in the pattern. The airplane in front tells the tower they’re full stop, but you want to keep going. They are cleared to land while you are cleared for the option. Let’s say both airplanes are PA28s. The airplane in front of you lands and is slowly exiting about half-way down the 8000-foot runway; you’re on short final, full flaps, at 70 knots. Uncomfortable landing with another airplane on the runway, you go around. Why didn’t Tower tell you to go around?

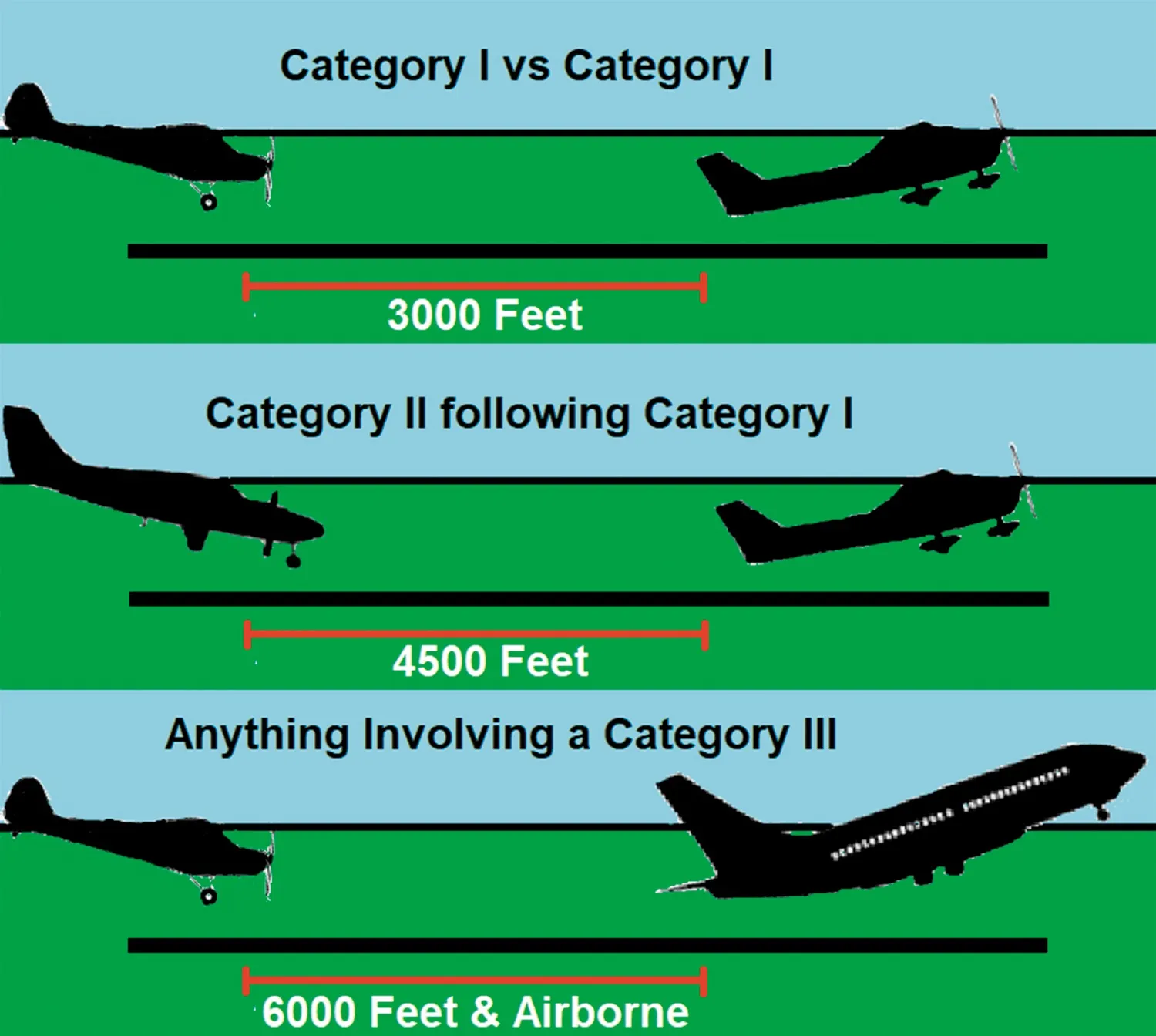

In the airplane, why did the CFI believe it was unsafe to land? Inadequate training? Inexperience? Overabundance of safety? I’ll leave those questions to you. From the tower perspective, there was nothing illegal in the scenario. Assuming the airport/runway had suitable landmarks (runway distance remaining markers, for example), standard separation between a PA28 and a PA28 (both Category I aircraft) would be 3000 feet. It’s very common to have a line of single engine pistons (under 12,500 pounds) wanting to depart, and launching one after the other. It’s literally cleared for takeoff, wait for airplane to roll, number 2 cleared for takeoff, etc. For those readers who have never been to Oshkosh at the end of July, that 3000 feet is reduced to 1500 feet with special permissions.

Line Up and Wait

I had a pilot come across an interesting situation at a nearby airport and he came to me asking about procedural right and wrongs. He was flying his RV-7 and was holding short ready to depart while a C-130 was landing. Tower told him to line up and wait and he complied. A minute later the C-130 exited the runway and the tower cleared him for takeoff and proceed on course. He then responded with, “I’d like to wait for the wake to dissipate, do you need me to exit?” Tower responded with, “Cleared for takeoff your discretion.” I was surprised when he told me this for a few reasons, but the main one was cleared for takeoff at pilot’s discretion. I’ve never heard that before, nor would I ever give that instruction.

I explained to him that in my opinion there were several things wrong in that scenario. First, wake turbulence stops when lift is no longer generated (aircraft touches down). There would have been very minimal wake to pass through, if any at all with the C-130 taking forever to get off the runway. Then I asked him, “Why would you accept a LUAW clearance if you weren’t ready for departure?”

The question stopped him in his tracks. I’m sure it was not ill will; however, LUAW is not intended for aircraft to sit on a runway until it is convenient for them. If this ever happens to me, I would definitely ask that question right after I tell the aircraft to taxi off the runway. Most simple mistakes in aviation can be fixed as long as they are spotted early on, even in ATC.

VFR Headings and Altitudes

Here is one I’m sure most pilots run into occasionally. You’re flying VFR with flight following in Class E airspace. You start getting traffic calls for opposite direction traffic so you start looking. The controller then tells you to turn to another heading and maintain a different altitude. You reluctantly reply and then comply. Shortly after, ATC says, “traffic no factor, resume own navigation.” You comply. Then think, what the heck, why did they do that? We are VFR in Class E. Why not just update us on the traffic and let us avoid as necessary?

Honestly, it’s not the worst inconvenience when on flight following. By asking for flight following, you are asking for traffic calls and in some cases vectors around traffic. In Class Bravo airspace, you can expect specific headings and altitudes from ATC, and ATC expects you to comply. Anyway, the reason they might turn one (most of the time the VFR one) is because they have the responsibility to separate aircraft.

I’ve done it in the tower plenty of times. I would have two airplanes going right at each other while I call traffic, and they still aren’t finding each other. I’m not going to shrug my shoulders hide behind VMC. Nope; I’m going to turn one with a suggested heading and maybe even throw an “immediate” in there. We are not fans of watching targets merging and not doing anything about it without special circumstances, like not talking to them or military in an MOA.

I’ve prevented what could’ve been a midair collision more than once. After those occurrences, I normally get a “Wow that was close; thanks.” There could be plenty of reasons they couldn’t find each other, but we’ll debate on the ground.

Student Pilots

Last one we’ll talk about involves student pilots. A student pilot was coming back from a cross-country flight to a busy Class D airport. The student was told to report over a landmark about four miles south of the airport, while a jet was told to report a left downwind and another given a right downwind report. They all complied, except for the student. Upon arriving at his designated point, the student started to climb and descend in circles.

The controller saw this and asked if he was okay, and the student replied that he was fine and over the reporting point. The jet in the left downwind was turning base and told about the traffic (student), then the student was told about the jet. The student pilot then turned and flew directly at the jet.

ATC instructed the student to turn away and circle the reporting point, but he did not comply. The jet ended up turning his base tighter than normal and exclaimed, “Keep that guy away from me!” The controller wasn’t sure what was happening, but wondered if there were other issues. He instructed the student to finish his circle and come straight in to land. The student replied and complied.

ATC then told the traffic in the right downwind to make a left 360 and that he would be number 2. ATC then told the student he came very close to that jet, and asked why? Student replied with, “Understand number 2 follow jet.” With what sounded like an ESL student, ATC clearly told him he could’ve hit another airplane, and he needed to be more careful. The student didn’t respond and landed without incident.

A few hours later, the student’s CFI called the tower. “Why did you yell at him in the air? Why not wait until he was on the ground? There are better ways to handle it. I have 300 hours…” etc. Well, I’ll explain why.

A few hours later, the student’s CFI called the tower. “Why did you yell at him in the air? Why not wait until he was on the ground? There are better ways to handle it. I have 300 hours…” etc. Well, I’ll explain why.

The student wasn’t deviated, but he did call the tower after landing and got another firm verbal warning. There are mixed opinions on whether it should have only been done on the ground or while in the air.

I’ve found that it makes a bigger impact on the students when you tell them as soon as they screw up. Telling the student as soon as he was listening, “Hey you almost crashed into another airplane and died,” has a bigger impact while still in the air. If the student actually heard what ATC said, it might make him more nervous, but it will wake him up to the fact he should not repeat this action.

We Will Adapt

There are countless scenarios of learning lessons for both pilots and ATC. With advances in technology, science, and aeronautics come changes in training methods. An airplane with a six pack has a completely different ground school than with a G1000. Similarly, ATC didn’t have to worry about 5G interference before. Now we have to receive training on “what if” scenarios. We’ll just keep on trucking … I wonder if there will be a “Space Traffic Control” happening anytime soon.

When necessary, Elim Hawkins will do things repeatedly until they are done correctly. There is no point in putting in all the work for something to be wrong.