When my wife and I were shopping for our first home, we came across this great little 3/2 “starter” that fit our needs well. I remember walking around the fenced yard, surrounded by tall trees in their pretty autumn colors, enjoying the quiet. Fortunately for us, somebody outbid us.

Behind that fence and those trees lurked a runway that was closed for lengthening. Six months later, that home’s new owners were less than a quarter mile from the runway’s newly opened threshold. All day, every day, their once-peaceful yard was filled with the roar of everything from of B-757s and military fighters, to the pervasive piston drone of flight school trainers.

As an air traffic controller, pilot, and lifelong aviation fan, I do love airplanes, but there’s definitely truth to the “too much of a good thing” clich. We dodged that bullet and eventually found another home a few miles away where planes and nearby highway noise faded together into the background.

I can’t imagine that first home’s owners trying to enjoy their yard, get some work done, sleep in, or sometimes just have a simple conversation. The fact is, aviation noise affects people’s quality of life, and it’s up to the FAA, airport operators, ATC, and, in turn, pilots to reduce that disruption as much as practical.

Airport Design

Airports are usually born in the lesser-populated outskirts of their namesake town. Over time, they often find themselves enveloped by suburbs and industry. This close contact inevitably leads to tension, as city populations and aviation traffic demands grow in parallel, spurring a need to reign in the noise.

Noise abatement often begins with “good neighbor” policies—typically voluntary, common-sense practices designed to assuage the locals. It’s vital that controllers and pilots adhere to these practices the best they can. The Chart Supplement (A/FD, if you missed the name change) doesn’t detail many of them; you’ll have to search the web or call the airport itself for details.

There are as many combinations of restrictions as there are airports. Palm Beach County Park (KLNA) bans all touch-and-go traffic from 10 p.m. until the morning. Camarillo airport in California (KCMA) requests that any departures between 12 a.m. and 5 a.m. have the airport director’s approval. Pensacola, FL (KPNS) urges pilots to depart on Runway 8 out over the water. Miami Executive Airport (KTMB) prohibits departure turns below 1000 feet.

For jets over 75,000 pounds, many airports urge pilots to use Noise Abatement Departure Profiles (NADPs). There are two detailed in FAA AC 91-53. A Close-in Community NADP is “intended to provide noise reduction for noise sensitive areas located in close proximity to the departure end of an airport runway.” A Distant Community NADP has less stringent requirements since the noise-sensitive areas are further away. Each specifies thrust settings, speeds, lift device settings, and altitude goals, all designed to maximize climb rate and minimize disturbances.

Controllers are trained to minimize noise as much as possible. I’ll frequently coordinate jet departures after dark to climb straight out to 10,000 feet. We also work with airport restrictions, such as keeping helicopters away from noise-sensitive neighborhoods just outside the airport. When I’ve got night touch and goes going on, I’ll try to keep their pattern on the terminal side of the airport, opposite those same neighborhoods.

Airports are noisy places, and local residents for the most part understand that. As long as we—both controllers and pilots—respect voluntary noise guidelines, things might stay voluntary.

Growing Planes

An airport is a living thing. As its traffic changes, so must it, to match its customers’ needs. More ramp space and terminals? More runways? The lengthening of runways for larger—noisier—aircraft? These necessities are real, and a crowded neighborhood means the airport will likely have a fight when it wants to expand and change flight patterns.

Airports are major pieces of infrastructure that greatly affect a city’s economy by providing jobs and bringing in business. While an inconvenience to neighbors, an expanded airport positively impacts both the city’s big picture, and the nation’s. An airport at capacity ripples its delays across the system and, sooner or later, expansion is inevitable.

That doesn’t mean construction begins without consideration for surrounding areas. Any significant, modern airport expansion project requires impact studies that examine possible effects on local communities and the natural environment. Noise is an enormous concern, often requiring concessions.

Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport (KFLL) lengthened its shorter runway, 10R/28L, to accommodate large airliners. Nearby houses under the flight path had soundproofing installed on the city’s dime. According to a 2011 Sun-Sentinel article, between new doors, double-pane windows, roof insulation, and air conditioning units, the airport was spending about $65,000-$75,000 on each of the first 48 houses.

Unfortunately, the runway’s construction outpaced soundproofing for over a thousand homes. In 2013, the year before it opened, there were only 174 noise complaints. After the runway opened in 2014, distressed residents filed a storm of complaints and lawsuits. Between January and July of 2015 alone, according to the newspaper, there were 4274 noise complaints. The anger is real.

Making Accommodations

The powers that be aren’t deaf to those complaints. Working with the airport authority, the FAA and its air traffic control experts figure out how to balance efficient air traffic services with the curtailment of noise pollution. This demands copious amounts of data.

First is an examination of the airport’s surroundings. Industrial areas are far less susceptible to noise since most businesses close at night and are less densely populated throughout the day. Most complaints come from residential areas after dark when people are trying to relax in their homes. The “duh” takeaway: Avoid densely populated areas.

Then there are noise metrics. Many airports utilize noise-monitoring systems that analyze ATC radar and data from noise sensors around the airport. Westchester County Airport (KHPN) in New York has 22 permanent sensors. Fort Lauderdale uses 11 sensors monitored by a full-time noise officer. These systems record, recreate, and visualize noisy flight paths and aircraft.

With data in hand, traffic flow can be modified and new procedures can be created. At Fort Lauderdale, ATC implemented new procedures on August 3, 2015 that knocked noise complaints down from 977 in July to “only” 629 in August. What changed? Runway 10L arrivals and 28R departures were prohibited from turning below 3000 feet and were kept over the nearby, already-noisy Interstate 595. Eastbound departures were routed three miles out over the ocean before turning.

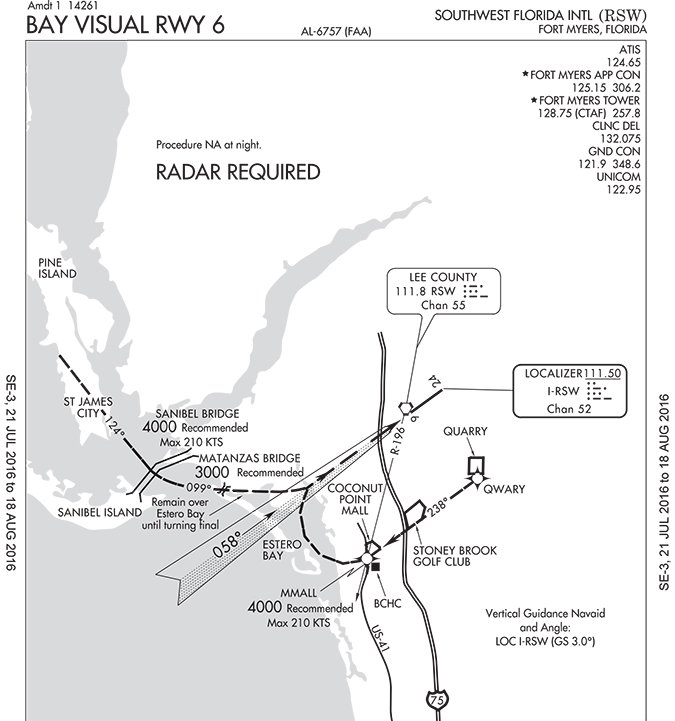

The above requires manual vectoring by ATC. For clarity and ease, some airports develop specialized visual approaches called Charted Visual Flight Procedures (CVFPs). As detailed in FAA Order 7110.79D, CVFPs establish visual landmarks over which traffic must fly to avoid noise-sensitive areas. It’s basically a visual approach over visual waypoints.

A CVFP clearance requires that the pilot report either a CVFP landmark or the preceding aircraft in sight. Then, the approach’s name must be stated in the clearance: “N3BA, cleared Bay Visual 6 approach.” There are also key environmental factors: There must be an operating control tower, the ceiling must be at least 500 feet above the minimum vectoring altitude, and visibility must be at least three miles.

From Screams to Whispers

Noise abatement isn’t just about controlling where and how aircraft are allowed to fly. Aircraft designs themselves are key to the whole thing. Airliners in particular have become exponentially quieter since the first large jet transports were introduced in the 1950’s. Over time, shrieking turbojet engines gave way to low-bypass turbofan engines, then high-bypass turbofan engines.

Aircraft are categorized by noise into stages, from Stage 1 (loudest) to Stage 4 (quietest). In the regs, Part 36—Noise Standards: Aircraft Type and Airworthiness Certification—details exactly how each aircraft type’s noise levels are evaluated, using specified sensor positions, aircraft altitudes, environmental factors, and other particulars. Aircraft noise is measured in EPNdB, or Effective Perceived Noise in Decibels.

Older airliners like the 1960’s Boeing 727 were exceptionally noisy due to their low-bypass turbofan engines, and are rated as Stage 2 with a takeoff noise level of 102.4 EPNdB. In comparison, the Boeing 777-200—a 1990’s heavy airliner with massive twin high-bypass turbofans that have a diameter of a 727’s fuselage—is a Stage 3 at only 94.3 EPNdB. The 787-8, Boeing’s newest wide-body, is a Stage 4 at merely 82.6.

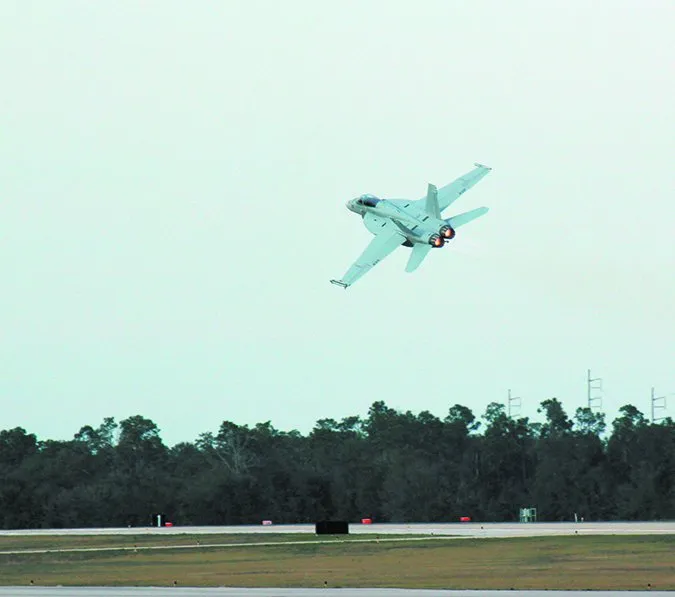

As older aircraft reach the end of their service lives, the FAA, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), and other aviation agencies worldwide continually tighten their noise restrictions. The 1990 Aircraft Noise and Capacity Act phased out all Stage 2 airliners in the USA by 1999. The FAA Modernization and Reform Act of 2012 banned all jets under 75,000 pounds that didn’t meet Stage 3 requirements—such as popular corporate models like the Gulfstream III and Falcon 20 (Its Coast Guard derivative, the retired HU-25 Guardian, is shown above.)—from flying in the continental United States starting on January 1st, 2016.

These noise bans can have far-reaching repercussions within the global airline industry. A 2002 European Union ban severely impacted Russian airlines by banning about two thirds of their fleets—mostly older Soviet-era models—from flying into Western Europe.

“Hush kits” are available that can modify some Stage 2 aircraft to Stage 3 requirements, but they’re pricey. Owners have to weigh their return on investment on old airframes.

Shut it Down

What happens when voluntary noise abatement procedures aren’t cutting it and late-night flights keep irritating folks? Can the airport authorities act like the police yanking the plug on a raucous house party by establishing a curfew? Well, sort of…

Before 1990, some airports had curfews. These included California’s John Wayne Airport (KSNA) and San Diego International Airport (KSAN). That year, however, the Airport Noise and Capacity Act (ANCA) went into effect, establishing a new national noise mitigation policy. Airports that already had curfews were allowed to keep them.

Since then, however, no airport has been allowed to establish a new curfew. ANCA ensures airports do not “impose an undue burden on interstate and foreign commerce.” A 2009 attempt by Burbank airport to create a curfew was shot down by the FAA under ANCA. Among the curfew’s opponents were FedEx, UPS, and other overnight cargo carriers.

For those that remain, the particulars of curfews vary from airport to airport, and may require some digging to find. An example? San Diego International Airport (KSAN) has no noise restrictions listed in the Chart Supplement page. However, on its official noise site, it clearly states that there are no departures permitted between 11:30 p.m. and 6:30 a.m. of any kind, barring emergency and air-ambulance flights. Arrivals are unrestricted.

So what happens if an aircraft busts those restrictions? San Diego hits them in the bank account. Between 2010 and 2015, KSAN had 217 curfew violations. Of those, 100 were dismissed because the aircraft was suffering from unavoidable mechanical issues. The other 117, though, amounted to $682,000 in fines.

Another major field with a noise curfew is New York’s LaGuardia Airport (KLGA). It shuts down from 12 a.m. to 6 a.m. between April 5th and December 31st. If your flight gets in late, you might have to divert to nearby Kennedy. Now, there is some wiggle room. If weather’s been playing havoc with the ATC system, they may keep the doors open late for the stragglers.

Wherever you fly, do your research and see what kind of noise abatement procedures might affect your flight. Don’t be that person who ruins somebody’s day. Be the neighbor who gives aviation a good name and helps strengthen its relationship with the non-flying public.

Tarrance Kramer likes to keep the peace while working traffic out in the Midwest.