You’re flying along, listening to a controller issue instructions to many aircraft. From one second to the next, you suddenly start hearing a different controller’s voice. You haven’t changed frequencies. They’re seemingly picking up where the first one left off.

Controllers are used to hearing voice changes from an aircraft. Many times a day, I’ll clear someone for takeoff, and one voice reads it back. Two minutes later, as they’re off the departure end, I’ll say, “Contact departure.” Now a different voice responds. We’re aware the flying vs. talking duties bounce between pilots in the same cockpit.

The difference is, though, when an aircraft’s “voice” changes, the non-talking pilot isn’t typically unplugging and stepping out the aircraft’s door. She’s still there in the cockpit, listening, and actively involved in the aircraft’s operation. Meanwhile, the previous controller could be down the street, grabbing a sandwich.

How do controllers ensure that all the information is passed between themselves, so the new controller can seamlessly continue working the traffic?

Getting Spooled Up

Pilots don’t typically blindly climb into their craft and fly away. There’s a preflight process. Controllers follow a similar path before plugging into a control position.

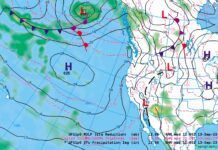

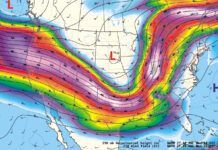

After clocking in for my shift, I head into the radar room, the nerve center of our facility. Computers sit squirreled away in a corner, where we pre-brief for the day. There’s a pre-recorded weather briefing from our overlying Center.

We must also complete electronic briefings on various subjects, like equipment changes, outage notices, and refresher briefings on our regulations. It’s akin to a pilot’s preflight brief: weather, equipment, NOTAMs, updated “company” procedures.

I’m also taking in the general energy of the radar room. Are the controllers relaxed, leaning back in their chairs, chatting idly between occasional transmissions? Or, are transmissions flying rapid-fire from controllers hunched over their scopes? Is the inbound arrival map lit up like a flaming Christmas tree, or are there only a few targets inbound?

Briefings complete, I report to the supervisor’s desk. The supervisor takes a look at who’s been “on position” the longest. “North sector’s up for a break.” I’ve got my assignment. Traffic awaits….

Soaking It In

“Transfer of Position Responsibility” is the official term for a controller relieving another controller. The roadmap for this is the Position Relief Briefing (PRB) checklist.

When you fly out of a towered airport, do you typically call up Ground and ask them, “Hey, can you read me the latest METAR, the active runway, the approach in use, NOTAMs, and wildlife advisories?” I’d hope not! There’s a thing called an ATIS that covers all of that.

A relief briefing starts out a bit like getting the ATIS, where I absorb information on my own. Beside each control position is an Information Display System (IDS) screen. Its sections include facility staffing and the Status Information Area (SIA). The latter’s content varies by location. Here beside a radar scope, the SIA displays the ATIS code, active runways, advertised approaches, weather, and NOTAMs for all airports in our airspace. A control tower’s display might only show information relevant to that airport.

For instance, I see our main airport’s ILS is out of service. That would appear on both the tower and radar SIA, since it impacts both operations. I also note our neighboring Center is using an unusual frequency. Our tower—fifty miles from that boundary—doesn’t care about that, so it won’t be on their SIA. On the flipside, my radar SIA wouldn’t show any local taxiway closures or mowing, since they only matter to Tower operations. The whole point is to present only information relevant to that position.

Along with external airport status, the IDS shows our current staffing. Which radar sectors are open? Which control tower positions are open? We’ll often have a list of buttons with each sector, with the radar sector’s identifier. For instance, N for North, S for South, and F for Final. If I see the N and S buttons are lit up green, and F is grayed out, that means North and South sectors are open, while Final is currently closed.

In your cockpit, after you’ve listened to ATIS, you would call Ground. “N123AB ready to taxi, with information Bravo.” That single word—Bravo—tells the controller you’ve got the latest info.

ATC uses a similar shorthand. Of our relief checklist’s five categories, labeled A through E, the SIA display and staffing configuration are items A and B. I plug my headset into the console. My friend, whom I’m relieving, presses the Relief Briefing (RB) button on our comms panel, initiating a recording of our briefing. At this point, I tell her, “I’ve got A and B.” Translation: I’ve previewed the SIA and staffing configuration, and I’m ready for a verbal briefing.

Storms and Students

Item C on the list—and the first required to be verbally briefed—is Current Weather. The initial computer forecast I received earlier painted a broad picture of mostly scattered clouds, with occasional showers. That isn’t necessarily reality. The controller getting relieved must tell me what the actual conditions are in their chunk of airspace, and how they’re impacting her traffic.

“Alright,” she says, “weather is VFR. Bases reported at 3300 feet. Get them below that, and visual approaches work great everywhere.” Good. That makes life easier for everybody.

She points to the northwest corner of her sector. There is a blob of precipitation there, on our boundary with Center. “Aircraft are deviating around this. Most want to go west. I’ve coordinated with Center. We’ll have control on all arrivals from there until 1300Z.”

I note the time. It’s 1220Z. For the next 40 minutes, Center is allowing us “control” in that location, to turn, descend, or climb any arrivals, as much as we want, before they enter our airspace. Normally, we only have limited control for turns before they cross the boundary.

“We’re also looking for PIREPs here and here.” She points to two satellite airports whose ceilings are below 5000. We’re required to solicit PIREPs when the ceiling and/or visibility are less than 5000 feet or five miles, respectively.

“Training.” That’s item D. She jabs a thumb to her right. “Training team on South.” I’d noticed a trainee plugged in with his instructor earlier, a new guy. His hunched, tense posture and death grip on his pen spoke volumes for his current mood.

“He’s been … doing okay. Watch out for late handoffs and late switches.” When we transfer control of an aircraft from one sector to another, it’s called a handoff. The aircraft’s current controller sets the aircraft’s target to flash on the receiving scope. The other controller clicks the target, stopping the flash and turning it white on their scope, thereby accepting the handoff. The first controller will shortly thereafter tell the aircraft to contact that new controller’s frequency.

Per her warning, the trainee hadn’t been that timely. Right on cue, the instructor rolls his chair over to us and points at a Piper Malibu about to bust our airspace, not flashing at us yet. “Point out. Watch this guy,” he says, frustrated. His trainee had forgotten to hand it off. The controller I’m relieving says, “Point out approved,” giving the training team consent to enter her airspace.

Who Goes Where

That trainee gaffe is the perfect segue into E, the checklist’s final section: Traffic. Since entering the building, all of the situational awareness I’ve acquired so far has been preparing me for this moment: taking responsibility for the aircraft in our airspace and the people aboard them.

“Okay, traffic.” She points at the Malibu the instructor indicated and says, loudly, “You heard that point out from South.” I’m clearly not her only audience. The trainee sits up, confusion on his face. Then, the realization hits. With a dejected sigh, he starts flashing the target to her. “I’ll take that handoff,” she says. Click. “Not talking to him yet, of course. Anyways….”

She points to a Cherokee on final at a satellite airport. “He’s doing an RNAV 8 approach with a published missed approach. He’s already on the tower.” She holds up a flight progress strip with the Cherokee’s callsign. “These are his next requests.” The strip has two RNAVs and a VOR approach to a full stop marked on it. The first RNAV has been checked off, as it’s the one he’s flying now.

There are three airliners inbound. She starts with the one closest to the airport, on a base leg for Runway 9. “This one’s down to 2000 on a 180 heading, speed 170 knots or greater, looking for the airport.” Two more are north of the airport. “He’s on a 270 heading, level at 3000, slowed to 210 knots. This one’s descending to 5000, heading 230. No speed restrictions given.”

As she’s telling me about the last one, the first airliner reports the field in sight. My friend says, without missing a beat, “Cleared visual approach. Maintain 170 knots or greater to a five mile final. Contact Tower.”

The traffic doesn’t just stop during a relief briefing. Controllers must be able to bounce back and forth between the briefing and working airplanes. “Okay, you heard that too,” she says. “Sure did,” I reply. She goes on to tell me about some routine overflights.

Then she points to a VFR Cessna. He’s got “SVY” written on his target. “This guy’s doing some aerial survey work at 1900 feet, running east-west lines at 1900. They start about here—” She points. “—and end about here.” The second spot is just inside our main airport’s airspace. “Tower has the point out.” Good, so our tower’s watching the Cessna whenever he comes close.

One Last Chance

Getting through a briefing sometimes takes a while. The more aircraft and the more weather, the more complex it can be. Interruptions can come from other controllers coordinating, aircraft checking in, aircraft that need clearances, and many other sources. The trick is to just stay the course and not lose your train of thought.

Thankfully, she’s not too busy. We’ve reached the briefing’s conclusion, checked all the items on the list. Now’s the time to tie up any loose ends.

At this point, many of us like to reiterate some of the key NOTAMs impacting our operation. Even though they’re on the SIA, a little verbal reinforcement doesn’t hurt. It’s all part of looking out for one another. I’ll do the same for my relief when the time comes. “I’m sure you saw it,” my friend says, “but our ILS is out. Also, we’re using 131.22 for Center’s Low sector. Any questions?”

Now’s my chance to clarify anything she’s told me about. I think she’s covered everything, so I say, “Nope. I’ve got it.” She stands and unplugs, and I slide into the chair.

Now everything on the scope is my responsibility. The Malibu from South checks in, and I issue him the altimeter. I turn the next airliner on a base leg. I issue traffic to the survey aircraft. Seamlessly, I pick up where she left off, and keep moving forward.

These briefings happen countless times daily in every ATC facility. While the voice pilots hear changes, underneath the transition between controllers is the same mission: keep the flow of traffic safe and organized.

Control Tower Considerations

A relief briefing in the control tower shares many aspects with a radar briefing, like staffing, weather, and aircraft traffic. Tower’s a different beast, though, and its Position Relief Briefing checklist reflects that.

For starters, a tower’s traffic briefing item isn’t limited to just airplanes. Airports are alive with vehicle traffic as well. Maintenance trucks flit about, fixing lights and patching concrete. Mowers keep the grass trimmed. Winter months up north mean fleets of snow plows scraping the runways clean. The new controller needs to know about all of them.

Taxiway or runway closures can seriously impact operations, turning a smooth in-and-out flow from ramps into a slog. When they’re in effect, the relieved controller will often give guidance on how to adapt, “Taxiways A and H are closed. I’ve been using Zulu and Tango to go into the ramp, and Whiskey to exit.”

Towers are also on the front lines of flow-control programs, handling aircraft impacted by call-for-releases, expect-departure-clearance times (EDCT), or ground stops to airports nationwide. “American 123 is holding on Yankee, waiting his release time to Dallas at 1430Z. Alaska 456 knows about his EDCT time to Seattle. LAX is in a ground stop, with an update at 1500Z.”

While we’re talking about an area only a few miles wide, versus the massive airspace worked by approach controls and centers, a tower’s surface conditions, flow control, and traffic load can turn it into a complex, challenging operation.

Tarrance Kramer likes to keep his briefings quick and to the point while working traffic in the Midwest.