That typical one-hour fuel reserve most of us use for personal flying works great, mainly ’cause we rarely need it. In most cases, there’s four-plus hours of fuel for a two-hour flight that includes an alternate just down the road. Use a (conservative) default fuel burn to estimate it, and you’re all set. But when loaded up to max weight for a long trip requiring IFR contingency planning, fuel can get tight. That’s when we’ll just stick a suitable fuel stop in the flight plan and go, right? Sure, unless the thought of making it non-stop can trigger symptoms of get-there-itis.

Perhaps you feel a fuel planning exercise coming on. If you do, you’d be correct, but stick with this—it’ll be interesting. Let’s start with the route: Rochester, New York, to Indianapolis Metropolitan.

Need More Gas

The destination, KUMP, is just outside the big Indianapolis airport and is closest to the family gathering where you’ll spend a short holiday break. All four seats and the baggage compartment of the Cessna 177RG are filled, leaving you with something less than the five hours’ endurance you’ve grown accustomed to when out fun flying with one or two of the kids. To find out how far you’ll get, start punching in the aircraft performance from the POH and load weather into your preferred app.

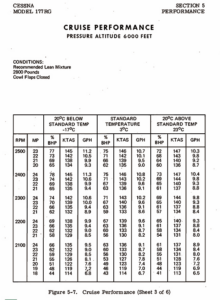

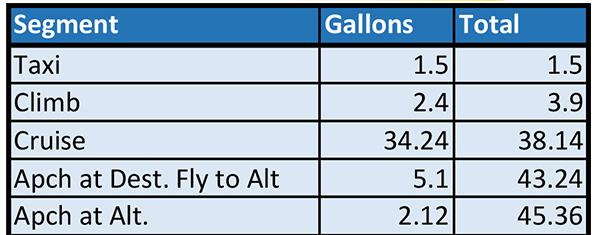

It’s 421 NM RNAV direct from Rochester to Indie Metro. At a default true airspeed of 140 knots at 6000 feet, the app forecasts a flight time of 3.2 hours at 131 knots groundspeed. You want to use the max-speed cruise setting, which burns 10.7 gph for a total of 34.24 gallons. Best to add, per the POH, 1.5 gallons for taxi and 2.4 gallons to climb to 6000 feet pressure altitude, for a running total of 38.14 gallons.

It’s 421 NM RNAV direct from Rochester to Indie Metro. At a default true airspeed of 140 knots at 6000 feet, the app forecasts a flight time of 3.2 hours at 131 knots groundspeed. You want to use the max-speed cruise setting, which burns 10.7 gph for a total of 34.24 gallons. Best to add, per the POH, 1.5 gallons for taxi and 2.4 gallons to climb to 6000 feet pressure altitude, for a running total of 38.14 gallons.

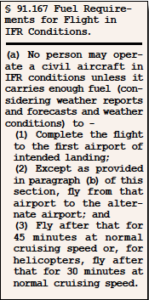

Next, run the weight and balance for a maximum gross weight of 2800 pounds, 1093 useful load. The Cardinal’s tanks hold 60 gallons, but payload only leaves 49 gallons. The flight would leave about 10 gallons remaining, a solid hour reserve. But you’ve yet to work in IFR weather and regs, starting with the ubiquitous legal minimum reserve in §91.167, calling for 45 minutes beyond the destination and alternate.

Speaking of which, you will need one. Weather’s CAVU at Rochester and remains so for nearly half the flight, then ceilings and visibility dip down to medium-low IFR. The only suitable approach at Indie Metro is the RNAV 33 with LNAV mins of 1260-1. You’ll need it as the latest forecast is for 500-1. Most of the area’s socked in with even lower conditions: Indianapolis International is at 300-1/2 and one of the satellite fields, Eagle Creek to the north, is 400-1.

That means looking further out for an alternate to meet §91.169, which requires alternates for non-precision approaches to have mins of 800-2 by arrival time. Wading through a sea of pink LIFR dots on the EFB, you see that to the north, KOKK (Kokomo, Indiana) is up to 800-2—not ideal, but it qualifies. The LNAV 32 approach there also goes to 1260-1 and the ILS 23 allows for much lower, just in case. KOKK requires local weather, but has no other limitations that apply to you. Kokomo is 35.5 NM north of Indie Metro, about 15 minutes’ flight time.

Now total up the fuel burn. You save fuel on descent and while slowing for an approach, it will also take an estimated 10 minutes to fly the approach at KUMP, so estimate additional fuel burn of 8.5 gph, for 5.1 gallons consumed to fly the approach at KUMP then get to KOKK. Add that to the departure-climb-cruise fuel (38.14) and it’s now up to 43.24 gallons. With 49 gallons available, that leaves 5.76 gallons, or roughly 35 minutes remaining. Now add in 15 minutes to fly the approach at KOKK (staying slower at 8.5 gph) and it’s up to 2.12 more gallons, which would leave you with nearly empty tanks and a lot of stress. You’re thinking it’d never come to that if weather remains the same and you set up properly for an awesomely executed approach at Indie Metro. But to meet §91.167, “IFR fuel requirements,” the calculations show you want 7.8 gallons as a 45-minute reserve beyond the alternate. Can you massage the plan to make it legal?

Regs vs. Real

For starters, were you really over the limits of §91.167? This is where we easily fall into the regulatory trap because we tend to picture a flight to an alternate like this: Fly an approach at the destination, go missed, get a clearance to proceed to the alternate, and then land with 45 minutes of fuel remaining. But the rule is designed to pad that a bit more, requiring “enough fuel (considering weather reports and forecasts and weather conditions) to complete the flight” at the destination, then fly to the alternate, then “after that for 45 minutes at normal cruising speed…”

FAA letters of interpretation addressed the inevitable questions to clarify this. In a 2006 inquiry, (the second by this inquirer) the FAA in its reply states the rule “assumes the pilot will attempt to land at the destination airport and then fly to the alternate … This reasonable scenario includes an approach at both the destination airport and at the flight’s final landing at the alternate.”

So you do need that approach fuel at KUMP, then fuel to land at the alternate using the expected approach. For your plan, you need more fuel. Maybe tweak the cruise and try 8000 feet? That alone doesn’t gain much: TAS, 147 knots and 10.4 gph, and just a couple of minutes faster groundspeed. Flying at lower power settings, say 20 inches MP, results in 9.2 gph and 3.3 hours flight time between KROC and KUMP. Add taxi and takeoff fuel and that’s 34.53 gallons plus 5.1 for the approach for 39.63 gallons—just to make it to the destination. Add in 1.2 gallons for a short climb back to 3000 feet, 5.1 gallons for the flight and approach to the alternate for a grand total of 45.93—still neither legal nor assuring.

While not further defined in the reg, there is an FAA letter of interpretation (2009) indicating you must use “normal” along with “accurate and verifiable” cruise settings for purposes of fuel planning for §91.167. Using a low-power cruise setting just to get a number you want might push your use of “normal” into a grey zone.

Not only that, what good is a legal plan if it doesn’t leave room for other extras you might need, like two attempts at the destination? What about a traffic delay at the airport resulting in a hold, which could eat up a few more gallons? If you plan for one approach with one missed and an immediate diversion to the alternate, plus vectors from ATC, that’s reasonable. But it doesn’t account for something you might actually want to do, or for abnormal operations like a lost-com situation, in which a missed approach might require yet more fuel to sort things out.

A Better Option

In the end, the simpler and safer plan is also more convenient. How about just committing to one approach at KUMP, and if need be, fly back to the northeast towards VFR conditions at KAXV Neil Armstrong Airport in Wapakoneta, Ohio. This leg will take just 0.6 hours and 5.5 gallons direct, with no approach needed and you can even cancel IFR in the air when it’s suitable.

In the end, the simpler and safer plan is also more convenient. How about just committing to one approach at KUMP, and if need be, fly back to the northeast towards VFR conditions at KAXV Neil Armstrong Airport in Wapakoneta, Ohio. This leg will take just 0.6 hours and 5.5 gallons direct, with no approach needed and you can even cancel IFR in the air when it’s suitable.

The best thing about this is that KAXV will also serve as a contingency fuel stop on the way to Indiana. After all, you’ll monitor the actual speed, winds, fuel burn and flight time continually and decide en route if you want to land there. More importantly, you’ve scoped out a good restroom stop in the event someone needs it—an added stressor when searching for a diversion airport in low weather. Always going with the plan that leaves more than minimum fuel to spare is a good way to start the instrument-flying season.

Elaine Kauh is a CFII in eastern Wisconsin. She recommends adding five pounds extra (or more) per pilot and passenger when calculating weight and balance in November and December.

Great article, thanks Elaine!

I would never get to the point where I calculate .1 or .2 gallons for anything

89+859+89+