Whether it’s a result of faulty instruction or an accumulation of bad habits over time, I often see pilots who come in for a Flight Review or Instrument Proficiency Check who exhibit habits that either make no sense or worse yet, contribute to poor piloting technique. Being able to recognize these mistakes and correct them is often difficult especially without someone looking over your shoulder. Sometimes critical thinking after a flight is the best way to figure out if what you did was correct. Take that time and look for improvements from each and every flight.

Uh, What Happened?

One of the most common problems that I see is timing an ILS approach. When I ask why the pilot timed the approach, the standard answer is, “So that if the glideslope fails, I can change over to a localizer approach.” That reasoning is common and has even been promoted in these pages.

But let’s stop for a moment and think about this. First, consider whether you have actually briefed both the ILS version and the localizer version of the approach. If you haven’t briefed the localizer version, is it really a good idea to continue an approach with which you are unfamiliar? It’s certainly not a good idea to brief an approach while you are in the middle of it.

Next, if the glideslope failed while you were already on the approach, do you know why it failed? Is it a problem with the equipment in your plane or is it a problem with the ground equipment? Whatever caused the glideslope to fail, could be likely to cause the localizer to fail soon. Or perhaps you did something so you don’t even know if your equipment is working correctly.

Without answers to these questions do you really want to continue the approach? The smarter play is to immediately execute a missed approach, get to a safe place, figure out what happened and then decide the best course of action. Don’t try to figure out problems when you are close to the ground and in the clouds.

Timed Approach—Last Choice

Another “error” that I see on IPC’s is choosing a timed approach at all. Yes, they are certainly legal. Occasionally they are the only approach for a given airport, so you have no choice. But unless you can accurately determine your ground speed (timed approaches are based on ground speed, not airspeed), then your estimate of the missed approach point could be way off.

Even if you do accurately know your ground speed, how well are you able to maintain that speed with shifting winds close to the ground and all the other tasks demanding attention on an approach?

These days there are really only two ways to determine ground speed—DME and GPS. Generally speaking, if you have either of those to help determine ground speed, then you will not need to use timing to determine the missed approach point (MAP). I typically tell folks that unless it’s an emergency you should not execute an approach in IMC that requires timing if the ceiling is anywhere near minimums. If timing is really going to be needed and the ceilings are near minimums, go somewhere else.

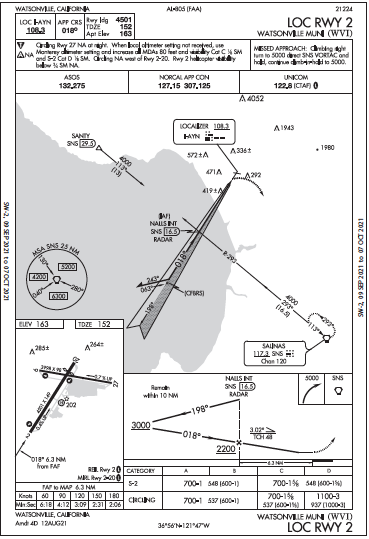

Consider the Watsonville LOC RWY 2 approach. NALLS is easy to identify and the MAP is 6.3 NM later. But there’s no DME source to determine the MAP, so the only way shown to identify the MAP is timing. Note the mountains north of the airport that demand good timing. (Whether you can legally use GPS is a separate discussion, but I’d use GPS at least as a backup.)

Know What’s Required, or Not

Interpreting the “1-2-3” rule to know when it’s okay not to file an alternate is another common error. The details are contained in §91.169. If the weather at your primary destination has a forecast ceiling of at least 2000 feet and three statue miles visibility for one hour before and one hour after your proposed arrival time, then you need not file an alternate.

But what most folks fail to realize is that the 1-2-3 rule only applies if your primary destination has an instrument approach. Yes, it is legal, and maybe even common, to file an IFR flight plan to an airport that doesn’t have an approach. If your primary destination doesn’t have an instrument approach then you are never excused from the requirement to file an alternate.

The other common misinterpretation of this rule arises when the forecast contains a probability of low ceilings or visibility. For example, assume the overriding forecast says that ceilings will be 10,000 feet and visibilities will be 10 miles, but there is a 20-percent chance of ceilings below 2000 feet or visibility under three miles. Simply put, §91.169 does not allow for probabilities. So even if there is a small chance of low ceilings or visibilities then you can’t skip the alternate.

Some say that the smart move is to always file an alternate. You never know if the weather man will get it right. You certainly don’t want to need an alternate and not have prepared one to possibly use.

Slaves to Magenta

Many instructors tell students to precisely follow what the GPS says to do throughout a procedure. In particular they insist that when a GPS says it’s time to begin the course reversal, the student must start the turn immediately. That’s not only legally incorrect, sometimes it will be the wrong thing to do.

AIM section 5-4-9 says that procedure turns do not need to be done precisely as depicted on the chart. The exact time to initiate the course reversal and headings to be flown are up to the pilot so long as you stay on the protected side of the turn and within the stated distance. The GPS in your plane however might also be installed in a jet flying much higher speeds. At those speeds, course reversals need to be initiated much sooner, often as soon as permitted.

But in your BugSmasher 1200, flying the approach as a Category A aircraft, it pays to wait a bit to begin the course reversal. In most cases, the chart will tell you that you must complete the course reversal within 10 miles of beginning the outbound segment. Using DME, GPS, or simple timing, you should wait until you are at least a few miles beyond the fix.

The advantage here is that waiting until you are further out gives you more time to capture and track the course inbound. If the fix is a VOR, the needle will be much less sensitive when you are further away. This makes everything easier. As any pilot who has transitioned to a faster aircraft will tell you, additional time on an approach makes everything easier and less prone to error.

Whether it’s a result of faulty instruction or an accumulation of bad habits over time, I often see pilots who come in for a Flight Review or Instrument Proficiency Check who exhibit habits that either make no sense or worse yet, contribute to poor piloting technique. Being able to recognize these mistakes and correct them is often difficult especially without someone looking over your shoulder. Sometimes critical thinking after a flight is the best way to figure out if what you did was correct. Take that time and look for improvements from each and every flight.

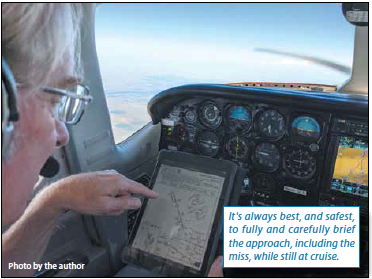

Prepare to Miss

Are you ready for the missed approach? Many pilots don’t bother to brief the missed. They hear the weather report and assume they’ll be able to make the landing. But when the weather is changing and things turn out worse than expected, a missed approach can surprise the unsuspecting pilot.

I had an IPC client who, when asked to execute a missed approach, replied, “What’s that?” He had gotten his instrument rating and never flown a missed approach. He had no idea that the missed approach existed. I guess he just assumed every approach would terminate with a successful landing. (ATC: “How will this approach terminate?” Pilot: “Well, successfully, I hope.”)

When most pilots brief the missed approach, it’s often very “brief.” Missed approaches really need to be thought through. At least the first two steps of the missed need to be memorized. Once the missed is begun, there is no super rush. As the great college basketball coach, John Wooden, once said, “Be quick, but don’t hurry.”

Get the plane headed upwards and stable. After the climb has begun, you can refer to the hieroglyphics on the approach chart to remember what needs to be done. I’ve heard the “5 Cs” of the missed approach as a good memory aid—Cram (all levers forward), Climb (pitch up to approximately 8 degrees), Clean (flaps and gear retracted), Cool (open the cowl flaps) and finally, Course (turn the correct direction). Throw in an extra “C” for Communicate, once everything else has been done. Whatever method you use, just be deliberate and smooth in the actions that you take. There’s no need to rush but you can’t be leisurely about it.

When I ask pilots how low they can go on an approach, the common reply is to look at the minimums on the chart and pick out the answer. But what if the runway has working approach lights? You can use the approach lights to go below minimums. But how much lower can you go?

Frequently I hear pilots say you can go another 100 feet lower before you have to see the runway environment. A close reading of §91.175 (c)(3)(i) shows that the correct answer is that you can descend all the way to 100 feet above the touchdown zone elevation, not just another 100 feet. While descending using just the approach lights, particularly if the approach lights have a rabbit, can be done safely by a proficient pilot, it’s not the stuff that a Saturday afternoon flier should attempt after a five month lapse in instrument currency. Be sure to continue following whatever navigation guidance you have.

One-Trick Pony

While it’s not a “mistake” in the sense of being wrong, I do see a lot of pilots who fly GPS approaches exclusively. There’s nothing wrong with GPS approaches. In fact, most of the time they’re easier. But nothing in this world is guaranteed. There’s always a chance that something could disable your GPS.

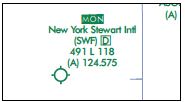

Although many VORs are being decommissioned as we transition to the MON (minimum operating network of VOR’s) there will still be many VORs left in operation even 10 years from now. You need to be able to fly a VOR or ILS approach as well as you can fly a GPS approach. Even if you never fly a terrestrial approach while in IMC, practicing them will help sharpen your general instrument skills and prepare you for the day you hope will never come when the weather is down, you’re low on fuel, have to land, and GPS is unavailable.

As an instrument pilot, we should always be striving for flights where we make no mistakes. When you realize you’ve made a mistake, make a mental note to not repeat the error.

But even more difficult is finding the errors that we don’t even know we’ve committed. Flying with an instructor is the best way to root out these mistakes. But if you fly with the same instructor all the time, he or she might not notice mistakes that you consistently make. This is especially true if the mistake is one taught to you by the very same instructor. The best solution is to fly with a different experienced instructor from time to time and see what you can learn.

Great read, I like the “Question authority” part a lot.