The Lear 35 medical-transport flight on which I was the captain had just departed Tampa International (KTPA) for Portland, ME (KPWM) carrying an elderly patient and his wife. It was a busy departure as we were already looking for deviations around the typical Florida summertime thunderstorms. The “pop”—accompanied by the sound of rushing air—came just as we passed through 12,500 feet.

As pressurization problems go, it could have been far worse, especially if we had already reached the Lear’s lofty cruising altitude. Still, this particular scenario created plenty of opportunities to practice our threat and error management (TEM) techniques.

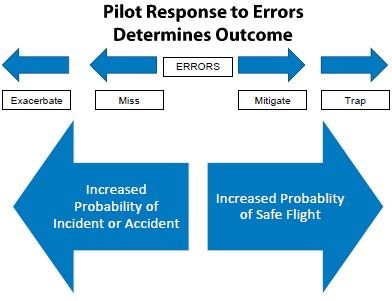

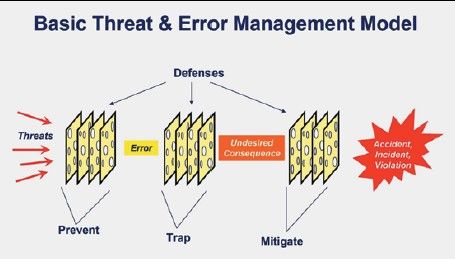

If you’re not familiar with TEM, here’s the scoop. TEM starts with reality: when error-prone humans operate in a threat-rich environment, stuff happens. So, TEM teaches pilots to recognize threats, reduce errors, and manage to prevent what the discipline politely calls an “undesired aircraft state.” Another core concept is breaking the

threat-and-error chain at the earliest point. Because TEM is as thoroughly embedded in my engrams as any other part of my training, it was only after landing that I could truly appreciate how well it served me, my crew, and our passengers in this real-life event. It can serve you as well, regardless of what you fly.

Threats Come At You

TEM defines a threat as an event or situation that comes at you. You can’t influence or control a threat, but it increases operational complexity and requires attention and proper management. In TEM, the definition of threats is a bit like the menu at Starbucks. There are some basic categories, but the subcategories offer a depth of descriptive possibilities.

On that particular day, the universe served up two of the three basic categories. We had an operational threat in the form of the equipment malfunction. We had an environmental threat arising from the sultry summer weather and from the congested airspace. We had to avoid letting these issues create a mismanaged threat, which involves pilot error—which we’ll get back to. Our operational and environmental threats were observable (versus latent). While the growing thunderstorms were expected, the malfunction we experienced was decidedly not expected.

Here’s how we handled the observable and unexpected operational threats that came at us. Moments after the noises, hot engine bleed air started filling the cabin. That’s consistent with the Lear’s emergency pressurization system. It is supposed to function when the emergency system is activated or, on some models, at a cabin pressure greater than 9500 feet. A quick glance at the cabin controller indicated that we were just slightly above sea level in the cabin, and we had not manually activated

the system. So, we didn’t have an actual loss of pressurization, but we did have an uncommanded activation of the emergency system. Our medical crew reported that the cabin temperature was 100 degrees F and increasing, endangering the patient and passenger.

Our trusty Quick Reference Handbook (QRH) didn’t have a procedure for this, so solid systems knowledge was key. The obvious solution was to turn off the bleed air. We did. It didn’t solve the problem. My next step was to reduce thrust to decrease the engine bleed air to the cabin. Then we declared an emergency and said we were returning to KTPA. The emergency gave us priority handling and authority to maneuver as needed around the building storms. We landed safely and got our patient and passenger out of the sauna-like cabin conditions.

The previous day took us into KTPA. We initially f lew into St. Pete-Clearwater, FL (KPIE) with a patient on board. The best (and longest) runway was closed, so we had to use a crosswind runway. We got the KPWM assignment while we were at dinner. Like most “will-fly-for-food” pilots, we immediately envisioned the lobster dinner we planned to enjoy in Maine’s cooler climate.

Being the PIC, though, I also needed to ponder possible environmental threats to the flight. The fuel required for the run to KPWM would put us close to maximum takeoff weight. After checking performance data, the FO and I concluded that a KPIE departure on the available runway would “probably” work, but offered little margin for any increase in aircraft weight or temperature. Having learned that “probably” in flight planning means that you must

rethink the plan, we decided to change our departure airport to Tampa International (KTPA). The new plan would have us reposition from KPIE to KTPA while the medical crew retrieved our passengers. Easy-peasy, right?

Not so much. Short flights in a fast airplane can be … challenging, especially when conducted during KTPA’s morning rush hour. With time pressure to collect our passengers, a 25-mile final, and the need for pre-departure refueling, there was plenty of opportunity to grapple with the environmental threat of congestion and dodge the potential for mismanaged threats from errors that could arise from the other issues. We got it all done with a few minutes to spare. You already know what happened next.

Errors Come From You

Now let’s talk about errors. TEM terminology holds that an error is a pilot action or inaction that leads to a deviation from intentions or expectations, reduces safety margins, and increases the probability of adverse operational events. Like threats, errors come in three categories: aircraft handling errors (speed, configuration, automation); procedural errors (intentional or unintentional deviation from regulations or limitations); and communication errors (misunderstanding between you and ATC). Errors do not always arise from threats. For example, selecting flaps above published flap operating speed might not be associated with any existing threat.

In the KTPA event, the pressurization system malfunction operational threat would have fallen into the aircraft handling error category if we had triggered the emergency system. We didn’t. But, this episode did involve an intentional procedural error. Remember that we’d be near maximum-takeoff weight with fuel for the expected KTPA-KPWM route? Since our threat occurred in our initial climb, we hadn’t burned much fuel and our return to KTPA would involve an overweight landing.

Could we have dumped fuel? Yes, but even if we did we’d still be somewhat overweight. Also, it would have meant more time in the congested and bumpy Florida air with a malfunction of unknown cause and extent. More critically, our elderly passengers were already baking in the back. I didn’t ponder long before opting to go straight in.

We had declared an emergency, and I had no qualms about using every bit of the authority it offers. I can honestly say it was one of the best and smoothest

touchdowns I’ve ever made in the Lear. Did I get any post-incident follow-up queries from ATC? No. Did I have to explain later to my boss? Yes. He wasn’t thrilled about the inspection the overweight landing required, but he would have been far less thrilled if undue delay had caused greater harm to the passengers, or to those on the ground affected by a low-altitude dump of Jet-A. Being PIC means making decisions. If I had a do-over, I wouldn’t change what I did.

Managing Threats and Errors

Threats and the errors that can arise from them increase the complexity of a flight. Managing them requires time and/or action, increasing workload, which itself is a threat. It follows that the sooner we manage threats or errors and break the chain, the more effectively we maintain safety.

In the language of TEM, we talk about trapping errors. A trapped error is the first step in breaking the chain of events that may lead to trouble. Here’s an example: ATC clears you to a new altitude while you are listening to ATIS. You are not certain you heard the assigned altitude. You set the altitude you thought you heard, but your inner voice tells you to request clarification before you climb. ATC confirms the altitude… and you learn that you misheard it. You just trapped an error.

A threat is an event or situation that occurs outside of our ability to influence (we cannot control the weather), increases the operational complexity of a flight, and requires our attention and management to maintain safety margins. Examples include dealing with adverse weather, high terrain, congested airspace, aircraft malfunctions, and errors committed by other people outside of the cockpit, such as air traffic controllers, maintenance workers, or fuelers.

Threats come in three categories: operational threats (e.g., equipment malfunctions or taxiway closures); environmental threats (e.g., weather and ATC); and mismanaged threats (threats that are the linked to or induce a pilot error). Threats are further classified into observable, such as weather, and latent, such as an equipment design issue or perhaps a cultural issue at a flight school that pressures instructors to sign off students. Additionally, threats can be expected or unexpected. In my flight from Tampa, the threat of runway length at KPIE was expected, observable, and mitigated by selecting another departure airport. The malfunction we experienced was not expected, but definitely observable.

It’s important to know that threats can also arise from the decisions we make. The all-too-familiar visual meteorological conditions (VMC) into instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) scenario is just one example.

Unexpected threats, such as malfunctions, often have to be resolved under some time pressure. It’s been my experience that decisions made under time pressure are often not the best decisions.

An error is a pilot action or inaction that leads to a deviation from intentions or expectations, reduces safety margins, and increases the probability of adverse operational events. Like threats, errors come in three categories: aircraft handling errors (e.g., speed, configuration, or automation); procedural errors (e.g., intentional or unintentional deviation from regulations or aircraft operating limitations); and communication errors (e.g., misunderstanding between you and ATC). Errors do not always arise from threats. For example, selecting flaps above published flap operating speed is an error that may not be associated with any threat.

You might wonder how CRM plays with TEM. Here’s the distinction: CRM is about managing resources, and TEM is about managing threats. Resources range from those that are obvious, such as another pilot flying with you, ATC, and Flight Service. Other resources are the technology we have on board such as ADS-B and our flight planning apps. —PP

An un-trapped error is just that: You make an error that you fail to recognize. Un-trapped errors might have associated safety consequences. For example, suppose you are flying an instrument approach and you do not set or anticipate the missed approach altitude. If you land, there is no safety consequence. But if you miss the approach and fail to climb to the appropriate altitude, there’s an obvious safety problem.

Failing to manage threats or trap errors often leads to an “undesired aircraft state,” which merely says that your aircraft is now in a position, speed, altitude, or configuration that reduces safety. It can result from something as simple as being 10 degrees off from your assigned heading or, more seriously, crossing a hold short line without a clearance. The ultimate undesired aircraft state, of course, is an accident.

So, trapping errors is key to managing threats and errors and thus avoiding unwanted consequences. It sounds simple, but isn’t. We humans often fail to recognize our errors or the errors of others, and we don’t always see threats before they become a real problem. Fortunately, we are also the solution. Through training and practicing TEM techniques, we can adopt strategies and countermeasures to effectively mitigate risks.

TEM starts with anticipation—recognizing that something is likely to go wrong, even if we don’t know exactly what or when. Anticipation leads to vigilance— always being on guard, even in routine situations. The next step is recognizing a problem. After recognition comes recovery, correcting the threat before it becomes an error or undesired aircraft state.

Recognition and recovery are both countermeasures. There are many other countermeasures we can use to prevent threats from turning into errors. Technology like flight planning tools, GPS, and ADS-B can help provide increased situational awareness and information both before and after departure. But note that technology can be a threat if it is a distraction. Don’t forget to look outside and know your equipment well. Proper pre-flight planning requires getting a weather briefing from a qualified briefer or from flight planning programs. Checklists and procedures that you consistently follow are also safeguards. Creating and following standard operating procedures used on every flight will help you become a more reliable pilot, especially if you are tired, distracted, or dealing with unexpected weather or a mechanical issue. As PIC, you are the last line of defense. As final authority, it is your responsibility to mitigate risk and manage safety. You trust your mechanic, but it is up to you to thoroughly preflight your aircraft. You trust the fueler, but it is up to you to verify the tanks are full.

I have previously defined a good pilot as one who demonstrates mastery of the aircraft and mastery of the situation. Using the TEM model is a proven strategy to improve your situational awareness, increase safety, and make you a more proficient pilot.

This was fantastic! Thank you so much!

Thanks Paul. Very insightful, and practical!

Excellent exposition on an important subject. When we read of an “incident,” everyone of us mentally makes the correct decision. Easy to do when employing hindsight sitting in our living room and reading about it – especially when we already know of the outcome. Not so easy when it is being experienced in real time. Having and, more important, utilizing a formalized organized system of steps to analyze, evaluate and decide is critical. Just as repeated use of GUMPS on landing, a mnemonic for the unexpected will mitigate the “pucker factor” and could pave the way for a better outcome. Of course, in the case of sudden catastrophic engine failure, my overarching precept in decision making is the mantra “When the engine stops, title to the plane transfers to the insurance company.”