Remember when you first picked up the mic in an airplane, either to ATC or at a non-towered field? Most of us were probably as tentative as a boy trying to get his first date . Even if you’re good at public speaking, few of us gain the comfort without first practicing with prepared remarks. But, on the radio our scripts are too vague and variable; we have to learn along the way. Meanwhile we’re so worried about sounding bad or saying the wrong thing, we often sound bad and say the wrong thing. Fortunately, practice makes perfect—or at least better.

While the objectives of pilots and controllers overlap, their needs and processes don’t. What do pilots need? Aviate, navigate, and communicate, in that order, right? In contrast, nothing in ATC starts without communication, which leads to us navigating pilots accordingly, while the pilot aviates. Pilots might not even have a need for ATC. A perfect example would be a non-towered field out in the middle of nowhere. However, in the world where most of us operate, we’re regularly talking to ATC.

It’s usually just a matter of time to become confident and proficient on the radio. I’ve found that most students who learn near Class Bravo airspace pick it up faster than those who operate solely out of non-towered fields. I also have friends in Alaska who rarely talk to ATC at all due to the nature of their mission, but even in situations like these, there are a few ways to keep your skills up.

Think First

Being good on the radio starts with effective communication as an individual. Can you talk to someone and carry on a conversation without blanking out? Of course you can; you’ve been doing it your whole life. But pilot communication is different—it has its own vocabulary, objectives, and techniques. We learn basic communications in flight training and continue learning as we grow as a pilot.

One of the biggest barriers I regularly encounter—and I’ve seen this become a safety issue far too often—is with pilots, usually students, who are not comfortable speaking English. Right or wrong, the official and universal language of air traffic control is English. That’s why being “proficient in English” is a requirement to be a pilot (or a controller, in most countries). Unfortunately, “proficient in English” is the only requirement and has no criteria. I’ve personally had a full traffic pattern and litterally half the pilots didn’t understand my instructions. (Lesson for us native English speakers: Listen and speak carefully and deliberately in a foreign country.)

Regardless of your English proficiency, to improve your in-flight communications start with the Pilot/Controller Glossary at the back of the AIM. Yes, it’s nearly 120 pages—you don’t need to memorize everything—but you should study it sufficiently that you’re familiar with what’s being said on the radio. This will tremendously help ATC help you.

Another way a pilot can better work with ATC is knowing how to respond to a controller’s communications. I will often point out traffic to a pilot who then mistakenly thinks that’s who they are following. The Pilot/Controller Glossary defines what is “traffic” and tells ATC how to issue it while telling pilots what to expect when they hear the word “traffic.” It’s almost a command word in that you hear traffic and immediately start looking out the window to search. If ATC adds the words “ALERT” after “traffic,” that means you’re too close to someone/something, so all eyes outside!

Another big one that I like to cite in the glossary is, “Cleared for the Option.” I’ve had pilots, even CFIs ask on frequency, “What exactly is the option?” I’ve even had pilots taxi around the airfield because they thought “Cleared for the Option” meant they could do anything they wanted. With this mindset, two runway incursions almost happened on my watch. “Cleared for the Option” is awesome in that “It is normally used in training so that an instructor can evaluate a student’s performance under changing situations.”

Don’t forget that no matter what your clearance, you can always go around. Say you’ve been cleared for a full-stop landing. That’s what the controller is expecting. So, if you land, stop. Even still, if you don’t like things on short final, go around. As always, though, inform ATC immediately when you deviate from your clearance. For example, sometimes I’ll have six or more playing in the pattern. Everybody is getting touch and goes to keep things moving. If one guy stops, or takes too long to go, it messes things up. That should be requested, or at least announced if unexpected.

Pattern Drill

Beyond the book knowledge is simply practical knowledge and experience. Have thorough discussions with your CFI about the phraseology you’re learning. Then apply that knowledge on your upcoming flight.

Say you’re on a BFR, returning to the pattern for some landings. But your CFI has a couple other things in mind and tells you to ask for a “Pattern Drill.” You have no idea what that means.

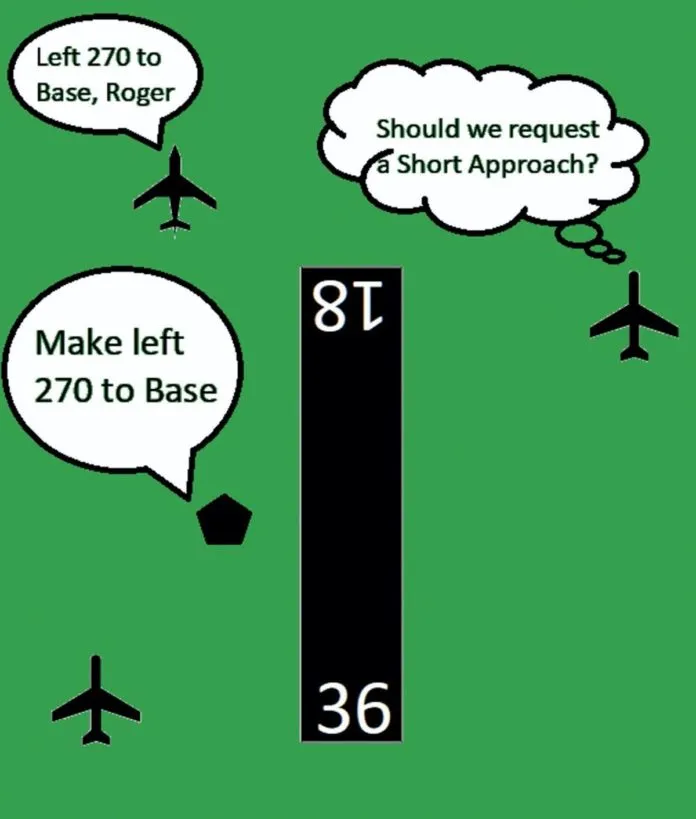

At some Class D airports, the Tower has developed a procedure that is given to flight schools to allow a series of maneuvers like a 360 on downwind, a 270 to base, a short approach, a go around, and a few other surprises. The CFI knows what’s up, but these might be unknown to the pilot. They allow the CFI to watch the pilot react to surprise instructions, and get more comfortable with the radio.

When a CFI requests a pattern drill, traffic permitting, the tower controller will issue these instructions, quite literally out of no-where. My personal favorite is the “GO AROUND!” I personally won’t send anyone around past the threshold without a legitimate safety issue, but, before then the drill helps pilots stay flexible, alert, and get more comfortable on the radio.

Your local Class D might not have a booklet ready to go, but some of the controllers might be familiar with a pattern drill and would provide it if requested.

More Steps

Reading a script can only do so much for you, regardless of the kind of learner you are. Procedures are great, but in the real world, a few words create a more organic connection between a pilot and the controller. Thanks to technology, you can even experience this after the fact, using sites likeliveatc.net. where you can listen to ATC frequencies over the Internet.

Put yourself in that pilots’ seat and imagine how you would respond to the controller’s instructions. It doesn’t have to be the correct response, but a response is a good place to start. If you read this and say to yourself, “yea I feel I’m pretty much good to go,” then great.

You shouldn’t forget that we’re always learning. If you’ve got the “communicate” part down pretty well, why not help someone who doesn’t? You needn’t be a CFI to mentor others on radio communications. Once one starts to get the hang of things, they will be able to anticipate ATC. But be sure this habit doesn’t turn into expectation bias, like expecting “taxi to parking,” but getting, “turn left contact Ground,” to which you respond, “Taxi to parking, thanks.” I hear this one pretty often believe it or not, and one of the only things I combat it with is a stern, “Negative, contact ground.” Keep ATC communication in your priorities while you try to stay ahead of the airplane.

Frequency Change Approved

From an operational standpoint, I’m a “Phraseologist.” My existence at 100 feet AGL is based on the words and phrases I can say to move Plane A from HEERE to THERE without hitting Plane B and while following Plane C. Before radios Archie League used a checkered flag (GO), and a red flag (STOP). Now we have “Climb via the SID,” and “RNAV to (waypoint), cleared for Takeoff.” ATC is constantly changing to meet the needs of today, and will do the same tomorrow. There is a reason that the ATC system in the U.S. is one of the safest in the world, and it all boils down to communications and established procedures.

If the radio confidence of a pilot needs improvement, after recognizing it and seeking to get better, there are plenty of routes the pilot can take. I always encourage a tour of your local ATC facility, talking to the controllers in person (helps ease the apprehension that we are mean), and asking questions. And always keep in mind, that you can and should ask, in plain language if needed, if you’re confused or need some help.

Whenever Elim Hawkins uses standard ATC phraseology such as “Go Around,” “Approved,” and “Unable” with non-aviation people, they tend to look at him funny.

Split-Second Confusion

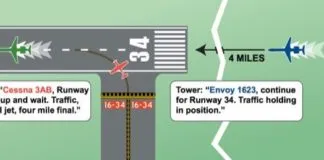

I work a few flight schools on the field, and some of them thought it would be great to have multiple airplanes with very similar callsigns, such as N11234 and N11235. As much as I love working airplanes, having these two in the pattern at the same time has led to more than one “Traffic Alert.”

Some time back, I had one of ’em enter the pattern for touch and goes. A few knocks on wood later, the other also comes in for touch and goes. I decided to put one on the east runway and one on the west to help keep them separate, figuring that if they each had their own runway, the chances of them getting close or confusing their instructions is lower. After being established in their respective downwinds, I advised each, “N11234, use caution, similar sounding callsign, N11235 is also on frequency,” and vice versa to the other. They both respond with “Roger.” Basically, the phrase above means, “pay extra attention for your callsign.”

Wisdom prevailed for a bit until the west-side airplane requested a short approach to a full stop. “Roger, N11234. Short approach approved. Cleared to land [west runway]” I watched both aircraft on their downwinds turn in a short approach as I knew I’d given the short approach only to the west airplane. I let it slide for the moment. I then observed my east-side airplane overshoot his final, heading to the west runway, with the west-side plane just in front. I immediately sent the east plane around and had him make a climbing turn back to his runway. In the mist of all this, the original west-side plane did a full stop and exited the runway.

After the east airplane was established in his downwind, I asked them, “Why did you do that? That clearance was for the other airplane.” They responded with, “We thought it was for us. Sorry.” I kindly replied, “Sir I emphasized the full callsign of the other airplane to avoid this kind of thing. Please be safe.” I’d not had even enough time to spit out a traffic call and they were that close. Be safe out there. —EH

Be advised that going around is advisable in many airplanes that have “landed” but started to porpoise bounce as they typically bounce until the gear collapses. Grummans and Mooneys are prone to porpoising if landed too fast so in that case although the plane may have “landed” it is advisable to go around.

BFR’s are now called “Flight Reviews.”